BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“10,000 people [from the EU] already walked away from the National Health Service, because they don’t feel they’re needed or wanted any more.”

Vince Cable, 21 September 2017

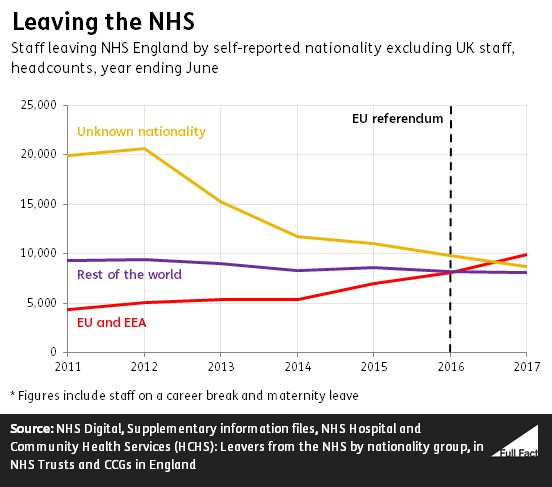

Around 9,800 staff recorded as being from the EU left NHS England between June 2016 and June 2017. That’s around 7% of all staff leaving in that year.

These figures are at record levels in recent years, as are the levels of staff from the UK leaving the NHS. But these levels were also increasing before the referendum.

None of these figures tell us whether the staff left the country or not, or whether their reason for leaving was in any way connected to the EU referendum result.

There’s actually more to these figures than meets the eye.

The information about where a staff member is from is self-reported—meaning that it could refer to their country of birth, their citizenship or their cultural heritage. NHS Digital, which publish the figures, also points out that the number of staff of “unknown nationality” leaving the NHS has decreased. As more people provide their nationality, it will increase the numbers in the other “known nationality” groups.

These figures don’t just include staff who leave the NHS permanently, they also count staff going on a career break or on maternity leave. We’ve asked NHS Digital what proportion of “leavers” this would apply to.

Why are staff leaving?

We don’t know why the 10,000 staff covered above left. But separate figures, looking at 5,700 NHS staff from the EU who left NHS England between June 2016 and March this year, examined why they had left. Again these figures include staff who may not have left permanently.

About 30% of staff had an unknown reason for leaving. Another 24% resigned their post voluntarily because they “relocated”, 12% resigned voluntarily for “other” reasons and 9% left because their fixed term contract had ended.

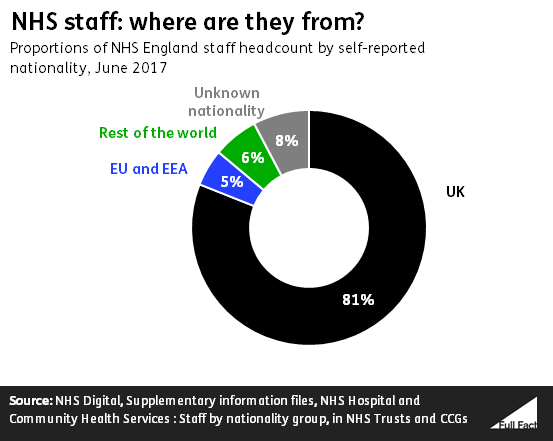

While the number of EU staff leaving the NHS has increased over the last few years, the number of EU staff working in the NHS has continued to increase. There were about 61,600 staff who said they were from the EU working in NHS England in June 2017.

These figures don’t include GPs and other staff working in GP practices.

“We’ve seen, statistics have shown, that the higher tuition fees haven’t really put people, students from disadvantaged backgrounds, [off] from going into university either.”

Dia Chakravarty, 21 September 2017

The 2012 increase in tuition fees doesn’t seem to have affected the long-term trend of growing proportions of young people—including from disadvantaged backgrounds—applying or going to university. It is harder to say what the impact is for mature students—the Office for Fair Access says that the evidence is mixed.

Looking at several different measures, the proportion of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds applying and going to university in England is at a record high. Some of these measures do show a slightly slower increase in the past year or two. We’ve got more detail on this and other areas of the UK in this article.

There was a dip in numbers immediately after the 2012 fee increase, but numbers have since returned to record levels.

We can’t know what the numbers would have been if tuition fees hadn’t been increased.

“He [Jeremy Corbyn] said he’d abolish student debt … he’d abolish the whole thing … He said he would deal with it … he misled people.”

Kwasi Kwarteng, 21 September 2017

“He actually didn’t, Kwasi … He didn’t say it.”

Jess Phillips, 21 September 2017

“You are lying to me and the British people.”

Paul Mason, 21 September 2017

Jeremy Corbyn didn’t commit to abolishing student debt before the last election, although he did say he would “deal with” the high debts of graduates and was looking at ways to do so.

The official Labour policy for existing graduates was that they would be protected from above inflation interest rate rises on existing debt and Labour would “look for ways to ameliorate this debt burden in future.” This policy was not mentioned in the party’s manifesto.

Mr Corbyn did say in an interview with NME magazine a week before the 2017 general election that he was “looking at” ways to reduce, ameliorate, or lengthen the period of time that “those that currently have a massive debt” have to pay it off. He also said he didn’t “have a simple answer for it at this stage”.

Those who didn’t see the detail of Mr Corbyn’s comments may have got a stronger impression from some of the wider news headlines. The Times reported “Labour promises to write off graduate debt”, and iNews reported “Jeremy Corbyn: Labour will write off graduate debt”—specifying in the detail of the article that it was something Mr Corbyn had “suggested”.

Other Labour figures during the election campaign did hint that abolishing—as opposed to reducing—debt was the policy.

What Jeremy Corbyn said

During the interview Mr Corbyn is quoted as saying:

“First of all, we want to get rid of student fees altogether ...

“We’ll do it as soon as we get in, and we’ll then introduce legislation to ensure that any student going from the 2017-18 academic year will not pay fees. They will pay them, but we’ll rebate them when we’ve got the legislation through – that’s fundamentally the principle behind it.

“Yes, there is a block of those that currently have a massive debt, and I’m looking at ways that we could reduce that, ameliorate that, lengthen the period of paying it off, or some other means of reducing that debt burden ...

“I don’t have the simple answer for it at this stage – I don’t think anybody would expect me to, because this election was called unexpectedly; we had two weeks to prepare all of this – but I’m very well aware of that problem ...

“And I don’t see why those that had the historical misfortune to be at university during the £9,000 period should be burdened excessively compared to those that went before or those that come after. I will deal with it.”

Some Labour figures have sown confusion about the policy

Both Jeremy Corbyn and the Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, said in interviews after the election that abolishing student debt was never promised, but that it was a “real ambition”. The Shadow Education Secretary, Angela Rayner, also told MPs that this was never the promise.

During the election, however, some Labour figures seemed to have sown confusion about the policy.

Labour’s shadow justice minister Imran Hussain said in a video that “every existing student will have all their debts wiped off”. Another shadow minister, Sharon Hodgson, tweeted that “Labour could write off historic student debts| All those in early 20's with student debt”.

The first doesn’t say that graduates would also have their debts wiped off, and the second doesn’t say the pledge is a certainty. Nevertheless, compared to Mr Corbyn’s “looking at ways that we could reduce that, ameliorate that, lengthen the period of paying it off, or some other means of reducing that debt burden”, both interventions could have given voters the wrong idea about what was being promised.

“Quite apart from the actual [Brexit] divorce bill, 10,000 jobs have already moved out of the financial services sector.”

Vince Cable, 21 September 2017

This is not what the source of the figure says. The 10,000 jobs figure is based on predictions for future jobs moving out of the UK, and on a particular model of Brexit that isn’t yet certain. There is no evidence that 10,000 jobs have already been removed from the financial services sector since the Brexit vote.

So where did the figure come from?

The Liberal Democrats told us that Mr Cable was referring to an article published in the Evening Standard. The Standard, in turn, said that Miles Celic, chief executive of TheCityUK—the representative body for the financial and professional services industry—“confirmed estimates that 10,000 jobs have already gone” since Brexit.

TheCityUK told us that Mr Celic discussed this figure on the Today Programme last week. During the programme presenter Dominic O’Connell said the latest estimate from Reuters was that 10,000 people had left the financial services sector since the referendum.

This is incorrect—the Reuters figure is a prediction of the number of jobs the sector might be lost or move overseas in future if the UK leaves the single market.

Mr Celic was then asked if the 10,000 figure sounded correct: he responded it didn’t feel “in the wrong ballpark” because TheCityUK had commissioned independent analysis in 2016 that suggested at least 35,000 jobs could be lost as a result of Brexit.

The source of the 10,000 figure makes no claim about how many jobs have gone since Brexit

The recent Reuters survey of leading financial service companies based in the UK suggests that around 10,000 jobs in finance could be moved from the UK or created overseas if the UK no longer has access to the single market after Brexit.

These aren’t jobs that have already moved out—in fact there’s no specific time period provided for when these jobs will be lost by.

Separate ONS figures also show that the number of jobs in financial service activities in June 2017 was at a similar level to June 2016, when the Brexit vote occurred. Even though these figures don’t tell us what causes changes in job numbers, there’s little evidence yet for the large job reductions suggested by the 10,000 figure.

A recent survey of businesses can’t give us a definitive picture of future job losses

The survey itself also has limitations—it can’t give us a definitive prediction of what will happen to finance jobs during and after Brexit.

The survey, carried out in recent months, spoke to 123 of “the largest and most internationally focused financial firms in Britain”. Only 39 companies employing around 350,000 people actually gave responses on their staffing plans. No information was provided by some of the biggest employers in the sector, including Bank of America and Credit Suisse.

This could suggest that the figure may be much higher if all firms were interviewed, but the picture could also be affected by the type of Brexit which ultimately occurs.

It depends on the kind of Brexit deal that is reached

The key question here is whether the UK retains access to the single market, and therefore banks based there are able to carry on “passporting”. This means that a firm authorised in one EEA member state can “carry on permitted activities in any other EEA state”.

The survey found that many British and American banks currently use London as their passporting base, and so British withdrawal from the single market would require moving jobs out of the UK in order to establish an “EU hub” elsewhere.

The uncertainty over the shape of Brexit means that many survey respondents said they were choosing to operate a “two-stage contingency plan”. This broadly means moving “small numbers to make sure the requisite licenses and infrastructure are in place”, before taking a final decision on how many jobs to move once the Brexit picture is clearer.

Uncertainty could also be stalling banks’ action on jobs

Two reports by the firm Oliver Wyman predict a much higher level of potential banking job losses. One from 2016 predicted up to 35,000 finance jobs could be lost in a "hard Brexit" scenario, with the figure rising to as much as 75,000 once “additional activities” related to the finance sector, such as insurance, were factored in.

Another report from the same firm in 2017 similarly predicted up to 40,000 finance job losses, without specifying how many extra could be lost due to "additional activities".

The 2017 report also finds that uncertainty over the shape of Brexit is limiting banks’ current action. It found that many banks are currently focused on the low-cost move of applying for licenses in other EU jurisdictions, rather than making firm decisions on moving jobs.

So in any case, it’s too early to judge what banks’ response to Brexit will be in terms of jobs moving abroad.