Election claim pitfalls: know what your statistics represent

In our General Election Factcheck 2015 report, we include five common pitfalls when it comes to political claims. These are errors that politicians often fall into, and are all too easy to fall for. We've made these mistakes ourselves at times, and know how hard they can be to spot. Here's our guide to how to identify and avoid them.

Dessert or desert? Words that sound the same can have very different meanings.

Similarly, statistics depend on what exactly they measure. Sometimes they take an immeasurable concept and measure the closest possible thing to it—let's say the notion of social class. Often we talk about income, but for some people it's more than a purely economic distinction. So you can't necessarily take income data and get an easy measure of social class from it.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Sometimes we can get a more precise measure, but what you can conclude from it is quite specific.

Factual claims that sound the same aren't always what they seem. A similar word which may initially sound reasonable sometimes changes the meaning of what gets expressed. We've seen this on several occasions throughout the election campaign.

For example, during the 7-way leaders' debate, David Cameron said: "We have created two million jobs". The two million figure is correct, but there's a difference between saying "two million jobs have been created" and "two million more people in employment".

One person can have more than one job, and one job can be done by two or more people, for instance through job-sharing. These differences sound small, but they're crucial: there are 31 million people in employment, but 33.5 million jobs. If you have the same amount of jobs spread among more people then individually we'd probably be worse off. But if you have more people and more jobs then it's likely we probably are better off.

Positively, Cameron has since referred to "two million more people in work"—that's a much fairer reflection of the figures.

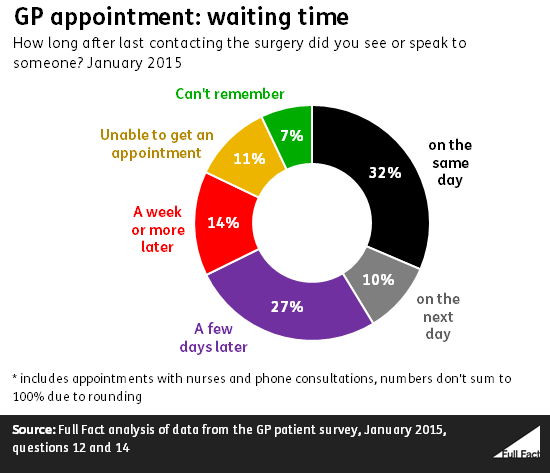

Similarly, confusion was caused when Ed Miliband said in a speech that a quarter of people "can't get an appointment with their GP within a week."

The best figures on GP waiting times show that 11% of patients couldn't get an appointment at all the last time they contacted their GP surgery, while another 14% saw or spoke to someone a week or more later.

So it's fair to say a quarter of patients don't get an appointment within a week. However, that doesn't mean they can't get one. Some people would have been happy to book that far ahead, for instance if they wanted to get a repeat prescription or otherwise if their need for an appointment wasn't urgent.

So a simple change of the word "can't" to "don't" makes this discussion of the figures more accurate. On a positive note, Labour has tweeted that "one in four patients now wait a week or more for a GP appointment". That's a fairer comment.

One other thing to be aware of is whether the figures you're using are for the United Kingdom, or for one of its constituent parts. Often, official statistics across each nation of the UK aren't comparable—which makes factchecking a UK general election tricky.