BBC Question Time, factchecked

Question Time this week was in Kilmarnock. On the panel were Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan, former Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale, SNP MSP Jeane Freeman, Guardian columnist Owen Jones and senior editor of the Economist Anne McElvoy.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

“In Britain … 1.4 million women every single year suffer from domestic violence, 400,000 are sexually assaulted, and 90,000 are raped”

Owen Jones, 2 November 2017

Owen Jones’ figures refer to England and Wales, rather than the whole country. They’re imprecise, and it’s important to understand the definitions behind them. But they give a reasonable sense of the scale of each issue, as far as the available figures can tell us.

Domestic violence and abuse in England and Wales

An estimated 1.3 million women aged 16-59 were victims of domestic abuse in England and Wales in 2015/16. Roughly 430,000 cases involved violence. Mr Jones’ 1.4 million figure reflects what the ONS found for domestic abuse in 2013/14.

They estimate that 700,000 men were victims of domestic abuse in 2015/16, of which 230,000 cases involved violence.

Domestic ‘abuse’ and ‘violence’ are terms often used interchangeably, although they sometimes refer to different things. These ONS figures cover everything from physical violence, sexual assault and stalking to emotional and financial abuse.

These figures are higher than the number of cases reported to the police, who recorded around 535,000 domestic abuse-related offences in the year ending September 2017.

Not everyone reports their experience of sexual offences to the police. The Office for National Statistics conducts a Crime Survey which aims to get more accurate figures than the police numbers.

The survey involves face-to-face interviews and asking respondents to complete a self-completion survey. This means the survey may identify victims who have not reported the crime to the police.

Although self-completion leads to “significantly higher” reporting of domestic abuse and sexual offences, it should not be taken as an exact estimate, given that these incidents are notoriously hard to measure.

Sexual assaults and rape in England and Wales

The number of rapes and sexual assaults in England and Wales is also difficult to measure. Again, we need the Crime Survey to help us estimate how many people have been victims of these crimes.

The latest ONS figures estimate that 530,000 women aged 16-59 were victims of sexual assault in the year up to March 2016. They do not publish an exact number for incidents of rape, but they do find that 0.7% of women experienced “Incidents of rape or assault by penetration (including attempts)” in the year to March 2016. That’s seven women out of every thousand.

To get more detailed figures, you need to go back to research from 2013. It found around 2.5% of women said they’d been a victim of an actual or attempted sexual offence in the previous year. That was an average over three years from 2009 to 2012.

The report estimates that around 400,000 women a year were victims of any sexual offence, including attempts. According to the research: “These experiences span the full spectrum of sexual offences, ranging from the most serious offences of rape and sexual assault, to other sexual offences like indecent exposure and unwanted touching.”

Of those, 90,000 were victims of rape, attempted rape and sexual assault offences. An estimated 50,000 women a year were raped, rising to 70,000 including attempted rapes.

The figures are less clear in Scotland

The Scottish Crime and Justice Survey estimates that 3.4% of women were victims of partner abuse in 2014/15, and 1.5% were victims of physical partner abuse. They warn that these figures aren’t accurate for the whole of Scotland, as they exclude people living in institutions and remote islands.

The survey’s definition of domestic abuse excludes all incidents committed by ex-partners or family members.

The Scottish police also record cases of domestic abuse, sexual assaults and rape, although again these will likely underestimate the extents of these issues.

There were 60,000 reported incidents of domestic abuse in Scotland in 2016/17. Of cases in which the gender was known, 80% of victims were women.

There were roughly 4,000 recorded sexual assaults. Almost a thousand of these were against children under 16, who are not covered by the Crime Survey for England and Wales. There were another 2,000 cases of rape and attempted rape. As far as we’ve seen, no gender breakdown is provided for these figures. These figures can’t be compared to the Crime Survey figures for England and Wales.

“I understand why members of my own party have signed that motion, but perhaps they don't know that, as a Scottish Government, we don’t have the powers to recognise anything internationally.”

Jeane Freeman MSP, 2 November 2017

This is correct.

On 30 October a number of MSPs supported a motion in the Scottish Parliament calling on the international community to “recognise the vote of the Catalan Parliament for an Independent Republic of Catalonia”.

Motions in the Scottish Parliament can be used by MSPs to start a debate or “propose a course of action” on a topic.

As a devolved country within the UK the Scottish government and Parliament have powers in a range of different areas. These include things like agriculture, housing and education.

Other powers are “reserved” meaning that only the UK government can legally use them. Any official dealings with countries outside of the UK are included in these reserved powers. So the Scottish government wouldn’t be able to officially recognise Catalonia.

The Scottish Parliament also can’t make any laws about reserved matters and Scottish government ministers can’t act in those areas either.

On 27 October Catalonia declared independence from Spain, the Spanish government then put in place direct rule over the region, dismissed the Catalan government and its Parliament.

In response the Scottish government said “We understand and respect the position of the Catalan Government. While Spain has the right to oppose independence, the people of Catalonia must have the ability to determine their own future.” She also said the EU had a responsibility to encourage dialogue to resolve the situation.

The UK government has said it will not recognise the Catalan declaration of independence and that it was based on an illegal vote.

“For what it's worth, physical correction of children is in decline in almost every Western country, in Scotland and in the rest of the UK.”

Daniel Hannan, 2 November 2017

The research we’ve seen only covers a limited number of rich countries, but the claim is correct as far as this shows. The studies suggest there are some exceptions in other countries, but the general trend is towards less use of physical forms of punishment for children.

Scotland is on the verge of fully banning the smacking of children by their parents, after the Scottish government confirmed it would back a bill proposed recently by an MSP.

This reflects a decline in the use of smacking both in Scotland and several other rich countries, according to a large review commissioned two years ago by NSPCC Scotland. It conceded, though, that the availability of data on the topic was limited.

According to the study: “There is good evidence that in many countries, including Scotland and the rest of the UK, the prevalence of physical punishment is declining and public attitudes have shifted. Physical punishment is becoming less acceptable, and the vast majority of parents express highly ambivalent and negative feelings about its use.”

In Scotland, for instance, several survey findings suggest smacking became less common through the mid-2000s, and found a growing proportion of parents said smacking was either not very or not useful at all.

Across the UK, 61% of young adults in 1998 reported having been smacked on the leg, arm or hand when they were children, compared to 43% saying the same in 2009. There were also falls in smacking on the bottom, being slapped and regular physical punishment.

A separate research paper from 2007 largely agrees, saying: “There is also evidence that parents’ attitudes towards smacking have shifted over time as smacking is less likely to be used/have been used by current parents than by ever parents, and there is often a correlation between parents’ opinions on smacking and their age (with younger parents tending to hold more negative opinions about smacking than older parents).”

The NSPCC Scotland report also looked at other countries. It found—over different time periods—falling trends in the use of physical punishment in Sweden, Germany, the US and Canada. Meanwhile, it didn’t find the same trends in Austria, France or Spain.

“Britain is actually an outlier overall, it’s one of only four countries where it is legal to do this [smack children].”

Owen Jones, 2 November 2017

“The four European countries where it is still legal to smack your child are Italy, Switzerland, the Czech Republic and the UK #bbcqt”

BBC Question Time Twitter, 2 November 2017

The UK is becoming more unusual in not having a ban on parents smacking children, and is one of a small number of EU countries that don’t. That particular list of four countries doesn’t check out.

There's not one UK rule on parents smacking children. The starting point is that it has been legal as “reasonable chastisement” or in Scotland as “justifiable assault”.

The UK government has rejected international calls to ban parents smacking children, and that is what applies in England and Northern Ireland. The Scottish Government is supporting a bill to ban “the physical punishment of children by parents”. The Welsh Government is committed to changing the law too.

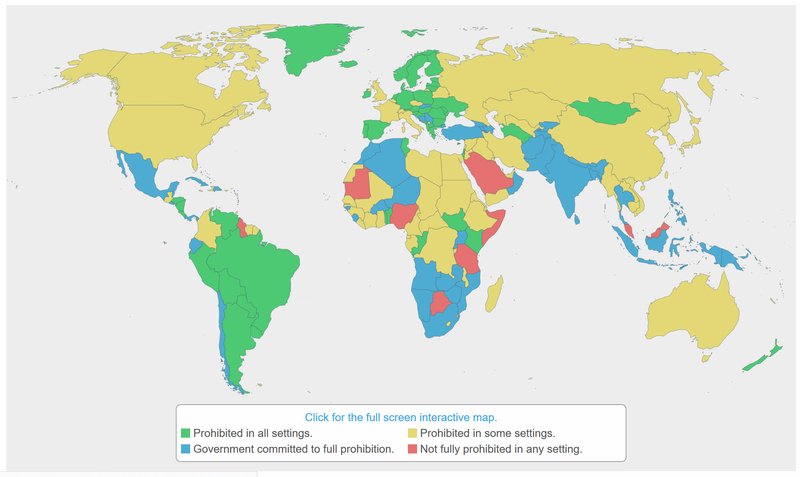

Around the world, opinion seems to be changing fast. 53 states have prohibited corporal punishment of children in all settings, including the home. The governments of at least 55 other states have expressed a commitment to enacting full prohibition.

The Council of Europe says that the banning of corporal punishment of children in all settings has gone from "a minority" of its member countries, to 32 out of 47 now. These member countries range from Andorra to Russia.

The Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children tracks what they describe as progress towards prohibiting all corporal punishment. The have partnered with the Council of Europe to monitor the legal status of corporal punishment in its member countries. The Council says this will support its campaign to persuade all its members to ban it, including in the home. Their research is also relied upon by the NSPCC.

Where in the world is corporal punishment banned?

Of the 28 EU states, the Global Initiative says that Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Italy (debatably) and Slovakia, as well as the UK, do not prohibit parents physically disciplining their children.

Of those neither the UK nor the Czech Republic have any plans for a ban. All the others are in some stage of considering a ban but not necessarily with clear timetables. France even enacted a ban that was overturned for technical reasons by the courts.

In Italy, a 1996 Supreme Court judgment outlawed violence in child-rearing but this has not yet been confirmed through changes in legislation. A complaint that Italy has “no explicit and effective prohibition of all corporal punishment of children in legislation, as well as because Italy has allegedly failed to act with due diligence to eliminate such a punishment in practice” was rejected by the European Committee of Social Rights.

In Switzerland, mentioned by BBC Question Time, a court has ruled against habitual and repeated corporal punishment, but there is no ban.

It’s fair to say that the parts of the UK that are considering a ban on parents smacking children are going with the international flow more than the ones that aren’t.

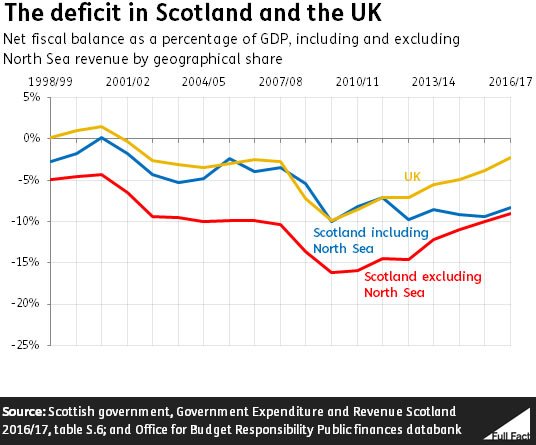

“The short answer to the lady's question really is that the deficit in Scotland is three times, over three times what it is in the UK as a whole, and this has been a high spending country.”

Anne McElvoy, 2 November 2017

As a proportion of GDP the Scottish deficit was more than three times that of the UK as a whole.

The deficit in Scotland was 8% including the North Sea, and excluding it was 9%. This compares to a deficit of 2.3% for the UK as a whole.

Excluding revenue and spending from the North Sea the Scottish deficit has been larger than the UK’s as a proportion of GDP for at least the last 20 years. Including the North Sea the UK and Scottish deficits were last at the same level (7.1%) in 2011/12, but since then the UK deficit has become smaller, while the Scottish deficit has stayed broadly the same.

In monetary terms Scotland had a deficit of around £13 billion in 2016/17. That’s whether or not revenue and spending from the North Sea is included. The UK deficit was larger, at £46 billion.