BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“[In] some of our Crown Courts, 50% of the cases are sex cases.”

Liz Truss, 2 March 2017

The Question Time discussion up to this point was about child sexual abuse, but Ms Truss was talking here about sex crimes more generally. She doesn’t appear to be saying that half the criminal cases in some areas involve paedophiles.

We don’t know which specific figures or courts Ms Truss was referring to. We’ve asked the Ministry of Justice.

Official figures can only tell us so much

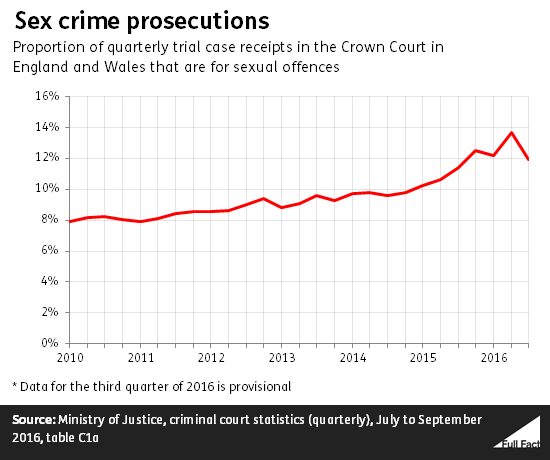

The Crown Court deals with more serious crimes in England and Wales. 13% of the cases received by the Crown Court in the 12 months to September 2016 were prosecutions for sexual offences.

The upshot is that, as far as we know, the official data can’t tell us how many of the defendants that actually face the jury do so because they’re accused of a sexual crime. So Ms Truss may have been using another source of information.

An alternative, unofficial estimate has been made recently

In October 2016, criminal barristers Richard Jory QC and Sam Jones wrote that “more than half of all cases now heard in the Crown Court concern sexual allegations, and the proportion is increasing”. This may be what Ms Truss was referring to.

Mr Jory told us that the barristers spoke “to a number of court staff and users, including other advocates and judges, and combined this with our own experience in the courts to make an assessment”.

On their own, there’s no way to know how accurate the barristers’ overall estimates are without official figures which actually record the subject of trials, which so far we haven’t been able to find.

“The number of police [officers] has dropped, hasn’t it, by 20,000 since 2010.”

David Dimbleby, 2 March 2017

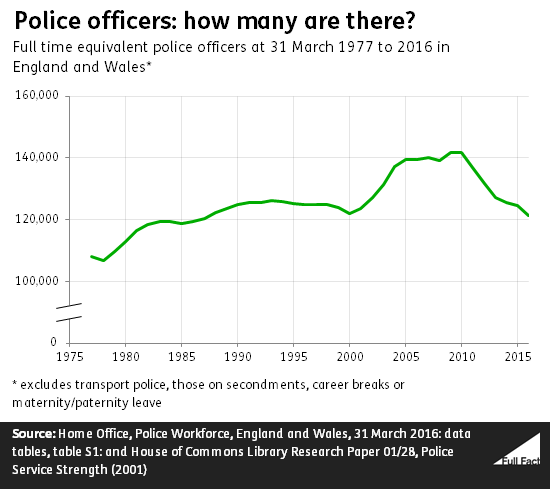

The number of police officers in England and Wales fell by just under 19,000 between September 2010 and September 2016, and just under 21,000 comparing back to March 2010, before the general election that year.

There were almost 123,000 police officers in September last year. Counting those from the British Transport Police and those on secondment it was 126,000.

This relates to the number of full time equivalent officers (or how many there would be if you added up all their hours to make full time roles).

The number of police officers in England and Wales is around the level it was at in 2000 (that’s if we look at how many police officers there were in March last year, which lets us compare further back in time).

Policing is local too, though. If you live in Merseyside, you might not care what’s happening to police numbers in Gwent.

The staffing picture varies across the 43 police forces of England and Wales. The number of officers working for Surrey Police has actually risen by 3%. Every other force has lost officers, with Cleveland seeing the biggest drop (-27%). You can check your area by looking at table A1 of this House of Commons Library research.

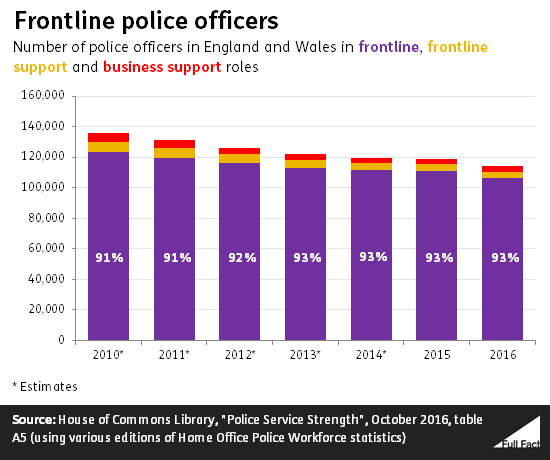

You might also care about the number of frontline officers. There’s no hard and fast notion of who fits that description. The official definition has changed several times. At the moment, officers are categorised as one of frontline (like response teams, neighbourhood policing and front desk roles), frontline support (such as intelligence) and business support (such as training).

Using that breakdown, there are 14% fewer ‘frontline’ officers since 2010. But the proportion of all officers who work on the frontline has risen a little, from 91% to 93%.

Again, that varies. In March 2016, Staffordshire Police had 96% of their officers on the front line, compared to 90% for Greater Manchester.

“Two thirds of police forces were rated good and outstanding, and the reason the Inspectorate gave for the good and outstanding police forces was they did focus more on neighbourhood policing.”

Liz Truss, 2 March 2017

It’s correct that just over two thirds of police forces in England and Wales were rated good or outstanding overall for effectiveness in 2016. These ratings are given by the police watchdog HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) in its most recent report.

Good or outstanding?

Having said that, only one of the 43 forces rated, Durham, was given an ‘outstanding’ rating for effectiveness. The other 28 Ms Truss is talking about were rated ‘good’.

There were also 13 forces rated as ‘requires improvement’ and one that was rated ‘inadequate’, Bedfordshire.

As well as ratings for their effectiveness, police forces are also rated on their efficiency and legitimacy over the course of the year. More forces were rated as good or outstanding overall in these elements in 2016 than for effectiveness.

What did HMIC say about neighbourhood policing?

The most recent HMIC assessment of police forces’ effectiveness focused on four key questions for each. The first of these questions looked at how good the force was at preventing crime, tackling anti-social behaviour and keeping people safe. HMIC told us that neighbourhood policing was mostly, but not entirely, covered by this question.

Other questions looked at how good police were at investigating crime, protecting the vulnerable and tackling serious and organised crime. The ratings each force got for these four individual elements all fed into the overall rating they received. HMIC told us that some elements of neighbourhood policing might also be found in these areas.

On the question of crime prevention 32 forces, or almost three quarters, were rated good (30 forces) or outstanding (two), but that was a deterioration on the previous year’s results. HMIC found “evidence that the service is suffering from the reduction in neighbourhood-based teams. This is a consequence of forces giving priority to addressing vulnerability and risk and on occasion broader budget reductions”.

Across all police forces, HMIC highlighted neighbourhood policing as one of its areas of concern. It said it “found that neighbourhood policing continues to be eroded. The police service is no longer consistently implementing elements of neighbourhood policing known to be effective in preventing and tackling traditional crime and has not yet applied these to 21st century threats (online crime and so-called hidden and complex crimes)”.

It also recommended that there should be national guidelines on what makes for effective neighbourhood policing which all forces should check their performance against.

“We have in Bedford many cases of people who have applied to have residency. They have an 85-page document to fill in. I have friends who have been living in 40 years, married with children, and they have been refused to have a British passport. … the Home Office is making it very, very difficult”

BBC Question Time audience member, 3 March 2017

Citizens of other EU countries have the right to stay in the UK indefinitely if they’ve lived here legally and continuously for five years. They have to meet certain criteria to qualify for this “permanent residence” status, broadly speaking whether they’re working, looking for work, self-employed, studying or self-sufficient.

Citizens of the European Economic Area can apply—using an 85 page document—for a card or document as proof of permanent residence, although at the moment they don’t have to. This can then be used to apply for British citizenship.

Justice Secretary Liz Truss commented on last night’s programme that this process was important so that “we do have proper checks on people who are seeking residency in this country”.

When the UK leaves the EU, ‘permanent residence’ status will no longer apply here unless the government chooses to recognise or replace it. Immigration experts at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory have said that “it is likely to be more difficult (politically and legally) for the government to remove this status from people who already hold it”.

The government has said it wants to reach an agreement to protect the status of EU citizens already living in the UK and those of UK citizens living in other EU countries as soon as possible.

The House of Lord’s recent change to the Brexit bill may require the government to protect the status of EU citizens separate to any guarantee for UK citizens abroad, if this change is also passed by the House of Commons. We don’t know how this registration process would look in practice.

Growing number of EU citizens applying for permanent residence

Since the UK voted to leave the EU, we have seen growing numbers of people applying to get proof of their permanent residence status.

As well as having to fill out long documents, proving eligibility can be complicated for some people. We don’t know the circumstances of the individuals mentioned by the audience member, but the Migration Observatory sets out why individuals might have difficulties.

At the moment, students and those who are self sufficient, such as retired people, have to have “comprehensive sickness insurance”, according to the Observatory. It says there is some uncertainty, even among immigration lawyers, over how to meet this requirement.

Those who are self-employed too may find it tricky to prove their eligibility, depending on whether they have kept several years worth of the relevant paperwork.

Permanent residence as a concept comes from EU law, as opposed to ‘indefinite leave to remain’ which is the route to settlement for non-EU citizens.