The “Momo challenge” is an online hoax fuelled by media coverage

This past week, the UK media has been filled with chilling reports about the sinister “Momo challenge”: supposedly an “evil suicide game” where a creepy-looking female character appears on children’s screens (messaging them on WhatsApp, or appearing in the middle of seemingly-harmless games or videos) and “challenges” them to commit dangerous acts, including acts of self-harm.

We have seen no clear evidence that anyone has actually been subject to the Momo challenge as described above, either in the UK or abroad. Children’s charities and other experts in the field have described the Momo challenge as a hoax, and several media organisation—including i News, The Guardian, and The Atlantic—have done a good job of debunking it and explaining the background of the story.

Yet while there are now a number of organisations pouring cold water on Momo, the story has had a significant impact on many children and parents.

Media reporting of the supposed Momo challenge has led to police organisations and safety experts publishing advice to parents on the threat posed by Momo and how to avoid it. This in turn has fuelled yet more media coverage.

In response numerous schools have emailed warnings to parents about the supposed threat (Full Fact has reviewed a number of these emails, from both primary and secondary schools). Some schools have even held assemblies to tell their pupils about Momo. One parent told Full Fact that their primary school-age son “had never heard of it [before the assembly] and came home saying that ‘people on the internet were going to try and get him to turn the oven on in the middle of the night’.”

The parent added: “The fact they told the children specific challenges they might be given really worries me—it’s like planting ideas and an excuse for carrying them out.”

Here we’ll draw out the extreme level of media coverage devoted to Momo, in comparison to the dearth of evidence that it actually exists.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Momo returns

This isn’t even the first time the supposed Momo challenge has received coverage in UK news outlets. There was a small flurry of stories about in in August 2018, such as this in the Sun, after a case supposedly linked to Momo in Argentina (from what we’ve seen, concern about Momo appears to have originated in Latin America before spreading internationally).

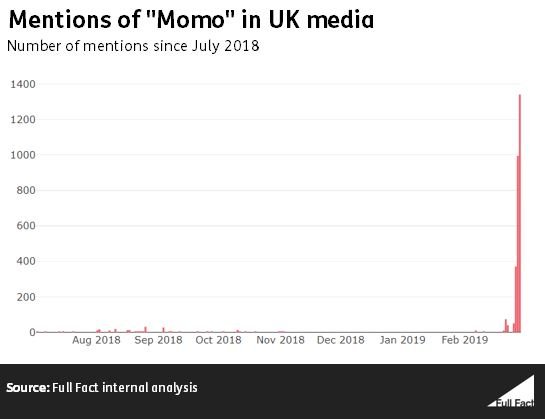

But the small number of stories in August is minimal in comparison to the overwhelming amount of coverage we’ve seen in the past week. This is a chart of individual mentions of “Momo” on UK national media websites since last summer:

The earliest dated report in the recent batch that we’ve identified was from the Manchester Evening News on 20 February, based on a comment made by a mother in a local Facebook group. This was followed up a few hours later by the Mirror.

Articles in other outlets including the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Daily Star followed the next day.

A feedback loop

But the amount of coverage really began spiking dramatically on 26 February, the day after the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) put out a statement warning about Momo:

“This extremely disturbing challenge conceals itself within other harmless looking games or videos played by children and when downloaded, it asks the user to communicate with “Momo” via popular messaging applications such as WhatsApp. It is at this point that children are threatened that they will be cursed or their family will be hurt if they do not self-harm.”

Yet this statement also notes that no official reports have been made to Police, and cites “media reports” as evidence of Momo. A local PSNI force in Craigavon also posted about it on Facebook the day before, saying that the evidence suggested Momo was “run by hackers who are looking for personal info”.

We asked PSNI what prompted them to put out their statement, and if they’re aware of any actual Momo cases, but their response didn’t answer our questions.

National Online Safety (a brand operated by a private company which sells training services to educational establishments) put out a similar warning as a result of “recent reports”. The factsheet—which was subsequently sent out to parents by some schools, according to the emails Full Fact has reviewed—presents Momo as real, saying: “Momo is a sinister ‘challenge’ that has been around for some time… Dubbed the ‘suicide killer game’, Momo… reportedly sends graphic violent images, and asks users to partake in dangerous challenges like waking up at random hours and has even been associated with self-harm”.

This appears to have created a feedback loop. Both PSNI and National Online Safety seem to have largely relied on press reports for their information—but their public comments were then treated by the press as additional confirmation that the claims were true. For example this BBC article, titled “Police advise over ‘freaky Momo game’”, was based on the PSNI Facebook post. Its first sentence states: “Momo may be creepy, but police believe it is clear it is being used by hackers to harvest information.”

The manner in which the BBC shared it on social media would also make you think the Momo challenge was now a confirmed phenomenon: “Hackers are targeting young children on social media through the 'Momo challenge’”.

(The BBC has since updated the piece to emphasise that Momo is a hoax, changing the headline to “Momo challenge: 'Freaky game' described as hoax.”)

Blanket coverage

By midweek, Momo was dominating the UK media. On 27 February, three of the top six most popular UK news stories on Facebook were about Momo. At least seven articles on the topic have gone super-viral, receiving over 100,000 engagements on Facebook in the past week.

Many news outlets have given it blanket coverage. To take one example, at the time of writing the Daily Mirror had at least 30 different articles on the Momo challenge, all dated to the past three days. The most read of these had over 700,000 shares, and most of the articles recycled the same descriptions of the challenge. Several other national news sites have given it similar levels of coverage.

Beyond the sheer number of reports, there is much to suggest that these articles may have contributed to fuelling fear in parents and children that the Momo challenge is a widespread threat.

The Mirror articles include pictures of Momo’s face with underlying text saying “you’re going to die” or “Momo is going to kill you”. To most readers, these images could well look like screengrabs from actual cases of the Momo challenge—but in fact these images seem to come from a months-old YouTube video that simply describes Momo.

Elsewhere, the Mirror reports on a song which parents “need to listen out for”. The Mirror recognises that the song “is likely to be part of the myth surrounding Momo”—rather than a song that has actually been heard as part of the Momo challenge. Yet the Mirror contributes to those myths by reporting that “the audio is said to be that of a traumatised little girl whose parents were mysteriously murdered” and posting the lyrics—which include many repetitions of “Momo. Momo. Momo's going to kill you”—at the bottom of the article.

The reality behind the headlines

As we’ve said, we have seen no firm evidence of any child being subject to the Momo challenge in the manner described (which “sees a shadowy controller send violent images and instructions to a child over social media”, and that they are “threatened if they fail to complete 'orders'”). As with many such panics, however, there are grains of truth that fuel the rumours—and the rumours in turn can lead to aspects of the legend being acted out for real.

For starters, the Momo figure itself is a real object—a statue (named “Mother Bird”) created by Japanese special effects firm Link Factory, and displayed at a Tokyo art gallery.

Additionally, there are a number of videos and images online that refer to the idea of the Momo challenge. And the phenomenon of trolls splicing shock content into cartoon videos and uploading them to YouTube is certainly real, although largely unrelated to Momo (YouTube banned several accounts for this on February 28).

What there isn’t is any firm evidence of the actual challenge itself—children being encouraged to exchange messages with a mysterious figure, who then encourages or threatens them into committing harmful acts.

“Contrary to press reports, we’ve not received any recent evidence of videos showing or promoting the Momo challenge on YouTube,” YouTube said in a statement to BuzzFeed News.

Media reporting repeatedly cites the same few examples of children whose deaths supposedly resulted from the Momo challenge, in Argentina, Russia, or France. In the Argentinian case, “no link was confirmed by the authorities”; the Russian story seems to be a repetition of a previous hoax; and in the French case the boy had researched Momo online but we have not seen any reports that he was actively “challenged” by a Momo character.

Among the tide of Momo-related stories, a few have appeared which describe British children committing acts of harm as a result of Momo.

Yet none of these report any evidence of children having been subject to the Momo challenge through social media or messaging apps—which is how the threat has been reported.

For example, a five year-old girl in Cheltenham cut her own hair and reportedly “keeps talking about Momo”, and an eight-year old boy reportedly showed his mother a picture of Momo and said she had told him to go into the kitchen drawer and take out a knife and put it into his neck.

Additionally there are reports of children either scared of or able to vividly describe Momo in recent days. The extent to which these may have been fuelled by the media coverage itself, or by organic online rumours, is unclear.

There are genuine reasons to be concerned about harms facing young people online (as the recent YouTube story shows), and it’s clearly good for schools and parents to discuss with children how to ensure they have a safer online experience. But it’s not clear that blanket coverage of a spooky story that far outstrips the actual evidence of its existence helps us to do that.