Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“...her own party’s education spokesman has admitted that the tuition fees policy has a £100 billion…She has admitted that there is a £100 billion black hole in Labour's student fees policy.”

Damian Green MP, 12 July 2017

In its 2017 manifesto, the Labour party pledged to abolish university tuition fees.

There are two costs potentially associated with this. The first is the cost of scrapping the tuition fees (and associated loans) of future students—this is the policy in Labour’s manifesto. The second is the possibility of wiping off the amounts owed by current graduates—which Labour has separately said it would like to try to do.

It was the latter that Angela Rayner, Labour’s Shadow Education Secretary, was talking about when she referred to a £100 billion cost. When asked on Sunday’s BBC’s Andrew Marr Show how much wiping out current student debt would cost, Angela Rayner said “it’s £100 billion which they estimate currently, which will increase”.

The Student Loans Company has put the outstanding balance due from student loans in England at £89.3 billion (which includes English students studying in the UK, and EU students studying in England). This isn’t just about tuition fee loans—it also includes the cost of maintenance loans. It goes up to £100.5 billion UK wide.

But there are a few reasons to think the cost would not be as high as this—at least when talking about the current amount of student debt (the total amount of debt is increasing each year as more students go to university).

The government already writes off some student loan debt

First, as Ms Rayner said on the programme, the government already ‘writes off’ a certain amount of this anyway due to the way the system is designed.

Graduates only start to repay their debts when they reach a certain income threshold (currently £21,000 for students taking out a loan since 2012) and have their debts written off if they’re not repaid after 30 years (or after 25 years for students who started courses between 2006 and 2012).

So a certain amount is always expected not to be paid back.

The cost would depend on which loans were written off

Second, this £89 billion includes the cost of maintenance loans and tuition fee loans before the higher £9,000 fees came in back in 2012. When discussing the idea, Jeremy Corbyn was talking about alleviating those “that had the historical misfortune to be at university during the £9,000 period”. Some have interpreted this to mean the policy would focus on these graduates.

So if the focus is on wiping off only tuition fee debts for students studying in the £9,000 period, the cost would be lower. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has estimated the outstanding stock of loans for these graduates is roughly £30 billion (but this still excludes the amount of these that are already expected not to be repaid).

Other long-running costs

These costs are separate to the costs of removing future tuition fees, which the IFS has looked into here.

“Youth unemployment is now at historically low levels and lower than many comparable economies”

Damian Green MP, 12 July 2017

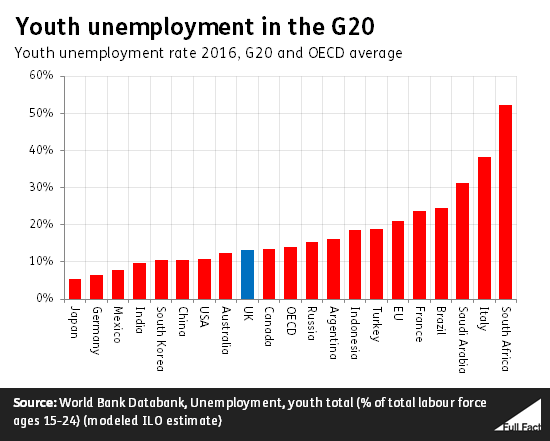

Youth unemployment in the UK is currently 12.5%, the lowest it’s been since 2005 (apart from the beginning of the year, when it was 12.3%). The lowest recorded level since records began was 11.6% in 2001.

This is the proportion of people aged 16-24 who are looking for work, including students who would like to work part-time.

Youth unemployment is still higher than the unemployment rate of older age groups, and has been consistently so.

In 2016 youth unemployment in the UK (classified here as 15-24 year olds) was slightly below the OECD average, at 13% compared to 14%.

That gives us the 9th lowest youth unemployment rate of the G20 economies, and 4th out of countries in the G7 (with Japan up front at 5.4%, Germany next at 6.5%, and the US at 10.9%).

“[Damian Green MP] is the 16th Member to represent his party in Prime Minister’s questions since 1997. Only three of those have been women and the last one before the current Prime Minister was 16 years ago. I believe we have had three women Labour MPs doing this job in the past two years alone.”

Emily Thornberry MP, 12 July 2017

Both the Conservatives and Labour have had three women in total representing their respective parties at Prime Minister’s Questions since 1997 (either as leaders, or as representatives of the leader).

It’s not uncommon for the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition to be absent during Prime Minister’s Questions. When this happens, another senior cabinet member will take the PM's place at the despatch box. Similarly, the leader of the Opposition will be represented by senior shadow cabinet members.

From what we could find, it’s correct that there have been three female MPs representing Labour at PMQs in the last two years. Harriet Harman frequently deputised for Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband, and last took the despatch box in September 2015 as acting leader of the Labour party. Angela Eagle and Emily Thornberry have stepped in for Jeremy Corbyn more recently.

The last three women to represent the Conservatives at PMQs were Gillian Shephard in April 1998, Angela Browning in July 2001, and most recently Theresa May as PM.

These figures don’t tell us how many times each has appeared on the despatch box.

“What assessment have the Government made of the effect on radiotherapy for cancer patients of their decision to withdraw from Euratom…?”

Pat McFadden MP

“... Let me set out the position: the import or export of medical radioactive isotopes is not subject to any Euratom licensing requirements. Euratom places no restrictions on exports to countries outside the EU so after leaving Euratom our ability to access medical isotopes produced in Europe will not be affected.”

Damian Green MP, 12 July 2017

We don’t know exactly how our ability to access nuclear medical materials will be affected if we leave Euratom—a body which regulates and creates a common market for nuclear materials in Europe. To say that access “will not be affected” by leaving—which is the government’s current intention—seems to overstate what we currently know.

There are two key features of Euratom being debated here: the common market it creates in the trade and transport of nuclear materials, and that fact that Euratom has ownership rights over certain sensitive nuclear materials produced by member states—for instance those that could be used to develop nuclear weapons. Some of these materials are subject to special licenses when trading with countries outside the EU (and Euratom can place restrictions on their use), but this doesn’t extend to the medical materials being discussed.

So leaving wouldn’t produce any particular licensing restrictions on medical radioisotopes, but this doesn't mean there will be no issue in accessing them if we leave Euratom. Simply leaving the common market it creates might make it harder for the UK to guarantee a future supply.

Why people are talking about Euratom and medicine

In January this year, the government introduced a bill to give the Prime Minister the power to start Brexit. That became an Act of Parliament, and paved the way for the Prime Minister to formally notify the EU that the UK was leaving in March.

In a footnote to the bill and later the Act, the government said that not only did it intend to withdraw from the EU, it also intended to leave the European Atomic Energy Community—or ‘Euratom’. That’s been followed up in the recent publication of the Brexit 'repeal bill' and a position paper released setting out the UK's aims on nuclear materials and their safeguards.

Euratom creates a single market for nuclear energy in Europe and regulates the movement of certain nuclear materials. It’s not technically part of the EU, but in practice it is intertwined within EU institutions.

That’s caused some disagreement among legal experts over whether the UK can remain in Euratom while leaving the EU. The European Parliament’s chief Brexit negotiator said recently that this wouldn’t be possible. That said, even without full membership, it’s possible that some form of associate membership could be negotiated.

This matters in medicine because some procedures rely on nuclear materials called ‘radioisotopes’ and their related equipment. They’re used, for example, to diagnose or treat different types of cancer. The UK doesn’t have any reactors that produce these, so we have to import them.

There’s a catch too: some of these materials decay very quickly—within hours or days—and can’t be stored. That’s why we work a lot with nearby countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands to bring the materials in quickly, and delays or disruption to this supply can be costly.

There are concerns that leaving Euratom could disrupt the UK’s ability to do this. This came to prominence last week when the London Evening Standard reported that the government faced a rebellion on the plans to leave Euratom from Conservative MPs. In addition, the Royal College of Radiologists expressed concern that leaving Euratom could threaten the supply of vital medical material to the UK.

The government describes these reports as “alarmist”, causing “unnecessary worry” for cancer patients.

Euratom creates a common nuclear market

Euratom creates a nuclear common market—which is similar in concept to the single market. One function of this is it bans member states from imposing customs controls on the imports or exports of certain nuclear products.

One such product covered is what’s called “artificial radioactive isotopes”, which has been interpreted as including the medical radioisotopes we’ve been discussing.

If that is the case, then member states can’t impose controls on the imports or exports of these isotopes.

So if we leave the nuclear common market, it does open up the possibility that additional barriers to trading these products could be introduced, although it’s not clear how likely that would be in practice.

In addition, the UK may find it harder to guarantee the supply of these materials if there are interruptions in supply, according to the Institute for Government. Euratom oversees the supply chain, and it’s not clear what priority the UK would be given if there were a shortage of supplies. Such interruptions have happened before, and might again in the future.

We don’t know that either of these things will happen if the UK leaves Euratom. A lot will depend on whether transitional arrangements are made, and on what kind of relationship the UK strikes with Euratom from the outside, which will be subject to negotiations.

Euratom also owns certain sensitive nuclear materials

The government’s response to these concerns was set out in fuller form yesterday. Rather than look at the consequences of leaving the common market, it makes a separate point that these medical materials aren’t owned by Euratom so there would be no special restrictions on accessing them if we left:

“We do not believe that leaving Euratom will have any adverse effect on the supply of medical radioisotopes. Contrary to what has been in the press, they are not classed as special fissile material and are not subject to nuclear safeguards, so they are not part of the nuclear non-proliferation treaty, which is the driver of our nuclear safeguards regime”

This particular point is right. The treaty establishing Euratom gives it ownership rights over ‘special fissile materials’ produced in the EU. It also has rights over contracts made for trading these materials from inside the EU or outside.

Special fissile materials don’t include the kind of medical radioisotopes we’ve been discussing, and so—as far as we’ve seen—they aren’t subject to the same rules.

Even so, this doesn’t mean leaving the organisation won’t adversely affect the UK’s access in other ways, as we’ve set out above.

---

Thanks to Marcus Shepheard, a researcher at the Institute for Government, for assistance in writing this article.