BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Dumfries this week. The panelists were: Conservative peer and former secretary of state for Scotland Michael Forsyth, the Labour MP Chris Williamson, the SNP's minister for culture Fiona Hyslop MSP, co-convenor of the Scottish Greens Maggie Chapman and Daily Mail journalist and commentator Peter Oborne.

This week's Question Time contained some complicated claims which we are working to factcheck and will publish soon. In the meantime here are some of the main claims from the show which we factchecked on: spending on Scottish public services and the NHS in Scotland, who owns Britain's trains, energy and postal service, and junior doctors obtaining UK visas.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We have regularly increased investment in the Health Service since the Scottish Government came to power. Investment in the Health Service has gone up £4 billion to £13 billion.”

Fiona Hyslop MSP, 25 January 2018

The Scottish government told us that Ms Hyslop was referring to the increase in health spending in Scotland since the year before the first SNP minority government came to power in 2007.

At that time day-to-day spending on health was budgeted at just under £9.1 billion. In 2018/19 it is budgeted to be over £13.1 billion. That’s a difference of about £4 billion, but these figures don’t account for projected inflation over that time.

If you factor that in then the difference is half that at £2 billion.

That spending hasn’t happened yet. These figures are projections for future spending. Spending for this year suggests the increase since 2006/07 is slightly less than £2 billion so far.

Health is a devolved area in Scotland, and the Scottish government decides exactly how much money is going to go into the NHS budget each year.

The Scottish government’s budget is made up of three components: money it receives through the block grant from the UK government, money raised through taxes in Scotland (and collected by the Scottish government directly), and money raised through borrowing.

“You’ve got 20% more per head because of the money that comes from England under the Barnett formula.”

Michael Forsyth, 25 January 2018

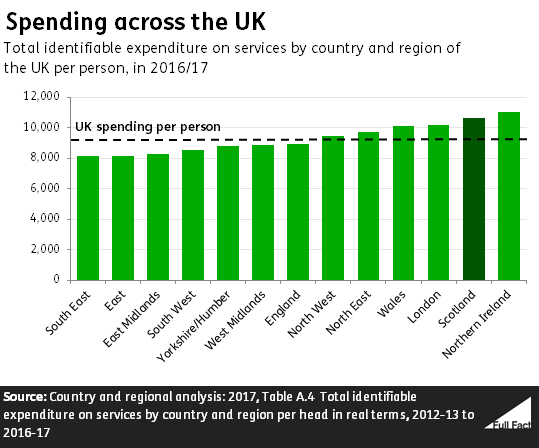

It’s correct that, per head of the population, around 20% more is spent on public services in Scotland, compared to England. But this money comes from the block grant from the UK Treasury, rather than from England specifically. An increasing proportion of the Scottish government’s budget also comes from taxes it raises.

In Scotland, just under £11,000 was spent per person in 2016/17 and in England it was just under £9,000.

This uses a measure of spending called ‘identifiable expenditure’, which is money that the government can say was definitely spent in that region or country. This includes all kinds of services, from health to transport, and covers money spent by the UK and devolved governments as well as local councils and public corporations.

It doesn’t look at the ‘non-identifiable spending’, which is spending that can’t be associated with one part of the UK in particular, like national defence.

The Scottish government says there are a number of reasons why spending in Scotland is higher.

For example, people live further apart in Scotland—the population density is lower—so services cost more to provide.

Also, the spending needs of each country aren’t the same. Some services like water and sewage are in the public sector in Scotland whereas in the rest of the UK they’re in the private sector. There’s also a greater need for health and housing services than the rest of the UK.

We’ve looked at all this in more detail here.

The Scottish government’s budget

Scotland, along with the other devolved countries of the UK, receives a block grant from the UK government. This amounted to around £25 billion in 2016/17 after adjustments have taken place. The UK government is responsible for collecting some, but not all taxes in Scotland.

Around 8% of all taxes collected by HMRC in 2016/17 came from Scotland. That amounted to just under £44 billion. 37% of all public sector spending in Scotland was undertaken by the UK government in 2016/17. We’ve looked more at taxation and spending in Scotland here.

Any changes in the amount of this block grant from the Treasury are calculated each year using the Barnett formula.

This isn’t the only place that money for spending on Scotland comes from though. Tax powers have been increasingly devolved to the Scottish parliament, particularly since 2016, which has reduced the proportion of the Scottish budget made up by the block grant.

How does the Barnett formula work?

The Barnett formula aims to make changes to funding for services in England have the same pound-per-person effect on the money which goes to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for those services.

It’s not set out in law, and in practice the Treasury decides how to apply it. It can also be bypassed if the Treasury decides certain spending is outside the formula. If the devolved governments disagree they can argue the case.

The formula itself is basically: any change to UK government department budget, multiplied by the percentage of devolved services in that area, multiplied by the percentage population in that country.

“The energy market is owned by the French government mainly, your railways are owned by the Dutch and German government and the Royal Mail's part-owned by the German government so they are state-owned, [it’s] just not Great Britain that owns them.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 25 January 2018

Energy

The French government is a major shareholder in one of the Big Six energy providers in the UK. EDF Energy is part of the French EDF Group. The French government is the majority shareholder in the group, with 83% of shares, as of September 2017.

Of the other big six energy companies, E.ON is based in Germany. N Power is part of the Innogy group, another German company. Scottish Power is part of the Iberdrola Group (a company based in Spain).

British Gas is part of UK-based company Centrica. SSE is also a UK-based company.

Rail

Railway infrastructure—things like the tracks, signals, level crossings, bridges, and tunnels—is run by Network Rail, which describes itself as a “public company, answerable to Government”. Trains, most smaller stations, and routes are split into franchises run by different companies. Around a dozen of the franchise holders are linked to governments in other countries.

A German company, Deutsche Bahn, runs several UK rail franchises—Arriva Trains Wales, Chiltern Railways, CrossCountry, Grand Central, and Northern. The German government is Deutsche Bahn’s majority shareholder.

Rail travel in France is run by a state-operated rail company, SNCF. SNCF is also the majority shareholder in a French private transport firm called Keolis which in turn jointly runs railway company Govia with the UK Go-Ahead Group. Govia operates UK franchises: Thameslink, Southern, South Eastern, Great Northern, and Gatwick Express.

Greater Anglia, Stansted Express and Scotrail are all operated by Abellio. Abellio is run by Netherlands Rail whose only shareholder is the Dutch government.

Abellio has partnerships with other businesses to run rail franchises. Along with the Japanese companies Mitsui & Co. and East Japan Railway it runs London Northwestern and West Midlands Rail. Abellio also runs Merseyrail with UK-based Serco.

The c2c franchise is operated by Trenitalia. Trenitalia is part of the FS Italiane Group which is owned by the Italian government.

Other franchise holders are UK companies FirstGroup, Stagecoach, and Virgin Trains (which is in part run by the Virgin Group and partly by Stagecoach).

Post

Royal Mail was privatised in 2013 and the government sold its final shares in the company in 2015. As of 2016/17, 12% of the company shares were held by employees. We’ve not seen a full list of shareholders and have asked the Royal Mail for more information.

Another delivery company, UK Mail, is part of Deutsche Post DHL Group. 21% of Deutsche Post DHL shares are held by KfW Bankengruppe, whose only shareholders in turn are the German federal government and various German state governments. This may have been what the audience member was referring to.

“And because of the quite, quite meaningless limits set on what people can earn, we can't attract junior doctors from around the world because they won’t actually earn enough to meet the minimum income requirements”.

Maggie Chapman, 25 January 2018

A junior doctor’s basic salary during their first year is below the minimum required to get the relevant visa to work in the UK—unless they’re aged under 26, in which case the minimum salary is lowered. Junior doctors who’ve completed their first year will usually earn more than the minimum requirements.

However, in recent months, the amount junior doctors have needed to earn to be eligible for a visa has been unusually high due to a combination of high demand for visas and the government’s cap on skilled immigration from outside the EU. In December 2017 the threshold was effectively £55,000, and it was £50,000 in January this year—more than is typically earned by a junior doctor at any point.

Non-EEA students who graduate from a UK medical school, and then extend their visa to study as a junior doctor, are not subject to these visa requirements.

What are the earnings limits?

The Scottish Green Party pointed us to these guidelines from the BMA, which explain the salary requirement for doctors on a Tier 2 visa.

A Tier 2 (General) visa is required for people from outside the European Economic Area who have been offered a skilled job in the UK. Skilled jobs include “medical practitioners”—the category to which junior doctors belong.

A junior doctor is someone who has completed their medical degree and is now in further training, which normally takes 3-8 years. Although they cannot practice medicine independently, they make up almost half of NHS doctors, and could give you diagnosis or put you under anaesthetic.

As well as meeting the skills criteria, in order to get a Tier 2 (General) visa an applicant must be paid a minimum of £30,000 a year, or the appropriate salary for their job, whichever is higher.

The appropriate salary for a junior doctor (as set out by the Home Office) varies according to which year of training they are in. In the first year of training, the appropriate salary is £26,350—but a first-year junior doctor on a Tier 2 visa would have to earn £30,000. From the second year of training onwards, the appropriate salary for a junior doctor is higher than the £30,000 threshold.

Similarly, the NHS says that the basic starting salary for a junior doctor in their first Foundation year is £26,614, rising to £30,805 in the second year. A junior doctor starting specialist training (after a two-year Foundation Programme) has a basic starting salary of £36,461, rising to £46,208.

So a non-EEA individual applying to start the two-year Foundation Programme would not be expected to earn enough to be granted a Tier 2 visa.

However, those aged under 26 are subject to a reduced earnings threshold of £20,800 if they are sponsored for a Tier 2 (General) visa of no more than 3 years. The Foundation Programme told us that a Tier 2 visa would initially be granted to a Junior Doctor for the 2 years of their foundation training, and they would then extend their visa after applying for specialist training. This means junior doctors under 26 would be eligible for the lower income threshold.

Oversubscription automatically excludes Tier 2 applicants

Even if we assume they pass the earnings threshold, the limited number of Foundation Programme places available puts another limit on non-EEA junior doctors.

Health Education England (HEE) told us that historically the Foundation Programme has been oversubscribed, and they said this means Tier 2 visa applicants would fail the resident labour market test. This test asks the recruiting organisation to first assess whether the “settled workforce” can fill vacant posts, before it offers positions to workers from outside the EU. As the Foundation Programme was oversubscribed, those on Tier 2 visas would not have been considered.

However, HEE said that there has been undersubscription over the last two years, meaning that applicants requiring Tier 2 visas would have be considered more recently. But it’s unclear whether these applicants would be able to successfully apply, given the ambiguities about the earnings threshold.

The earnings threshold was effectively £50,000 in January

The £30,000 threshold has also effectively been inflated by quotas on the number of Tier 2 visas set by the Home Office.

Each year the Home Office puts a limit on the number of skilled workers who can come to the UK from outside the EU. These workers need to apply for a visa and have a sponsoring employer in the UK lined up. The employers themselves need to apply to the Home Office beforehand for certificates that allow them to sponsor workers who they want to employ.

The Home Office limits this kind of immigration by restricting how many certificates it gives out. In 2017/18, this limit was set at 20,700. Some immigrant workers—such as those earning £160,000 or more—aren’t capped in the same way.

Each month a limited number of certificates are allocated. If the number of applications is too high for that month, a points system determines who gets the certificates.

So if there are a high number of applications in a single month, the number of points you need is likely to be higher too. In December 2017, around 1,500 certificates for visas were granted, and applicants had to score a minimum of 55 points to make the cut—higher than the usual 21.

Points are awarded according to the type of job and salary level of an applicant. In terms of job type, most junior doctors will score 20 points unless there is considered a shortage in their specific occupation. This is the score awarded if an applicant’s proposed employer determines that there is no “settled worker” able to fill their role.

That means that in December a junior doctor would have needed to score at least 35 points on the salary scale—so they must have been in line to earn at least £55,000. This is higher than a junior doctor salary at any level.

In January 2018 the points score needed was 46. This means that most junior doctors would have to be in line to earn at least £50,000 to get a visa.

The other way to score points is if a visa applicant’s proposed job is suffering from a shortage of workers—this is worth 135 points, and so will virtually guarantee making the cut in any given month. Some trainees in emergency medicine and psychiatry are currently included on the shortage occupation list, but all other junior doctors are not (even though the Foundation Programme has been undersubscribed in the past two years).

Additional visas may be granted in in “compelling” circumstances such as there being an urgent need for an applicant to begin immediately (for instance to perform life-saving surgery). The number of visas granted for this reason was exceptionally high in December 2017, but we don’t know who they were granted to.

Thinking beyond just junior doctors, the government estimates that a third of Tier 2 visas go to the NHS. A spokesperson for Cambridge University Hospitals is reportedas saying that “Cambridge University Hospitals, which is proud to have more than 84 nationalities working at the trust, was disappointed to learn that visas for three overseas doctors due to join us in February have been declined because they do not meet a criteria that includes a salary threshold of £55,000.” We don’t know if any of these individuals were junior doctors.

Yet 17% of junior doctors are non-EEA nationals

Despite all this, 17% of NHS England junior doctors were non-EEA nationals at the end of September 2017. Based on the full-time equivalent figure it’s 18%. That’s a slightly higher level than the for all NHS England doctors, which is 16% based on both headcount and full-time equivalent.

How is this the case if they do not earn enough to enter the Foundation Programme?

It’s because non-EEA junior doctors who received their medical degree in the UK are not subject to the same immigration criteria. They can apply to extend their existing Tier 4 visa instead, which is not subject to the same earnings thresholds. Non-EEA students who have completed their studies in the UK will already be on a Tier 4 visa, and they can have their leave to remain extended if they successfully obtain a place on the junior doctor Foundation Programme.

The Foundation Programme told us that, over the last five years, an average of 520 doctors a year begin the Foundation Programme on a Tier 4 visa. So the majority of non-EEA junior doctors are likely to be on Tier 4 visas, having completed their medical degrees in the UK. The BMA suggests that it is "very rare" for non-EEA individuals to be sponsored for Tier 2 Visa for the junior doctor Foundation Programme.