Does the UK have the toughest laws on strikes in the developed world?

Jeremy Corbyn claimed in today's Mirror that "Britain already has the most restrictive trade union laws in western Europe".

This is an old article from our archives based on a similar claim a few years ago. It's written a bit differently to how we do things now, and some of the information it's based on is from 2007, so plenty of time for laws in other parts of the world to have changed. Brendan Barber is also no longer General Secretary of the TUC. We've contacted Labour to ask for the source.

We also contacted the TUC to see if it knew of any more recent research on the topic. It pointed us towards the European Committee of Social Rights' conclusion in 2014 that some of the UK's laws on industrial action do not conform with the European Social Charter. The TUC also said the International Labour Organization has stated that the conditions set by the UK with regard to working after strike action presented an obstacle to workers' right to return to work after the strike had ended.

"We have the tightest regulations on strikes anywhere in the advanced industrial world" Brendan Barber, TUC General Secretary

The Independent on Sunday, 4 September 2011.

With the spectre of trade union strikes looming larger as the cuts to public expenditure begin to bite, some on the Government's benches have suggested that the unions' ability to call industrial action should be curtailed.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Quoted in the Independent on Sunday, TUC General Secretary Brendan Barber claimed that this would be "utterly unjustified", arguing that this country already had the strictest system "tightest regulations on strikes anywhere in the advanced industrial world." But is this really so?

Analysis

Tackling this question can seem daunting. How does one go about comparing strike regulations across highly heterogenous legal systems? By what measure should you rank them? How could the TUC back up its claim?

When it comes to UK industrial law, this 50 page document from the Department for Trade and Investment (now known as the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) explains the procedure that needs to be followed in order to call a strike.

In order to legally take strike action a trade union must provide notice to the employer(s) affected, ballot its members and get a majority voting for industrial action. Any action must also be "in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute" (p.6).

The procedural requirements for giving notice and balloting can be broken down in the following way:

-

1st notice

- Must be provided at least 7 days before the expected opening of the ballot.

- Must inform the employer of the planned ballot and its expected opening date

- Must contain: a list of the categories which the employees concerned belong to, a list of the workplaces they work at, the total number of employees concerned, the number in each of the categories and each of the workplaces

Ballot

- If the number of employees involved is greater than 50 an independent scrutineer must be appointed for the ballot.

- It must be a secret ballot

- The voting papers must be sent out by post.

2nd notice

- Must be provided at least 7 days before the date at which workers are expected to take action.

- Must specify whether the action will be continuous or discontinuous.

- Must specify the intended start date of the action.

- Must contain: a list of the categories which the employees concerned belong to, a list of the workplaces they work at, the total number of employees concerned, the number in each of the categories and each of the workplaces

What, however, can be said about how this compares with other advanced industrial countries? A study released by the European Trade Institute (ETI), "Strike Rules in the EU27 and Beyond", provides us with an excellent entry point.

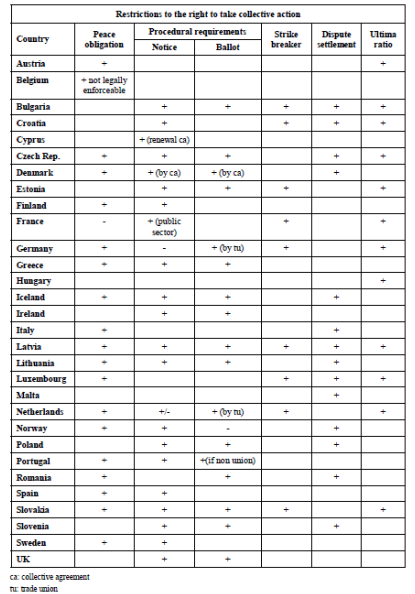

This document analyses the strike laws of the 27 member states of the European Union, as well as those of Croatia, Iceland and Norway. A helpful table is included which lists some of the common types of restrictions on collective action and the countries in which such restrictions are enforced by law.

On top of the requirements of providing notice and holding a ballot, there are four other types of restriction considered:

Dispute Settlement — In some states it is a requirement that the affected parties participate in some sort of dispute settlement procedure. This is not a legal requirement in the UK.

Ultima Ratio — In some states it is a requirement that industrial action is only taken as a last resort. This is not a legal requirement in the UK.

Peace Obligation — In some states further collective action is prohibited during the lifetime of a previously made collective agreement. This is not generally the case in the UK.

Strike breaker — Some states allow employers to hire workers to replace those taking industrial action during a strike. The UK permits strike breaking. (Rather confusingly, in the table, those states that ban strike breaking are marked with a plus symbol).

Depending upon what weighting you put on these restrictions the first three types of requirements will count against Brendan Barber's claim that the UK has "the tightest regulations on strikes anywhere in the advanced industrial world" to varying extents, while the last will count for it.

Returning once more to the issue of "procedural requirements" it does seem that an argument could be made that these are more stringent in the UK than in any other examined European states (that meets Mr Barber's specification of being a member of the advanced industrial world).

Nine of these states (Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia) also require trade unions to both provide notice to the employer and to ballot their members before taking industrial action.

Of these, Denmark, the Netherlands and Slovakia seem to have the most demanding requirements.

Denmark — The strike must be voted for by 75% of those voting at a competent assembly of the trade union. Two notices must be given to the employer; the first, 14 days before the start of collective action; the second, 7 days before the start of collective action.

The Netherlands — The strike normally requires a ballot with a significant majority in favour. There are no exact deadlines for notice but it is assumed that employers will receive a detailed list of demand and a time limit for consent before action is taken.

Slovakia — The strike must be supported by a majority vote in a ballot at which at least half of the affected employees are present. Notice must be given at least 3 days in advance. It must include the starting date of the action, the goal of the action and the names of the leaders of the action.

With its requirements of two notices containing a comparatively large amount of information and a secret postal ballot, UK law seems to be comparable to that of any of these three states. It might be argued that the requirements of larger majorities in the ballot in The Netherlands and Denmark mean that these states have tighter regulations.

The final area to which Full Fact wants to draw attention is that of sympathy striking or solidarity action. This involves workers taking industrial action in support of another set of workers on strike. The ETI report says of solidarity action that it "is by now, in many countries, considered legal under certain conditions, exceptions being Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the UK." This may then be considered another area in which UK regulation is considerably tougher than the European norm.

The report also concludes that the situation in the UK is "very specific in the sense that all collective action is in principle illegal but, since there is provision for immunity in certain defined circumstances, the respective forms of actions have been marked as legal."

Conclusion

A good case can be made that UK strike regulations are among the toughest of European advanced industrial states, especially if one gives particular weight to the burden placed on trade unions by the procedural requirements of giving notice and holding a ballot. However, it has not been established that these regulations are absolutely the toughest in Europe, let alone among all advanced industrial states.

If Brendan Barber and the TUC intend to keep making such a claim they should clarify in which areas they feel the U.K has the toughest regulations as well as the reasons these areas are particularly significant as opposed to those other areas in which other states have clearly stronger requirements.

Correction 14 September 2015

We originally said Brendan Barber was writing in the Independent, when he was just being quoted.

Update 14 September 2015

We added the quote from the ETI report saying that the circumstances of the UK were "very specific". We've also added in a comment before the article starts to make it clear that Brendan Barber is no longer General Secretary of the TUC.