BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We have been clearer about having this £100,000 level, which, you know, makes it very clear that people don't have to sell their homes.”

Priti Patel, 18 May 2017

“Well, Priti’s completely wrong … I mean, there is no cap on the amount of money that you have to pay.”

Vince Cable, 18 May 2017

Both panellists seem to be talking past each other, although we don’t know the full details of the new scheme the Conservatives are proposing.

The Conservative Party manifesto released this week outlines three key changes to social care funding in England.

First, people will be eligible for social care funded in part or in full by their council when they have wealth below £100,000. Currently, that cut off point is £23,250.

Second, the value of people’s houses will always be counted towards that figure. At the moment it is not counted for people who receive care in their own homes.

Last, the manifesto says that everybody will be able to pay for social care by having their home sold after they die. Previously, this only applied to people in care homes or nursing homes: it will now extend to people getting care in their own homes as well.

Under the current system, councils can also refuse to offer this provision to people who have more than £23,250 in capital and savings and people whose dependent relatives or spouse rely on the same house. The manifesto does not say whether this will remain the case.

As Priti Patel’s claim implies, nobody will have to sell their homes within their lifetime under the proposed system, although we don’t yet know whether some people will still be ineligible for deferred payment. However, this isn’t due to the £100,000 asset threshold: it’s a separate provision.

Vince Cable is also right that as long as their assets do not deplete to below £100,000, under these proposals there would be no limit to how much people may have to pay for social care. The Coalition government had discussed introducing cap on spending of £72,000, but this was delayed until at least 2020.

UK foreign aid, and an airport that never took off

Update, June 2019: we've written an updated version of this factcheck to reflect the fact that regular commercial flights have since started from St. Helena airport.

“We’re giving this large amount [on foreign aid] away to silly things. We’re even giving St Helena Island £285 million to build an airport that no airlines can take off from.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 18 May 2017

About £285 million was indeed spent on a project to design, build and operate an airport on the island of St Helena for ten years. But as the audience member says, there’s been a snag.

In case you were wondering, Saint Helena is a small island in the South Atlantic Ocean, an Overseas Territory of the UK, with a population of around 4,500 people. The UK government funds the running of the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) St Helena, which is currently the only way to access the island.

The idea behind the airport project is to make the island accessible to tourists, increase investment and boost the island’s population. In the medium term that’s expected to save the UK government money and make it easier for the residents to access good healthcare.

The airport was due to open in May 2016, but the commercial operations were suspended after it was discovered that the wind shear was too severe for commercial planes to land there. These winds were identified by a Met Office report in 2015, and recommendations were made for more equipment near the runway to measure the wind strength.

It’s not completely flightless, though. The airport handled eight flights between May and the end of September 2016, and passenger charter flights to and from South Africa have taken off and landed there this year.

Derek Thomas, a councillor in St Helena, stated that the flights were a “step nearer to commercial use of [the] Airport”.

“It's the actual deprived areas ... that are facing the most significant cuts through council cuts”.

Angela Rayner MP, 18 May 2017

We’ve asked the Labour party if Ms Rayner was referring to council spending on adult social care or council’s overall budgets here. But in either case, there’s evidence that poorer councils are in a worse position compared to more well-off areas.

Reductions in council budgets in England have been larger for “poorer, more grant-dependent councils than their richer neighbours”, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). It says that, overall, councils in England have seen their budgets reduced by an 26% in real-terms between 2009/10 and 2016/17, excluding specific grants for education.

The largest reductions have been in inner-London or in other poor areas throughout England which are more reliant on government grants. On average the 10% of councils who are most grant-reliant had to reduce their spending on services by 33% over this time. The 10% who are least grant-reliant have reduced service spending by around 9% on average.

Ms Rayner seems to have been speaking about adult social care and older people when she made this comment.

The majority of a council’s budget is not ring-fenced so it chooses which services to prioritise and spend its resources on. Council spending on adult social care in England decreased by almost 17% between 2009/10 and 2015/16. But if you include the money they get from the NHS, the decrease is much less—around 6%.

Social care spending hasn’t seen falls as steep as other services. As with overall councils budgets, these spending reductions have been greatest in the areas where “spending, and needs, were previously highest”.

Councils were given powers to raise money specifically for adult social care from council taxes, but the King’s Fund health think tank has said that the poorest councils will be able to raise least, even though they have the greatest need for social care. There has also been more money given to councils from the government specifically for adult social care, though experts have warned that more is needed.

The IFS has said that the money being made available could allow spending on adult social care to return to 2009/10 levels, but it will still be lower per person, because of increases in the population.

“What we are seeing right now through the tuition fees policy is actually it's giving the support to many of those that could not get access to university education, those from disadvantaged backgrounds and they’re the ones we should be targeting and supporting to get into university.”

Priti Patel, 18 May 2017

“But that number's gone down”

Angela Rayner, 18 May 2017

We're focusing here on participation rates in higher education, and looking at what's happening in England, as the two politicians were debating the impact of an increase in tuition fees in England. And we’re using UCAS figures for the number of young people who've been accepted for a place at university, as these are the most up to date numbers.

Looking at other types of students, like mature students or part-time students, may change the picture. For example the overall numbers of mature students has been falling recently.

We’ve asked the Labour party what Ms Rayner was referring to when she said the number had gone down. From the measures we’ve looked at, more disadvantaged students than ever are going to university.

More young people from disadvantaged areas are going to university

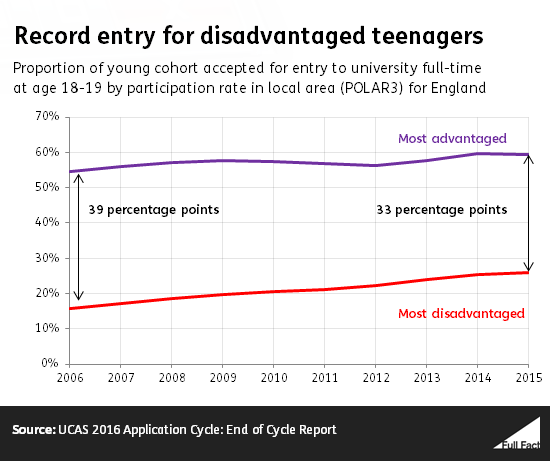

In 2016 the entry rate for 18 year olds living in the most disadvantaged areas increased to the highest on record—19.5% for England.

Disadvantage here is measured according to the rate of participation in higher education by young people in each area, so the most disadvantaged areas are those with the lowest rates of participation by young people.

The rate for those in the most advantaged areas in 2016 increased slightly to 46.3% in England.

The gap between the likelihood of young people from the most disadvantaged areas going to university and those from the most advantaged is narrowing, based on cohort entry rates. These look at how many young people from one year group go to university at age 18 or 19.

Those from the most advantaged areas ae still significantly more likely to go to university though, with the gap in entry rates between the most and the least advantaged areas still at 33 percentage points.

The same is true for young people grouped by a broader measure of disadvantage

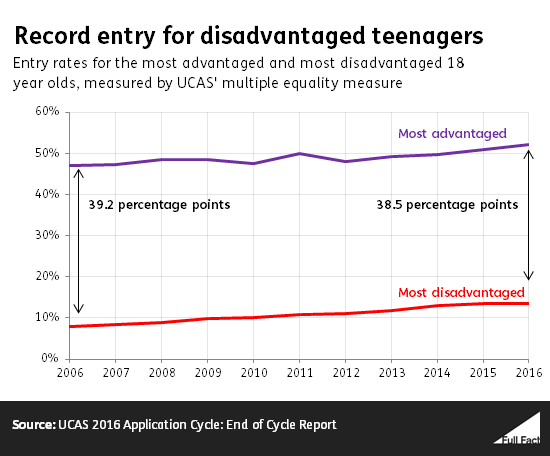

UCAS have released data on a new measure: the ‘multiple equality measure’ (MEM), for the first time for 2016.

This looks at things like a person’s sex, ethnic group, where they live, whether they to a private or state school, and whether they received free school meals—all factors which have traditionally affected whether someone is likely to go to university. Based on a combination of these factors 18 year olds are placed into one of five groups. ‘MEM group 1’ is the most disadvantaged and ‘MEM group 5’ is the most advantage.

On this measure all 5 MEM groups have seen growing participation rates, and reached record highs in 2016.

The most disadvantaged pupils on this measure increased their participation by 5.8 percentage points between 2006 and 2016 (from 7.8% to 13.6%).

This was faster than the growth in participation for the most advantaged group, where participation increased by 5.1 percentage points (47% to 52.1%), but not as fast as those in the middle group (group 3) where participation increased by 8.7 percentage points (from 23.2% to 31.9%).

On the MEM measure the gap between the participation rate of the most and least advantaged pupils decreased slightly between 2006 and 2016 (-0.7 percentage points).

We don’t know for sure how the participation in higher education of disadvantaged groups would change if a policy to scrap tuition fees was adopted.

The IFS has said that, as higher earning graduates currently repay the most of their loans, it is these graduates who would benefit the most from not having to out take a tuition fee loan.

“£6 billion a year is given to buy to let landlords”

Jonathan Bartley, 18 May 2017

The Greens haven’t given us a source for their £6bn figure, but it may be about the tax relief that landlords can claim on their rental income.

Individual landlords don’t have to pay tax on all of the income they get from rent. There are allowances for the cost of running the property - just as self-employed people get tax relief for the cost of running their business.

As much as £14 billion was reportedly claimed in tax relief by landlords in 2012/13, according to a Freedom of Information request to HMRC. About £6 billion of this was relief on ‘financial costs’, including mortgage interest.

But those figures are unlikely to be the same today, because there have been changes to the system in recent years.

In the Summer Budget 2015, the Chancellor announced a series of reforms to landlord tax relief which are now being implemented.

Landlords used to be able to deduct 10% of their rental income from the profit they had to pay tax on, as a ‘wear and tear allowance’. This was abolished in April 2016, although they can still deduct the actual cost of replacing furnishings. And since April 2017, the amount that can be claimed as finance relief (e.g. on mortgage interest) has started to be restricted.