Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“When she became leader the Prime Minister pledged, and I quote: “I want to make shareholder votes on corporate pay not just advisory but binding” and she put it into her manifesto. That manifesto has now been dumped… She’s gone back on her word.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 6 September 2017

“It’s Conservatives that gave shareholders the power to veto pay policies.”

Theresa May, 6 September 2017

Although it’s not obvious, the two leaders are actually talking about different things. Both have a point—the Conservatives’ latest proposals on executive pay have watered-down those they’ve made in the past but they did strengthen shareholders’ powers in 2013 as part of the Coalition government (and the responsible minister was actually Liberal Democrat).

How are they talking about different things? Because there’s a difference between a “pay policy” and the actual pay that’s set out for directors of a company each year. Theresa May is talking about the rules on setting the policy on directors’ pay for future years, while Jeremy Corbyn is focusing on the amount a director gets in a given year.

Between the Companies Act 2006 and up until 2013, listed companies were required to publish an annual Directors Remuneration Report setting out, among other things, the company’s policy on pay for its directors. Shareholders were able to vote on these reports—but not the actual pay awards to individuals—at Annual General Meetings, but those votes weren’t binding on the companies.

It’s worth saying that even if a vote is legally non-binding, it can still influence the company. Research has shown that in some—but not all—cases since 2003, companies did react when their remuneration report was voted down by shareholders.

In 2013, the Coalition government introduced reforms to make the votes on the setting of future pay policies binding, but kept the actual setting of directors’ pay as an advisory vote.

In the last year Theresa May and the Conservatives have pledged to strengthen this further still, and make setting the pay packages a binding vote by shareholders.

When she launched her campaign to be Conservative leader in 2016 Theresa May said: “I want to make shareholder votes on corporate pay not just advisory but binding.”

The Conservatives’ 2017 manifesto followed that up by pledging: “The next Conservative government will legislate to make executive pay packages subject to strict annual votes by shareholders”.

The latest reforms—announced just last week—amount to a watering-down of this particular pledge. Instead of introducing more binding votes on pay packages, the new requirements will focus instead on greater transparency. Companies with significant shareholder opposition to executive pay packets will be forced to have their names published on a register.

A government official said: “Our response will introduce reforms to make our largest companies more transparent and more accountable to their staff and shareholders and restore the balance between a company’s performance and executive pay”.

“Last week the profit margins of big six energy companies hit their highest ever level.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 6 September 2017

That’s correct if you look at the average.

The average profit margin of the big six energy companies was 4.5% in 2016. That’s the highest since the measure began in 2009.

That’s looking at the profits before tax as a proportion of overall revenue from supplying domestic gas and electricity.

That average hides a lot of variation between companies though. NPower’s supply margin was -6.3%, whilst at the other end of the spectrum Centrica’s was 7.2%.

Looking at the companies individually only two had their highest ever profit margin in 2016 (E.ON and SSE).

“There's already a shortage of 40,000 nurses across the UK.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 6 September 2017

This is correct based on an estimate from the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), though it only refers to England. It found that there were 40,000 vacant nursing positions as of 1 December 2016.

That isn’t the same as the number of nurses NHS England needs, it’s the estimated number of vacant posts they have funding for.

Calculating the number of nursing vacancies

The RCN calculated this figure by asking every NHS Trust in England (barring ambulance trusts) how many full-time equivalent* (FTE) nursing places they had been funded for and how many vacancies they had. 76% of Trusts responded and said that they had around 30,200.

The RCN took that figure and estimated that the overall number would be around 40,000 if all the Trusts had responded.

NHS England doesn’t publish any data on the number of vacancies it has, but it does publish figures that it describes as ‘experimental’ on the number of job adverts it puts out.

There were roughly 11,500 adverts for full-time equivalent nursing and midwifery vacancies in March 2017. That’s 38% of all the vacancies advertised in NHS England that month. (Full-time equivalent in this case is the number of adverts if all the hours available were added up to create full-time jobs).

But NHS Digital—which publishes the figures—points out that one advert can be used to fill multiple jobs or be advertising an ongoing recruitment programme so it’s not possible to get a true sense of the number of vacancies.

For nursing in particular NHS Digital says the level of undercounting is likely to be higher than for other groups of staff because a lot of rolling jobs adverts are used in nursing and advertising overseas which won’t have been counted in the statistics.

What about the rest of the UK?

In Scotland there were roughly 3,200 full-time equivalent (FTE) vacancies in nursing and midwifery in June 2017 (in the NHS). These are actual vacancies counted from the point that the job has been advertised.

In Northern Ireland there were 734 FTE vacancies amongst nurses, midwives and health visitors within Health and Social Care Northern Ireland (the equivalent of the NHS) in March 2015. Of these 596 were fully qualified positions.

These figures don’t look at the same staffing groups so shouldn’t be directly compared.

Information on the number of vacancies in Wales is no longer published.

*FTE is the number of staff there would be if all their hours were added together to create only full-time jobs.

“We have more Nobel Prize winners than any country outside of the United States”

Theresa May, 6 September 2017

Believe it or not, getting the answer isn’t as simple as you might think.

Identifying individual people (or organisations) who have won one of the six Nobel Prizes is straightforward; deciding how to allocate Nobel Prizes to countries is not. Sources differ on how many prizes each country has.

We ran our own calculations using the Nobel Prize data to find out more.

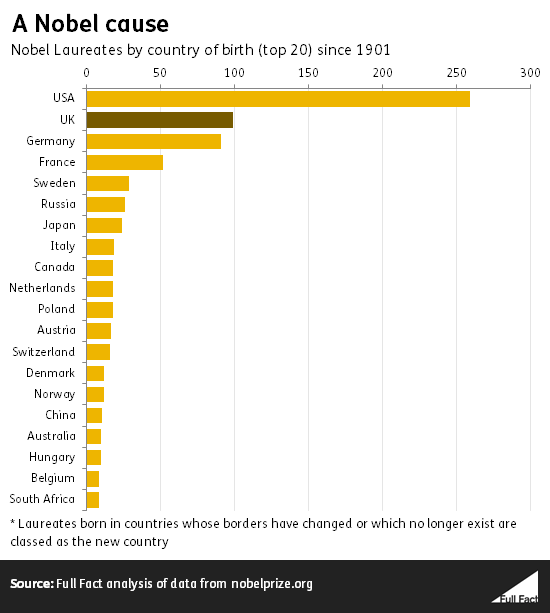

If we base it on the country where each Nobel Prize winner (a "Nobel Laureate") was born then it's correct that the United States has the highest number of Nobel Laureates with 259, followed by the UK with 99. Germany is third with 91 Nobel Laureates.

But there are other ways to add up Nobel Laureates by country

Firstly, countries have changed. India was once part of the British Empire but is now an independent state. Rudyard Kipling, born in India under British rule, won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907—should we count this as a prize for India or the UK?

Second, we might prefer instead to look at which country hosted or funded the work, or the nationality of the Nobel Laureate at the time they were awarded the prize, rather than their country of birth.

Third, a Nobel Prize be may be shared by more than one person. If joint work by a British and a Belgian scientist is awarded a Nobel Prize it might be fairer to say that Britain and Belgium each got half a prize. This happened in 2013 when the Nobel prize for Physics was awarded to Professors Peter Higgs and Englert François, and there are many more examples.

Under this definition, there have been about 61 Nobel Prizes awarded to people born in the UK. This still puts them in second place to the United States’ 139 and ahead of third-placed Germany with just under 60.

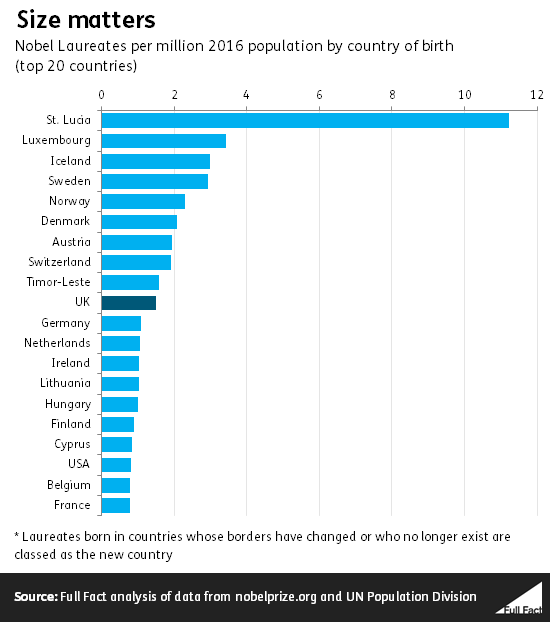

Size matters

Maybe we should also make adjustments so that countries of different sizes are compared fairly. For example Luxembourg has two Nobel Prizes with a population of around 580,000 people. That’s one prize in every 290,000 people. Compare that with the UK, which has one prize in every 663,000 people—which sounds much less impressive.

Looking at prizes per capita the UK comes in at 10th, although this still depends on the factors discussed above. Topping the table is Saint Lucia, which has two Nobel winners from a population of just 178,000.

Other things we might want to consider is the number of universities or the amount of research funding each country provides. If we wanted to be really picky, we could take into account the number of people who were ever citizens of the country since the start of the Nobel Prize awards, rather than just the current population.

But that’s an analysis for another time.