BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time this week was in Bury St Edmunds. On the panel were secretary of state for culture, media and sport Matt Hancock MP, shadow home secretary Diane Abbott MP, co-leader of Green Party Caroline Lucas MP, human rights lawyer Jen Robinson, and comedian Simon Evans. We factchecked claims on immigration rules, Windrush, and Asian economies.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“In 2014 when Theresa May was home secretary she changed the law to remove the protection from Commonwealth citizens, and I voted against that.”

Diane Abbott MP, 26 April 2018

Diane Abbott’s office was not immediately able to say which vote she was referring to but she voted seven times on the Immigration Bill in 2014. Six of those votes were on other specific issues. One was voting against the whole Bill.

During that debate Diane Abbott asked Theresa May, then Home Secretary and the Minister in charge of the Bill, this question: “has she given no thought to the effect that her measures that are designed to crack down on illegal immigrants could have on people who are British nationals, but appear as if they might be immigrants?”

Theresa May’s reply started: “We have given a great deal of thought to the way in which our measures will operate.” She did not mention British nationals specifically and concentrates on the complexity of the system the Bill was designed to change.

The Commonwealth, the Caribbean, or the Windrush generation were not mentioned specifically in this debate.

The British Nationality Act 1948 made citizens of Commonwealth countries citizens of the UK and Colonies. The Immigration Act 1971 changed the law to grant only temporary residence to most new arrivals, but still allowed people who'd arrived before 1973 to remain in the UK indefinitely.

The practical effect of the change in the Immigration Act 2014 is disputed. The government says it didn’t remove protection. In a recent debate the current Home Secretary Amber Rudd said that the exemption from deportation for commonwealth citizens was taken out “because it was not necessary; those people had the rights under the 1971 legislation.” The problem, she argued, was “the information to confirm” that people had those rights.

"Theresa May knew [about the Windrush issue] in 2014 - there was a Legal Action Group report in 2014 which reported on all these stories."

Jen Robinson, 26 April 2018

In 2014 the Legal Action Group, a charity which describes itself as promoting equal access to justice, published a report called ‘Chasing Status: The ‘Surprised Brits’ who find they are living with irregular immigration status’.

They told the stories of long-term UK residents unable to prove their immigration status who then had problems accessing benefits, work and facing removal from the country.

While the report doesn’t explicitly talk about the ‘Windrush generation’ it includes the stories of four people who came from Commonwealth countries before 1973, and so have the right to live indefinitely in the UK under the 1971 Immigration Act.

These people faced including losing their job, receiving orders from the, then-called, Border Agency to leave the country, being unable to use the Job Centre and losing benefits.

After publication, the report was covered in the Guardian who received the following response from a Home Office spokesperson:

"The Home Office said it worked closely with local authorities and other groups to ensure that people with an “uncertain immigration status” received appropriate support in this “complex area of work”.

“When these people are brought to our attention we will consider their immigration status,” said a spokesman. “However, it is up to anyone who does not have an established immigration status to regularise their position, however long they have been here. All applications are considered in line with the immigration rules and nationality legislation, taking account of any compelling or compassionate circumstances.””

We don’t know whether Theresa May, then Home Secretary, saw the report first-hand.

“One of the very unfair things about our current system is, for example, if you want to marry and bring in someone from a country outside of the EU, you have to have a salary of over £18,600…. 47% of the population are not going to earn enough money to be able to bring in a wife or a husband from a country outside of the EU.”

Caroline Lucas MP, 26 April 2018

In July 2012, the government introduced a minimum income requirement for people applying to bring a partner living outside the European Economic Area (EEA) to the UK. That was set at £18,600 a year before tax, and remains at this level today.

This threshold doesn't apply to EEA citizens who want to bring a non-EEA partner to the UK.

If applicants have children, the income required rises by £3,800 for the first child and £2,400 for each child after that. Their partner’s income can sometimes count towards the threshold, if they are already working in the UK on another visa.

£18,600 was chosen following analysis from the Migration Advisory Committee—which advises the government on immigration policy. The government asked it what the income threshold should be to ensure spouses and children brought to the UK wouldn’t become “a burden on the state” financially. As experts at the Migration Observatory explain:

“The £18,600 threshold is the level at which a specific type of family – a single-earner household with no children paying £100 per week in rent – is no longer eligible for tax credits or housing benefit.”

We don’t know the exact number of people who haven’t come to the UK because of the threshold.

47% is an old estimate—it refers to the estimated proportion of British nationals working as employees who earned below £18,600 around the time the threshold was introduced, and was widely reported at the time.

Since earnings have been increasing and the threshold has stayed the same, the proportion of workers earning less has fallen. It was estimated at 43% in 2014 and 41% in 2015, which are the most recent estimates we’ve seen.

This is the percentage of British nationals only. The earnings threshold also applies to non-British nationals who are settled in the UK, or living here with refugee leave or humanitarian protection.

A single, national number for this also doesn’t tell the whole story, because incomes vary a great deal. The Migration Observatory has previously identified that women, ethnic minorities, younger people and people living outside of London and the South East are less likely to be eligible on income grounds.

“The reason that I think we should leave the customs union is because I want to have essentially free trade with Europe but also free trade with the rest of the world, with America which is growing fast, with the Far East which is going gangbusters at the moment”

Matt Hancock MP, 26 April 2018

Outside of the customs union, trade with the EU won’t be quite as “free” as it is now. We could have a free trade agreement with Europe that removes tariffs but, unless we’re inside the customs union, goods imported into the EU will need to provide proof of where and how they were made.

Leaving the customs union would allow us to agree our own free trade deals with other countries (you can’t do this as a customs union member). By leaving, we would no longer be a part of existing EU trade deals with other countries, and would face tariffs on trade with other countries until free trade agreements were made.

Economic growth in other regions

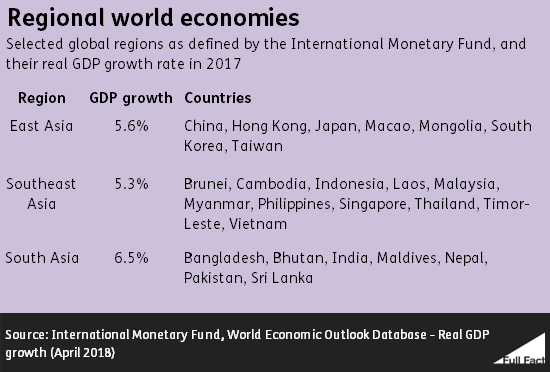

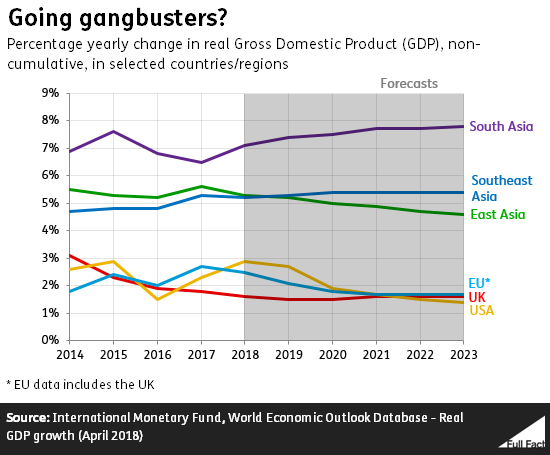

In 2017, the UK’s GDP grew by 1.8% in real terms compared to 2.3% in the USA, 5.6% in East Asia, 5.3% in Southeast Asia, and 2.7% in the EU. That’s according to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The fastest growing region worldwide (as defined by the IMF) last year was South Asia, with real GDP growth of 6.5%.

The IMF forecasts that these growth rates will stay quite stable over the next few years—although they expect the EU, USA, and East Asia to slow slightly, and South Asia to pick up further.

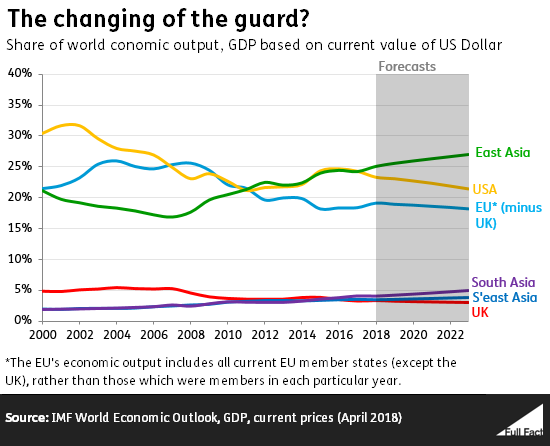

How much is each economy worth?

In 2017, the USA made up 24% of the world economy, the EU made up 21% (or 18% without the UK), East Asia made up 24%, Southeast Asia made up 3%, and South Asia made up 4%. That’s basing the value of each region’s economy on the current value of the US dollar.