2020, the year QAnon aligned with the UK’s fears

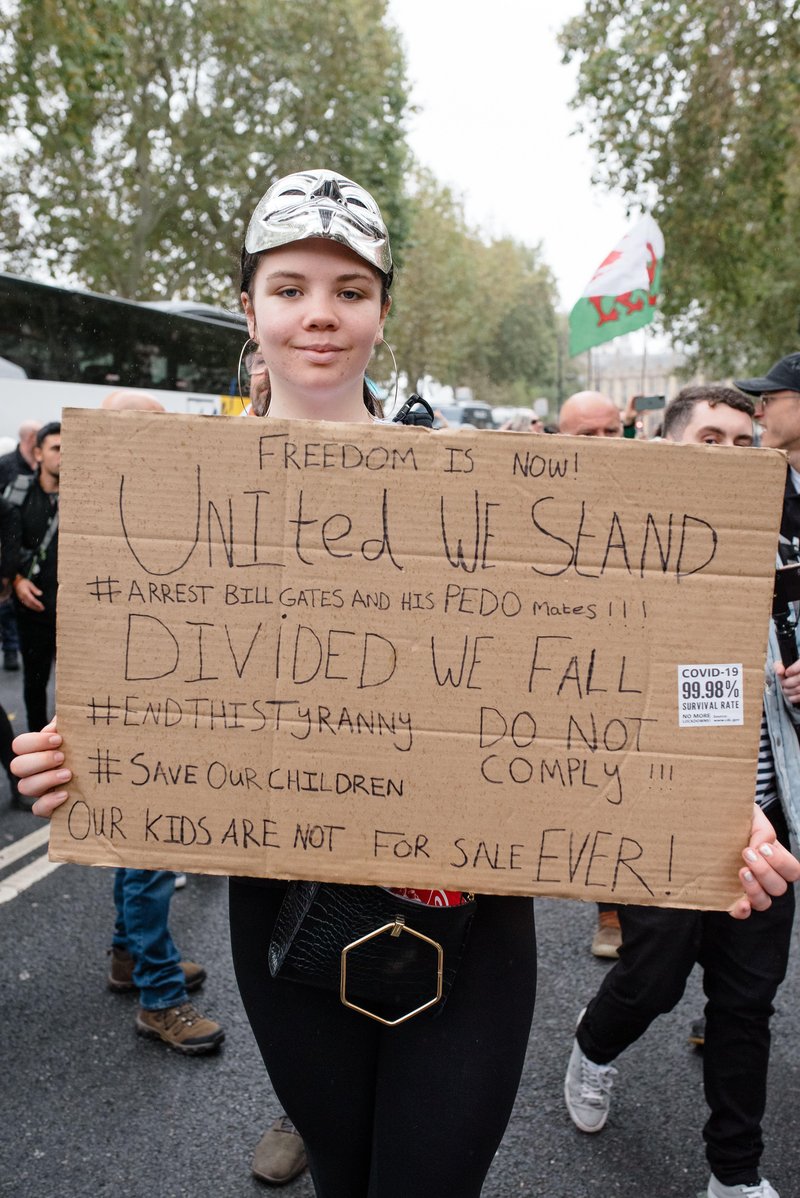

In late Summer of 2020, amidst an ease of lockdown, protesters marched through central London apparently in aid of abused children. The congregation travelled through the city, eventually settling at Buckingham Palace, where, in a now-viral moment, groups yelled “Paedophile” at the royal residence.

You’d be forgiven for not giving this much more thought. In a year where Prince Andrew’s association with convicted sex offender Jeffery Epstein remained at the forefront of conversation, even in a pandemic, protests at Buckingham Palace seem to fit with the public mood.

However, if you had been watching America and its misinformation developments for the previous few years, you may have noticed signs at the march decorated with the letter Q, or shirts emblazoned with the cryptic slogan “WWG1WGA”. You may then have worked out that—whether all the participants fully realised it or not—this march, and many others which have occurred across the UK this year, was rooted in the sprawling US conspiracy theory QAnon.

The theory has its origins in the earlier Pizzagate conspiracy theory—the evidence-free belief that prominent Democrats including Hillary Clinton ran a child abuse ring out of a pizzeria basement, which culminated in a gunman entering and firing into a DC pizza restaurant in December 2016. This and similar beliefs, such as the US being run by “The Deep State”, were often spread by anonymous users on the 4chan message board.

In October 2017, an anonymous user claiming to have “Q” level government clearance posted a message claiming that Hillary Clinton was going to be arrested imminently. Further posts followed, hinting at inside knowledge of a behind-the-scenes battle at the highest levels of government. The posts were often difficult to decipher, have numerous interpretations, frequently made inaccurate predictions, and could have been from anyone.

From these less-than-promising beginnings, QAnon has managed to grow into a vast, interlinked belief system that has acted as an umbrella group for other conspiracy theories. What began with a single narrative—that President Donald Trump was working against a cabal of child-abusing elites— expanded to encompass a litany of pre-existing conspiratorial and anti-authority beliefs: anti-5G, anti-vaccine, and in the midst of the pandemic, anti-mask. “It’s a collective bucket that’s capturing any disgruntled person, more than anything,” says Professor Stephan Lewandowsky from the University of Bristol, who studies how misinformation spreads.

To begin with, QAnon was directly tied to domestic US politics. For its first few years, Q served for some followers as an explanation for President Trump’s often erratic public statements, but it gradually transformed from a message board meme to a political movement, appearing at Trump rallies, and even leading to the election of politicians who seemed to endorse the movement in the US.

But as Hope Not Hate notes, and the intrinsic borderless nature of the internet would suggest, British people have been involved in QAnon since its early inception.

And its “emergence” in the UK this year can be seen as a significant moment, in which the theory mutated and detached from its US political origins. All of a sudden well-meaning, often not “very online” people began replicating deep internet talking points. Across social media, UK-based users began almost unconsciously parroting Q phrases and slogans, while entirely detached from the movement’s US right-wing political roots.

But rather than this being the year that QAnon reached the UK, it could more accurately be said that 2020 was the year that QAnon assimilated with the UK and it’s existing conspiracy theories. And on these shores, feeding on both deep-seated cultural anxieties and our recent history of scandals, it found an almost perfect climate to grow in.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

QAnon in the UK

For all that QAnon is deeply rooted in American political concerns, these don’t seem to be driving its spread in the UK. Financial Times reporter Sid Venkataramakrishnan told Full Fact that, when he attended an anti-lockdown protest in London that featured numerous QAnon references, the content was nonetheless generally disconnected from the theory’s US roots.

“People have Q banners and placards and WWG1WGA t-shirts, and they discuss adrenochrome and child trafficking” but according to one protester, he spoke to “US politics didn't matter at all. What it was about for him was, one, coronavirus being inflated in order to justify lockdowns, and two, the vaccine being pushed out onto the populace, particularly children.”

Annie Kelly, a PhD student and host of QAnon Anonymous says that she similarly saw little to do with Trump, America, or the movement’s MAGA base. She joined the march in August where young women, mothers and children yelled “paedophile” at Buckingham Palace. “It felt very British,” she said.

Others researching QAnon and similar conspiracy theories have said that, in the UK, QAnon has not split down party lines as it did in its emergence in the right-wing politics of the US. Kelly noted one incident which provided clear evidence of this: in the now-removed Facebook group “Freedom For The Children UK” a post by a member about protests directed at Conservative MPs for their vote on free school meals descended into infighting among the group’s members, as people fought over party loyalties, priorities, and causes. Full Fact has likewise found Q-related posts in both pro-Boris Johnson and anti-Conservative Facebook groups, while Tommy Robinson supporters have shared similar content in Telegram.

Kelly also points to the presence of women at these protests as key to understanding Britain’s embrace of QAnon. “It's impossible not to notice that the Facebook groups are dominated by women, especially mothers. As was the protest. It’s impossible not to notice how many young women are involved in this.”

Venkataramakrishnan agrees, and says that the draw of one of the big UK Q-adjacent groups has been its fusion with already popular new-age content: “Laura Ward and her group the Freedom for the Children have a very weird mix of what the witch scene would call a "fluffy bunny" feel: talk of light healers, the power of spirituality (usually through a more religious or New Age lens a than pagan one) and the like.” Venkataramakrishnan pointed to Ward and her group’s collaboration with a spiritualist who does “Clearing Sexual Trauma” ceremonies as an indication of this element of the group’s content. During the writing of this piece, Ward and her group were banned from Facebook as part of a wider crackdown on QAnon content.

This is despite the fact that Ward, as many noted, had been careful in removing instances of overt Q content from her group, aiming for a strand of Q with “semi-respectability”.

So while the Q movement in the UK may have adopted some of the slogans and beliefs from its US origins, the concerns driving it are both more local and more universal. Two broad themes seem to run through the British iteration of QAnon: firstly, a distrust of authority, incorporating both pandemic-related topics like mask refusal or mistaken beliefs about Magna Carta, to more long-standing conspiracy theories like the “New World Order”.

And secondly, it is driven by a fear of harm coming to children. This is overt in posts that express concerns over child trafficking and paedophile rings, and also connects with topics such as vaccine hesitancy, which often focuses on fears around children developing complications from injections. As Venkataramakrishnan says, not everyone who believes in these theories might believe in Q, know the theory’s origins, or really describe themselves as a follower, but it does show an acceptance to Q-esque beliefs.

A deeper history

While Q hashtags and protests give the theory a new, exciting feeling, this sort of moral panic rooted in the fear of harm coming to the children is not new. Samantha North, a PhD student researching conspiracy theories noted the inherent power in the child harm trope: “Who would want to go against ‘save our children’?”

These are deep-rooted fears that have formed the basis of centuries worth of conspiracy theories, from the antisemitic “blood libel” to the “Satanic panic” of the 80s and 90s in the US—both of which are mirrored in QAnon’s belief in Satan-worshipping elites who get high on hormones extracted from children’s blood.

The UK, of course, is not new to conspiracy theories. It's thought antisemitic blood libel claims originate from the murder of a child in 12th-century Norwich. Like much of Europe, Britain was immersed in the witch hunt craze that peaked in in the late 1500s. Today, suspicions range from conspiracies around the death of Princess Diana, are an almost accepted element of British culture, to beliefs spread by figures such as David Icke. These echo in QAnon and may have laid the groundwork for its spread.

And the UK’s embrace of the child protection elements of QAnon cannot be disentangled from Britain’s numerous cases of real-life historic child abuse, many of them high-profile. Child harm and abduction form a central column of British current affairs; just look at the continued fascination with cases such as Madeleine McCann’s disappearance.

North rightly says that conspiracy theories are often rooted in some truth. During the witch trials, the high child mortality rates of the time were one of the things that led people to search for an answer, resulting in beliefs in blood libels, orgies, and child murder. Decades of conspiracies regarding government interference and surveillance are often based on, well, decades of actual government interference and surveillance. Fears of child harm may be universal, but there are good reasons to suspect that the UK may be particularly fertile ground for these kinds of belief.

The culture permeates outside of current affairs. Facebook has always been a hotspot for paedophile hunter pages, and have-a-go-hero-esque posts in which people would accuse people of attempted kidnappings and grooming are common. In late summer and autumn of this year, local Facebook groups across England became overwhelmed with reports of child kidnappings, with many posts using the Q-linked #SaveOurChildren hashtag. The messages read like a concentrated expression of years of conspiracies and fear finally released, now that the topic was in the headlines thanks to QAnon.

So QAnon’s emergence in the UK has really been an amplification of pre-existing conditions that may have made us especially susceptible to its spread. And it also explains some of the aspects that mark the British version of QAnon as different to its US source, such as the prominence of women in the movement.

“It’s not as simple as saying that it's a movement about protecting children and therefore women are interested, I think there’s something going on with QAnon’s unfolding into anti-vax, Covid sceptic groups which are already heavily female, groups with a new age feel,” says Kelly.

In her opinion, “at its heart, the theory is elites are grooming children for these horrific acts, and therefore you have to find all of the evidence for this, and you’re going to look for that in children's content in its media, and mums are the ones who spend the most time with children and their content.”

Is QAnon here to stay?

So is QAnon likely to persist in the UK, and if so, what form will it take?

The imminent end of the Trump administration in the US marks this moment out as a crucial one for whether a movement that exhorted followers to “trust the plan” can survive that plan apparently going off the rails. But the theory's ability to thrive in the UK with little mention of the President suggests it may take more than an election to change things, and that QAnon has the potential to outlive the presidency that spawned it.

History suggests that beliefs like this can be extremely resilient. If we revisit our witch-fearing friends of the 1500s, the decline of witch-hunting and trials by the 18th century could be said to be due to a general change of mood; Professor Alison Rowlands says a rise in legal scepticism of witchcraft from elites made it difficult for the trials to take place. But this did not dispel beliefs of witchcraft among the populace. Accusations of witchcraft continued in the UK up until the late 20th century (and continue in many countries around the world today).

So we may need a level of acceptance that there will always be some, somewhere, who will be drawn to false beliefs born out of fear from the unanswerable questions of the world around them. And long-term change may be driven by external forces as much as the nature of the beliefs themselves—some theorise that the eventual decline of witch hunts was brought on by the end of many of the traumatic events of the early modern period in Europe including the Little Ice Age, and the plague.

But this doesn’t mean that the rise of QAnon is inevitable, or that we are powerless to intervene. For one thing, as already noted, it’s not clear how many of those in the UK spreading Q-related material fully buy into the web of interconnected conspiracies it stems from.

Professor Lewandowsky says that he’s observed that a relatively small number of believers “go deep down the rabbit hole.” “I think depending on how you ask a question you might find a lot of apparent agreement with these theories...There's some data recently in the context of Covid which says somewhere between a quarter and a half of the British public believe in conspiracy theories relating to Covid. But how much do they really believe this? When you get into the nitty gritties, it turns out you can peel away a lot of people who say ‘yeah yeah, it’s a hoax, I don't want to wear a mask, Covid is a hoax’. To me, that's not a really deeply held belief.”

Professor Lewandowsky argues that this large group of believers are the ones who respond to debunking and that the best way to approach this is by warning people what sort of “nonsense” they could encounter online.

“Social media allows that feeling of support no matter how few people believe something,” he says. “If there were no social media, would you find a person who also believes the earth is flat?”

On a similar line, research from First Draft showed that at the beginning of anti-mask protests, a relatively small number of posts online in trending mask hashtags were actually anti. Pro-mask accounts inadvertently boosted relatively sparse anti-mask posts. It’s evidence to suggest that while images of anti-mask protests and other Q-adjacent gatherings may seem worrying, for now, these still remain minority voices.

There may also be hope in understanding that QAnon and similar groups fulfil a need. These spaces also provide people with somewhere to share their fears and be met with a like-minded response. A key feature of conspiracy theories is what people get out of them. Many have argued that QAnon’s cryptic clues can serve as some sort of ultimate brain teaser, with those who correctly link the bizarre ramblings to real-world events seen as intellectually superior. North says that the rise of “armchair activism”, participating in movements through hashtags and likes, has made it easier for people to appear to commit to theories like Q.

Kelly agrees that ultimately, these sorts of theories will recur, as human dissatisfaction is a given. For her, it is not about waiting out our pandemic but removing a little-credited incentive for these groups—sellable products. Just as previous figures like Alex Jones have had a financial incentive to push conspiracy theories in order to drive sales of merchandise, Kelly says that many QAnon pages and devotees leaders have tied financial gain to the movement. Although troubling, this provides a potential course of action for social media companies: demonetise these pages and you may take away the incentive to grow them.

So while those drawn to conspiracism can look to social media to find comforting affirmation of their beliefs, maybe there’s a case for those worried about the rise of QAnon and similar theories to look for comfort in knowing that, while the core fears that fuel such movements may be ever-present in our society, there could be a time where QAnon theories go the way of the witch trials.