Donald Trump’s tariffs: what’s happening and what could it mean for the UK?

On 9 April President Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause on higher-rate tariffs levied on imports to the US from more than 50 countries just hours after they took effect, following a week of havoc for global financial markets.

Goods imported from all countries impacted by Mr Trump’s so-called “reciprocal tariffs”, with the exception of China, now face a baseline tariff rate of 10%.

First announced on 2 April—dubbed “Liberation Day” by the Trump administration— baseline 10% tariffs came into force three days later. Higher individual rates of up to 50% took effect on 9 April before being ultimately paused later that day.

The introduction of the new charges had seen the S&P 500 stock index suffer its steepest four days of losses since its creation in the 1950s, while in the UK, the FTSE 100 index fell sharply over the course of the following week.

Following the announcement of the pause, stocks around the world rose dramatically.

The pause will not reduce the level of charge for goods from the UK, which were already generally subject to the baseline 10% tariff. The UK is reportedly hoping to strike a trade deal with the US to mitigate the impact of the tariffs, but Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has said he will only agree to a deal that is in the “national interest”.

Higher tariffs remain in force for some specific products. All foreign-made cars imported into the US have been subject to 25% tariffs since 3 April, while tariffs on steel and aluminium have been at 25% since 12 March.

China continues to be the exception to the tariff rule. On 8 April the US announced tariffs on China would be increased to 104%. The following day China announced retaliatory tariffs of 84%. This in turn led the US to increase the rate for China once again, this time to 145%. In response, China raised its tariffs on US goods to 125%.

This explainer looks at what tariffs are, why they are being introduced in the US and the potential consequences for the UK. It was last updated at 3pm on Thursday 17April and the information below is correct as of then.

With developments unfolding rapidly, we’ll continue to update this article as new information becomes available. If you’ve seen something we should add, spotted a claim for us to fact check or have a question you’d like us to answer, please let us know here.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

The story so far - a quick recap

The President’s latest announcement on tariffs is part of a wider plan, first announced in February, for “restoring fairness in US trade relationships”, which began with the imposition of charges on China, Canada and Mexico. (Mexico and Canada, along with China, continue to be treated differently to other countries—separate tariffs on some imports from Mexico and Canada remain in effect and are currently set at 25%).

On 12 March 25% tariffs on all global steel and aluminum imports came into force. Tariffs on imported vehicles were then announced on 26 March, and these came into effect on 3 April.

Some countries have hit back by introducing or threatening to introduce their own tariffs. The UK has not yet done so in the hope that a wider economic deal that will allow the UK to “avoid the imposition of significant tariffs” can be struck.

On 15 April US Vice President JD Vance said there was a “good chance” of a deal between the UK and the US being reached. The following day White House officials were reported by the Telegraph to have said such a deal could be finalised within weeks.

Despite the pause announced on 9 April, countries around the world are continuing to figure out how to respond to their new trading circumstances. The White House claims that several have signalled a willingness to negotiate with the US, but some were planning to take a harder line prior to the introduction of the 90-day pause.

The EU had announced retaliatory tariffs but has put these on hold for now. It hopes to be able to negotiate a better deal in the interim.

What are tariffs?

Import tariffs are a form of taxes charged on goods imported from other countries.

They can be levied in various different ways, such as by the number, weight or volume of items, but the tariffs announced by Mr Trump so far are ad valorem tariffs, meaning the amount due is calculated as a percentage of the value of the product.

A 10% tariff means an item costing $10 would attract an additional charge of $1.

In addition to being the world’s largest economy, the US is also the leading global importer, pulling in $3.2 trillion worth of goods in 2023. So increasing the cost of selling to the US has the potential to significantly impact the global economy.

Why is President Trump introducing tariffs?

Raising tariffs can be a way of protecting domestic industries, as they make it more expensive to purchase goods manufactured abroad. This prevents local manufacturers from being undercut by imports.

For example, in 2024 the EU imposed duties of between 17% and 35.3% on Chinese-manufactured electric vehicles, amid concerns that European car manufacturers were unable to compete with what the EU described as “unfair” subsidies available to their Chinese counterparts.

This isn’t just about trade though. The White House has also described the introduction of tariffs as “using our leverage to ensure Americans’ safety”—Mr Trump initially said the aim was to to encourage Canada and Mexico to reduce illegal immigration over the US border, and to encourage China to clamp down on the flow of precursor drugs used to manufacture fentanyl.

Who pays tariffs?

Donald Trump has repeatedly suggested that tariffs are paid by foreign countries. During his inauguration speech, for example, he said: “Instead of taxing our citizens to enrich other countries, we will tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens.”

It is actually companies importing the goods into the US that pay the levy though, and the question of where the burden of the tariffs ultimately falls is uncertain.

The companies importing goods may choose to pass the additional costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices. They may choose to absorb the costs themselves, and take lower profits. Or alternatively, it’s possible that foreign manufacturers exporting goods to the US could lower their prices, which would likely impact their profits.

According to Peter Levell, deputy research director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), the evidence from tariff increases under the last Trump administration was that the cost was “almost entirely passed on to domestic consumers”, along with importers.

Speaking in a video interview for the IFS website, he said: “It wasn’t a reduction in the prices that foreigners were charging to enter the US market—it was an increase, almost one for one with the tariff rate, for domestic consumers.”

Tariffs are collected by the customs authority of the country where the goods are being imported into. In the US, they’re paid to the Customs and Border Protection agency at ports of entry across the country, although Mr Trump has directed his cabinet ministers to “investigate the feasibility” of creating an External Revenue Service to collect tariffs. In the UK, tariffs are collected by HM Revenue & Customs.

How have the new tariffs been worked out?

The Office of the United States Trade Representative has published a formula which it says has been used to produce a “tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the US and each of our trading partners”.

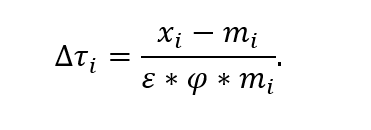

The formula used to calculate what the US calls “an individualized reciprocal higher tariff on the countries with which the United States has the largest trade deficits” looks like this:

The administration has provided a breakdown of what each symbol represents, but simply put, the change in tariff rate has been worked out by taking the US trade deficit in goods with a given country, and dividing that by the value of goods imports to the US from that country. The figure produced by this calculation has then been halved to obtain the new tariff rate for goods imports from that country to the US.

Let’s take the calculation for China as an example. In 2024, the US imported more from China than it exported to China, meaning it had a trade deficit with China. Exports to China were worth $143.5 billion, while Chinese imports to the US were worth $438.9 billion—resulting in a trade deficit of $295.4 billion.

Dividing this trade deficit ($295.4 billion) by the value of imports from China ($438.9 billion) results in a value of 0.67, or 67%. Half of that—33.6%—rounds up to 34%.

On 2 April, President Trump said this value of 67% was the “tariff charged to the USA including currency manipulation and trade barriers”, and that the US would charge “a discounted reciprocal tariff of 34%”. (Though as explained above, this rate has subsequently been increased).

The US tariff rate calculation using the formula above relies on countries having a large trade deficit with the US. The US says that it exports more goods to the UK than it imports, for example, so has a trade surplus in goods with the UK. For countries like this, the White House has applied a 10% baseline tariff. This figure has now been applied to all impacted countries, except China, for 90 days.

There’s been widespread criticism of this formula and the calculations used to support the imposition of the new tariffs, including questioning whether, under this logic, the UK should be subject to any tariffs at all, and noting that it fails to take into account the complex and specific drivers of trade deficits with different countries.

Are the US tariffs ‘reciprocal’?

In early March, Mr Trump announced that the ‘reciprocal tariffs’ being introduced on 2 April would mean: “Whatever they tariff us, other countries, we will tariff them. That’s reciprocal.”

He made similar comments during his so-called ‘Liberation Day’ speech, saying: “Reciprocal. That means they do it to us, and we do it to them.”

However, as the above formula shows, the figures described by President Trump as showing the ‘tariffs’ imposed by other countries are based on broader trade deficit figures, rather than considering specific tariffs, or on other trade barriers which may be levied by individual trading partners on US goods.

Indeed, the US Trade Representative acknowledged this, saying “individually computing the trade deficit effects of tens of thousands of tariff, regulatory, tax and other policies in each country is complex, if not impossible”. It described the formula it has chosen to employ as a proxy for the impact of these factors.

This logic has been widely challenged, including by some of the places targeted by the new tariffs. For example, in a statement on its website, the EU said a single absolute figure for the average tariff on trade between it and the US did not exist, as there were multiple ways the calculation could be done, leading to a variety of results.

It added: “Considering the actual trade in goods between the EU and US, in practice the average tariff rate on both sides is approximately 1%. In 2023, the US collected approximately €7 billion of tariffs on EU exports, and the EU collected approximately €3 billion on US exports.”

In addition, in practice many countries are being charged a rate that is half the level of the average ‘tariff’ they are said to be imposing on the US (which Mr Trump has claimed is a “discounted” rate), while countries with which the US has no deficit, or a deficit smaller than 10%, are still being subjected to a 10% baseline tariff on all imports.

Countries which fall into that category include the UK, Singapore, Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey, Colombia, Argentina, El Salvador, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

The same list also includes Heard Island and McDonald Islands, which form an external territory of Australia, and have no trade with the US whatsoever, as they are inhabited only by penguins. Despite this, a 10% tariff has been imposed. (The US Commerce Secretary has argued this is to close “ridiculous loopholes” and prevent other countries shipping through the islands to reach the US.)

So it’s not the case that the tariffs imposed by the US are “reciprocal”, in the sense of “exactly matched”, to what it claims it is subject to from other countries.

How might the steel and aluminium tariffs impact the UK?

In May 2018, during his first term as president, Mr Trump introduced 25% tariffs for steel and aluminium imports. At the time the move was described by trade body UK Steel as a “hammer blow”.

In March 2022, under President Joe Biden’s administration, the 25% tariff was replaced by a new arrangement which allowed UK companies to export up to 500,000 tonnes of steel and 21,600 tonnes of aluminium to the US tariff-free.

In 2024 the UK exported 180 thousand tonnes of semi-finished and finished steel to the US, worth £370 million. This accounts for 7% of the UK’s total steel exports by volume and 9% by value.

Responding to the announcement of the new 25% tariff on steel and aluminium imports, which has been in force since 12 March, UK Steel director general Gareth Stace said: “President Trump has taken a sledgehammer to free trade with huge ramifications for the steel sector in the UK and across the world. This will not only hinder UK exports to the US, but it will also have hugely distortive effects on international trade flows, adding further import pressure to our own market.”

Mr Stace had previously warned that returning to the 25% tariff would threaten more than £400 million worth of exports.

It’s not yet clear what impact a potential trade deal between the UK and the US could have on these already-implemented tariffs.

How much is UK-US trade worth?

Most British exports to the US are in the form of services, such as finance, insurance and consulting, rather than goods. In 2023, the UK imported £57.4 billion of services from the United States (19.5% of all services imports) and exported £126.3 billion of services (27.0% of all services exports).

That same year the UK imported £57.9 billion of goods from the US, which accounted for 10% of all goods imports, making the US our second largest import partner, behind only Germany. There were £60.4 billion of goods exports to the US, making it our largest export partner, accounting for 15.3% of all goods exports.

The question of whether the UK overall has a trade surplus with the US is a complicated one, because of different sets of data.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports that the UK ran a trade surplus with the US of £71.4 billion in goods and services in 2023. However, according to US figures, the trade surplus was actually in the other direction, with the US reportedly running an overall trade surplus with the UK of $14.5 billion.

The figures differ in part because while the US Bureau of Economic Analysis includes trade with Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man in the UK data, the ONS does not. This allows both countries to report a trade surplus with each other, which means the UK government can use the US figures to argue that no tariffs should be imposed.

Both countries are aware of the discrepancy and are said to be working to harmonise their calculations.