Does the majority of the public support assisted suicide?

Assisted suicide was on the agenda in Parliament yesterday as MPs debated a motion welcoming the Director of Public Prosecutions' Policy on Assisted Suicide, published in February 2010.

MPs used the opportunity to debate the merits of legalising assisted suicide more generally. The debate was coloured by a claim repeated by four different members.

Richard Ottaway MP: "In 2010, a YouGov poll found that 82% agreed that it is a "sensible and humane approach" not to prosecute someone who helps a close relative "with a clear, settled and informed" wish to die."

Dame Joan Ruddock MP: "[In the said poll] 82% agreed with the compassionate treatment of people as laid out in the DPP's guidelines, only 11% disagreed and 8% said they did not know."

Paul Flynn MP: "Some 80% of people in this country want us to change things."

Heidi Alexander MP: "We know from opinion poll after opinion poll that 80% of the population support assisted dying for terminally ill, mentally competent adults."

But what's the bigger picture?

YouGov 2010

The 82 per cent figure, as mentioned by some of the MPs, comes from the findings of a YouGov poll conducted in late January 2010. It asked:

"The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has signalled that, although assisted suicide remains a criminal offence, he will not prosecute relatives who assist in the suicide of a relative or close friend with a 'clear, settled and informed' wish to die. As long as the law remains unchanged, do you agree with this approach?"

It's important not to miss that the question specifically mentions the law remaining unchanged as a proviso for respondents supporting the statement. However the poll also found the same level support for a change:

"Assisting a suicide is a criminal offence punishable by 14 years in prison. Do you believe the law on assisted suicide should..."

1) Remain as it is - to change it would be to start down a dangerously slippery slope (13 per cent)

2) Be amended to allow some people, such as doctors and/or close relatives to assist a suicide in particular circumstances (75 per cent)

3) Be abolished altogether (7 per cent)

4) Don't know (5 per cent)

Here, a total of 82 per cent of people support either amendment or abolition of the law on assisted suicide. Finally, respondents were asked:

"Do you think doctors should have the legal power to end the life of a terminally ill patient who has given a clear indication of a wish to die?"

67 per cent of respondents agreed that doctors should have this legal right, compared to 21 per cent who opposed it.

ComRes 2010

A further poll was conducted around the same time by ComRes and the BBC. It asked people whether they supported assisted suicide in cases where the person concerned did and did not have a terminal condition.

Interestingly, support for allowing family members to assist without fear of prosecution fell away when the illness or condition was not terminal. 73 per cent supported assisted suicide if the illness was terminal with 24 per cent opposing. If the illness was not terminal, 48 per cent supported it and 49 per cent opposed it.

Support was similar but slightly lower when people were asked about the involvement of medical professionals instead of family members.

Historical trends

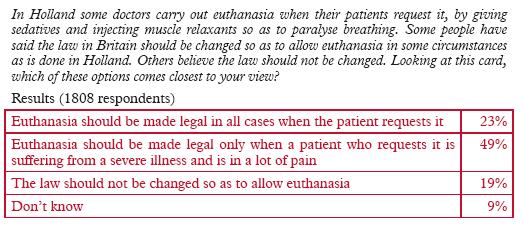

A House of Lords Select Committee report from 2005 discussed public attitudes to euthanasia in detail. The earliest recorded poll is from MORI in 1987, which asked:

The Lords Committee admits these results, taken in isolation, give only a superficial view of public attitudes, but do at least show a convincing majority for some form of change in the law.

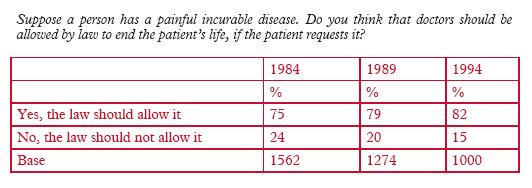

Furthermore, a British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey covering the 1980s and 1990s shows considerable public support for allowing medical professionals the legal right to end a patient's life by request. It also shows increasing support over a decade:

Most interestingly, the BSA survey also reflects some of the nuances of public opinion apparent from looking at the more recent ComRes and YouGov polls. The survey found that support when a person is not expected to recover conciousness but not on a life-support machine falls to 58 per cent, while support for those simply tired of living collapses to 12 per cent.

The Lords Committee report several other polls conducted in the 1990s and 2000s which all show strong public support - none show fewer than two-thirds of people supporting some form of legalisation and most show support in the region of 80 per cent. Thus the report concludes:

"the apparent groundswell in public agreement with the concept of euthanasia registered by the various sources cannot be dismissed and it is evident that there is much sympathy at a personal level for the concept of legally releasing those wishing to die from their pain and those willing to help them from legal consequences."

However, it cautions from the start:

"Very little research exists which is built on techniques appropriate for so complex and sensitive a subject as euthanasia and whether/how it should be legalised. Research sponsors frequently appear to have been more concerned to achieve statistics for media consumption than to work towards achieving a comprehensive understanding of public and health sector attitudes."

Conclusion

One theme evident across all the polls, old and recent, is that a considerable majority of the public support some form of change in the law to allow relatives or medical professionals the right to assist a suicide.

In the more recent polls, evidence suggests that most people do not believe relatives or professionals should face prosecution or legal inhibitions to assist suicides in specific circumstances. Support is reduced when the illness or condition involved is not terminal, and is lower regarding medical professionals' rights compared to relatives' rights.

The evidence also suggests however that this support is not unconditional, and historical polls verify that only a minority of people believe assisted suicide should be given to anyone merely upon request.

In addition, support is not necessarily consistent across different sections of society. Disability charity Scope recently found that most disabled people are concerned about the pressure they may come under if the law were to be relaxed.

However, as the Lords Committee made clear in 2005, all these polls (and, it can be said, the more recent ones) must carry a health warning. The Committee maintains the best measure of public opinion in this case is through deliberation, which can produce informed opinions.

As Full Fact has found with polls on gay marriage, the framing of the questions is also crucial in evaluating how useful the polls are. All the polls shown here use different questions and frame the issues differently. They show a great deal of variance in support when different factors are added, such as a lack of terminal illness or merely rejecting the idea of prosecuting those who assist while keeping the law the same.

So, in short, choose your polls wisely.

UPDATE (30/03/2012)

One of our readers rightly points out that the poll by the disability charity Scope, conducted by ComRes, only measures 'concern' for what a change in the law would imply, and does not provide information to judge whether the respondents actually supported a legal change or not.