BBC Question Time: factchecked

This week Question Time was in Dartford. On the panel were minister of state for energy and clean growth Claire Perry MP, Labour's shadow secretary of state for international trade Barry Gardiner MP, fund manager and campaigner who took the government to the Supreme Court over Brexit Gina Miller, former editor of the Daily Telegraph and The Spectator Charles Moore, and the broadcaster and journalist Piers Morgan. We factchecked claims on the government's plans for customs arrangements after Brexit, how many constituencies voted to leave the EU, how much we contribute to the EU budget, and how much of our trade is done via WTO rules.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

"It was the case, the Prime Minister said that Brexit meant Brexit, now Brexit means that we are becoming the tax collector for the European Union, collecting the tariffs for the European Union on all the goods that come into this country that are directed towards Europe."

Barry Gardiner MP, 12 July 2018

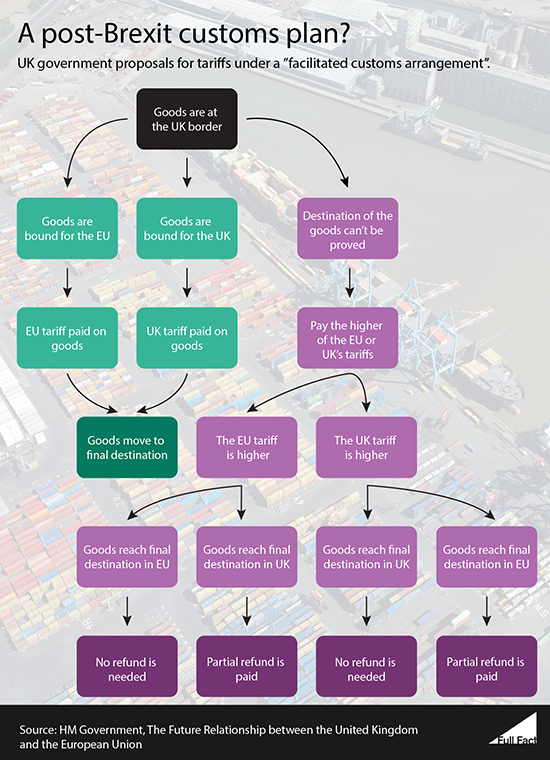

UK government proposals for a customs agreement with the EU unveiled this week would involve collecting taxes on goods at the UK border, set at either the UK or EU rate.

Proposals published by the government outline, among other things, a “facilitated customs arrangement” which will be phased in to replace the current relationship the UK has with the EU as part of the customs union.

At the moment, being part of the EU customs union means that there are no barriers to trade—for example in the form of import or export taxes—on goods moving between EU countries. It also means that all EU countries charge the same tariffs on goods entering the EU from the rest of the world.

The government’s position is that, once we leave the EU, the UK will also leave the customs union.

The government says the “facilitated customs arrangement” would secure “the most frictionless trade possible in goods between the UK and the EU, while allowing the UK to forge new trade relationships with partners around the world.”

It says the plan would ensure that the correct customs rules are applied and taxes have been paid on goods destined for the EU via the UK. When goods come into the UK they will need to show which country they are bound for. If this can be shown clearly by a “trusted trader” then they will need to pay the UK government the appropriate level of tax—either the UK’s level or the EU’s depending on the destination.

If the destination of the goods can’t be shown clearly then the trader will need to pay whichever tax is higher—the UK’s or the EU’s. Once it reaches its final destination the trader can then apply for a refund from the government if it turns out they paid the wrong rate.

The government has also proposed that “Where there is a material risk of circumvention of higher UK tariffs, the UK would make it illegal to pay the wrong tariff, and use risk and intelligence based checks across the country, rather than at the border, to check that the right tariffs are being paid.”

The government's proposals say that “The UK and the EU should agree a mechanism for the remittance of relevant tariff revenue [...] the UK proposes a tariff revenue formula, taking account of goods destined for the UK entering via the EU and goods destined for the EU entering via the UK. However, the UK is not proposing that the EU applies the UK’s tariffs and trade policy at its border for goods intended for the UK.”

The government has also proposed that there will be no taxes on trade directly between the UK and EU and traders wouldn’t normally need to prove where the goods came from—this is based on the fact that the goods should have already been checked and taxed at the appropriate level when they entered the proposed UK-EU free trade area.

The government says these proposals “would enable the UK to set its own tariffs and vary them as it chooses”.

The EU is considering the government’s proposals and will meet next week to discuss them further.

"7 out of 10 Conservative MPs... represent constituencies that voted to leave, as did mine. 6 out of 10 Barry’s party [Labour] represent Leave constituencies."

Claire Perry MP, 12 July 2018

The results of the EU referendum weren’t counted by parliamentary constituency, so we don’t know for sure how constituencies voted. A small number of councils did release official breakdowns by parliamentary seat, and data on some other areas was obtained by the BBC via Freedom of Information requests.

The best figures we have for other constituencies comes from Professor Chris Hanretty, a political scientist at Royal Holloway University, who combined official results and the BBC data with statistical methods in order to estimate the proportion of Leave and Remain voters in every seat in England, Scotland and Wales.

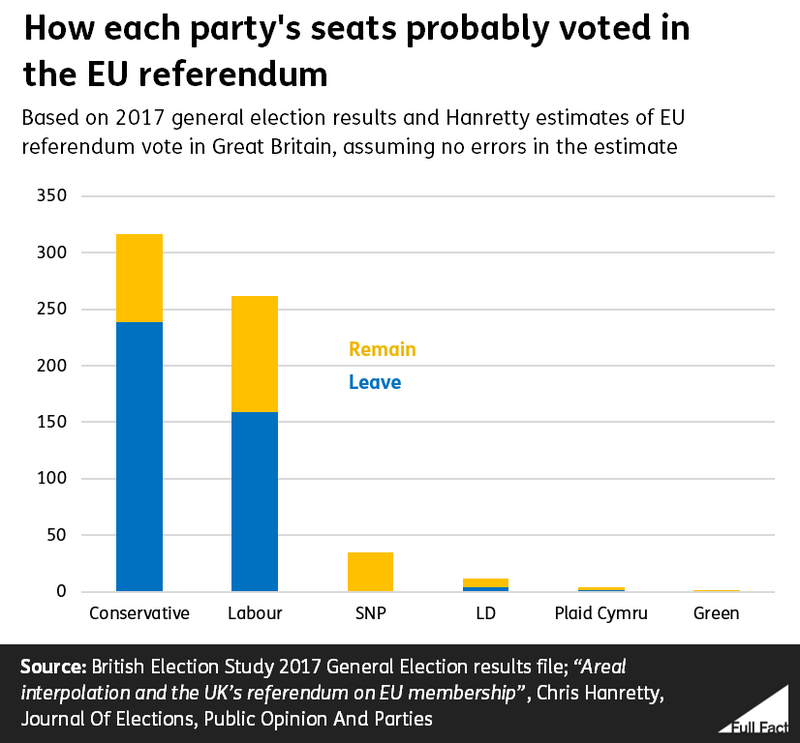

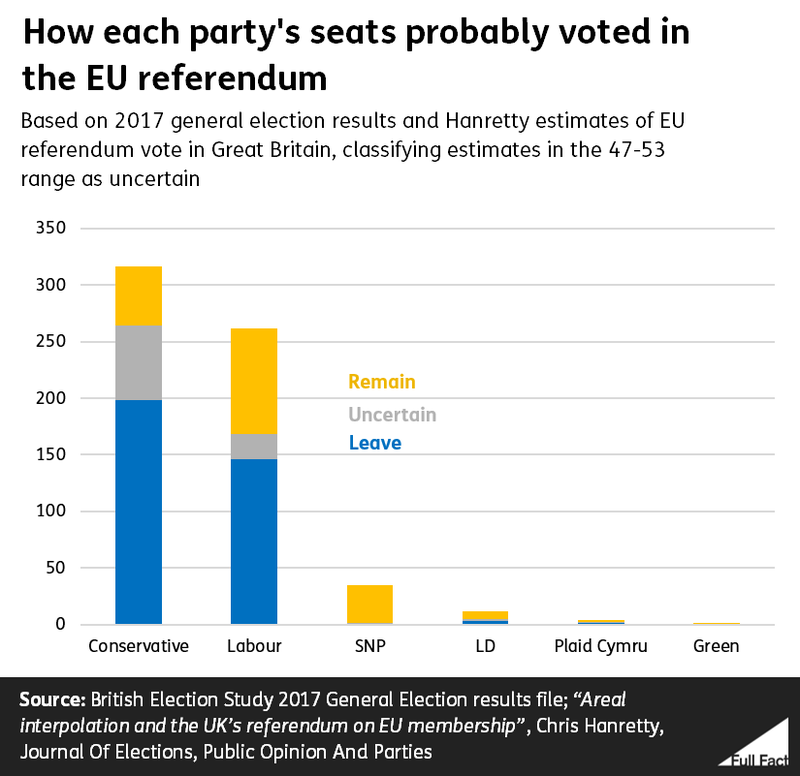

These estimates show that while the national result of the referendum was relatively close, with 52% voting Leave and 48% voting Remain, a much larger majority of parliamentary seats voted to Leave – with 64% of seats in Great Britain voting Leave. (This is likely due to the uneven distribution of Remain voters, who tended to cluster in large cities, while Leave voters were more evenly spread.)

According to these estimates, around 75% of constituencies that were won by the Conservatives in the 2017 general election voted to Leave, while around 61% of Labour constituencies voted to Leave. All seats won by the Scottish National Party and the Green Party, and a majority of the seats won by the Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru, voted to Remain.

These estimates are most likely the ones being referred to when politicians discuss how constituencies voted. But other than the seats where the actual result is known for sure (only 20% of constituencies) they are just estimates.

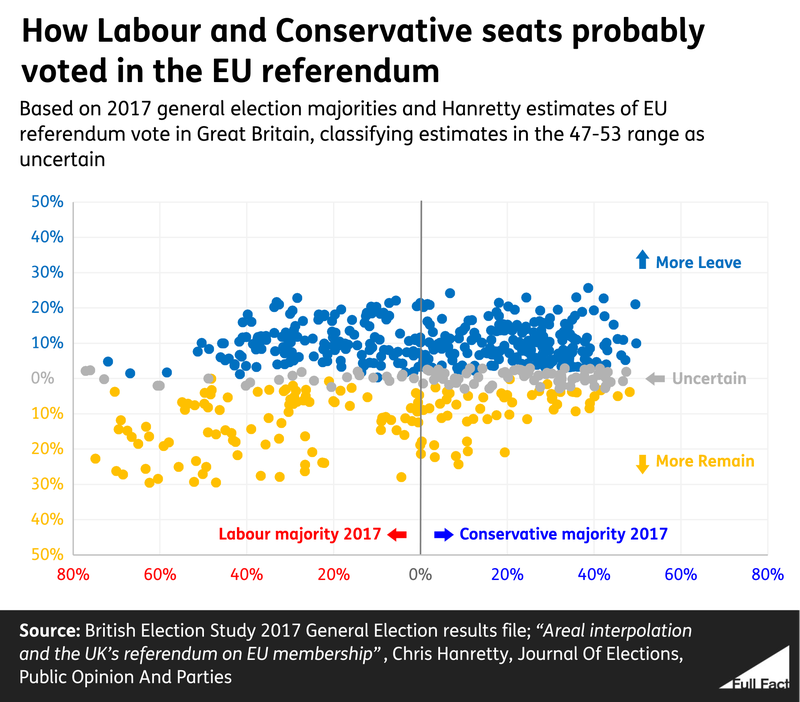

As Professor Hanretty wrote when he released his work, “I’d like you to say ‘probably’ before you talk about how a constituency voted, unless I’ve flagged up a result as being known exactly.” The margin of error for the estimates is not known, due to the nature of the statistical methods used.

This means that for constituencies in which the exact results are unknown, and which the estimates suggest the result of the referendum vote was close, we can’t be certain about saying whether the constituency voted Leave or Remain.

Looking just at seats held by the Conservatives and Labour, if we highlight seats where the estimated referendum vote was within the 47% to 53% range and the actual result isn’t known, we can see that there are a large number of seats where the referendum vote is still uncertain.

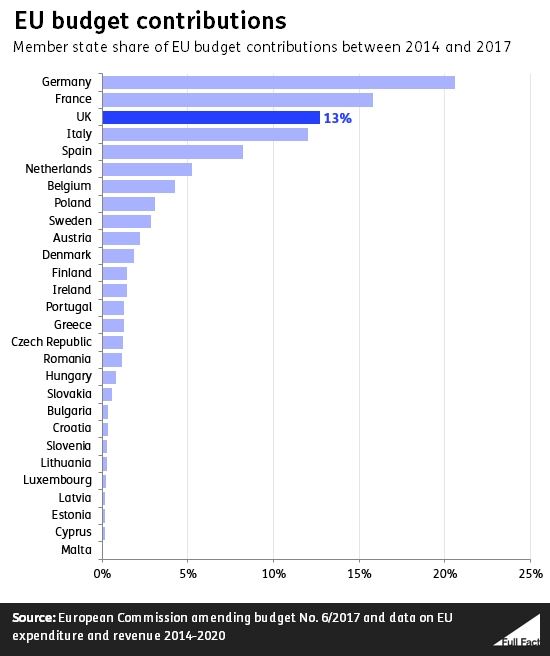

“With all the money that we put into it (the EU), we are one of the three countries that put the most money into it”.

BBC Question Time audience member, 12 July 2018

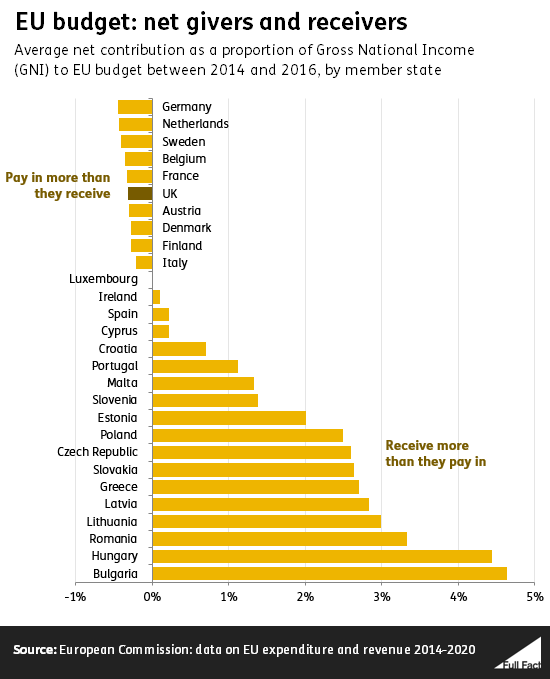

This is correct, referring to the EU budget. The UK has been the third or fourth largest contributing country to the EU budget in recent years, and of the 28 EU members is one of 10 to contribute more than it gets back in receipts.

The UK also gives and receives much more money via trade with other EU countries, so transactions with the EU budget aren’t the full story when it comes to the UK’s economic relationship with the rest of the EU.

Each country pays a ‘membership fee’ and gets benefits

Each EU member state has to contribute money to the EU budget each year, and each member state gets funding back which is spent in their country on various kinds of projects.

Payments into the EU come in three types. The biggest by far is a payment based on the size of each country’s economy, called a GNI (Gross National Income)-based contribution. Countries also pay money based on how much they make in VAT, and on customs duties on their imports from countries outside of the customs union.

The UK, being one of the EU’s largest economies, pays more than most members. Only Germany and France consistently contribute more funding, while Italy pays about the same amount.

The UK’s rebate is a discount on its contributions so it reduces what it would otherwise pay, and increases what other member states pay. Without the rebate the UK would be the second largest contributor behind Germany.

Factoring in money that comes back as well, the UK is one of 10 countries that pay more in than they get back. Relative to the size of their economies, Germany and the Netherlands are the biggest contributors and Bulgaria and Hungary are the biggest receivers.

When the UK leaves the EU, it won’t continue to pay annual budget contributions, although it will settle a divorce bill agreed with the EU to settle outstanding liabilities, and the government has already indicated that, until at least 2022, it will continue to spend some money on the areas where the EU currently gives us funding.

As we factchecked recently, that means there is no guaranteed extra money—or ‘Brexit dividend’—to pay for public services as a result of ending the UK’s payments to the EU budget.

“There are WTO rules which govern world trade, and most of our dealings with most countries in the world are based on WTO rules.”

Charles Moore, 12 July 2018

Most of the UK’s trade is with the EU or countries the EU has trade agreements with—about 57% of our exports and 66% of our imports in 2016. That means it doesn’t happen under standard World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

But EU trade agreements don’t affect tariffs on all goods and services. Some goods and services have the same tariff level for countries the EU has trade agreements with and those it doesn’t.

If the UK were to leave the EU with “no deal”, we would go back to trading under WTO terms with these countries.

The WTO prevents discriminatory tariffs, except between countries with trade deals

In a nutshell, the WTO is an international organisation aiming to reduce all barriers to trade. Most countries around the world are members, including the UK.

The WTO requires member countries to apply tariffs (taxes) on goods and services to other WTO countries equally. It also means you can’t set different rules for foreign and domestic products in your country. The big exception is if countries have negotiated their own customs union or free trade area.

You can read more about how the WTO works here.

Most of our trade is with countries the EU has a trade agreement with

The main exception to WTO trade rules that apply to the UK is that we’re a member of the EU customs union and so have free trade with other EU members. In 2016 44% of our exports in goods and services went to other EU countries and 54% of our goods and services imports came from EU countries.

The EU also has trade agreements with other countries, like Israel and South Korea. Countries where there is an EU trade agreement in place accounted for a further 12% of our imports and 13% of our exports.

The EU also has “preferential trade agreements” with various other countries. This is where one country grants preferential tariffs on imports from developing countries. As these arrangements are unilateral (they’re one way and so don’t require a two-way trade deal), we’ve not included these countries in our calculations.

So in total 57% of our exports and 66% of our imports happen with countries we have some trade agreement with as part of the EU. The EU has also negotiated or is in the process of negotiating trade deals with other countries, including Japan and Australia.

However WTO rules don’t always mean tariffs

Free trade agreements that change tariffs between countries from the WTO default don’t necessarily affect all goods and services. While 57% of the UK’s exports go to the EU or other countries with which we have some kind of trade agreement, that doesn’t mean that a “no deal” situation would mean new tariffs on 57% of our exports.

For example, take bottled beer. At the moment the EU, and therefore the UK, has no trade deal with the USA and it pays no tariffs on the bottled beer it exports there.

If the UK was to revert to trading with the EU under WTO rules following Brexit, there would similarly be no tariffs on the export of UK bottled beer to the EU.