BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Blackpool this week. The panelists were: Conservative MP and former-Chancellor Ken Clarke MP, shadow secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Owen Smith MP, former-leader of UKIP, Nigel Farage MEP, businesswoman and former Apprentice winner, Michelle Dewberry, and Blue Peter presenter, Radzi Chanyanganya. We looked at claims on: wind power, Nigel Farage's views on another EU referendum, and EU trade agreements.

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“Nigel Farage, you once flirted with the idea of a second referendum?”

David Dimbleby, 1 March 2018

“No, I didn't, I said I feared. I feared because there is a great Brexit betrayal going on, that parliament may force a second referendum upon us. I pray they don’t, but I do fear and I think some of the people in this panel would like a second referendum.”

Nigel Farage MEP, 1 March 2018

In three media appearances in January, former UKIP leader and Brexit campaigner, Nigel Farage, suggested that a second referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union may happen and on several occasions said that he feared this would be the case.

In one interview he also said that he was perhaps reaching the conclusion that it should happen as he felt the proportion of people voting to leave the EU would be larger than in the 2016 referendum.

We’ve based this article on clips of interviews that have been shared by the various TV and radio shows Mr Farage appeared on.

In an appearance on The Wright Stuff Mr Farage said “What is for certain is that the Cleggs, the Blairs, the Adonises, will never ever, ever give up. They will go on whinging and whining and moaning all the way through this process. So maybe, just maybe I’m reaching the point of thinking that we should have a second referendum on EU membership. [...] I think if we had a second referendum on EU membership we’d kill it off for a generation. The percentage that would vote to leave next time would be very much bigger than it was last time round.”

After the interview, the then leader of UKIP, Henry Bolton, said that UKIP are opposed to a second referendum.

On the same day, Mr Farage appeared on his LBC radio show, where he said “I fear that Parliament will reject any deal. And I fear that Parliament, both the Commons and the Lords, may well do anything they can to put us through a second referendum. [...] This deal with Europe has to be finished by October. It could be before the end of this year that parliament is voting on the final deal… So much as I don’t want a second referendum, I have now begun to open my mind to the possibility that this will be forced upon us.”

At the end of the month Mr Farage was interviewed on Good Morning Britain and discussed a possible vote on the final EU deal with Liberal Democrat Leader Vince Cable, Susanna Reid and Piers Morgan. He said again that he feared a second referendum as “a majority in parliament reject Brexit”, but that he personally didn’t want one.

“In the modern world, 60% of our trade, if you count all the EU deals that we're members of, 60% of our trade is in trade agreements.”

Ken Clarke MP, 1 March 2018

In 2016, around 54% of the UK’s exports were to countries which had trade deals in place or provisionally in place with the EU (including EU member states). 60% is a little high, according to our calculations.

These deals are designed to make trade easier, with fewer tariffs in place. As the UK is currently part of the EU, it traded with those countries through the EU agreements in 2016.

When the UK leaves the EU, it will leave those trade agreements, but will then be able to negotiate its own separate agreements with states. We can’t say for certain how this will affect the UK’s exports.

Research by the think tank Open Europe in 2015 estimated that 59% of UK exports were via EU trade agreements, but we haven’t verified that calculation.

What is a trade agreement?

Trade agreements set special rules between trading partners, with the aim of making trade easier.

One example is the EU Customs Union, which removes customs duties and checks between trading partners. It also ensures that all partners set the same tariffs on imports from outside the Union (ensuring members don’t set lower tariffs for non-Union members).

The EU has two other kinds of free trade agreement in place: agreements which remove or reduce tariffs between trading partners (without harmonising tariffs on other foreign imports), and agreements which “provide a general framework for bilateral economic relations” but do not change customs tariffs.

As a current EU member state, the UK is a part of all of these agreements, and cannot negotiate separate agreements.

The UK will no longer be a part of these agreements when it leaves the EU, so will be able to negotiate its own separate agreements.

How many countries does EU have an agreement with?

It’s roughly 60-70 outside of the EU. It’s not easy to tell exactly how many countries are involved, as some agreements are not fully negotiated, or not all partners have signed up yet.

As an EU member, the UK can trade tariff-free with all 27 other EU member states through the single market.

On top of this, the EU lists 31 states or territories with which it has some kind of trade agreement fully in place (in a few cases this gives them access to the single market).

The EU lists over 30 more countries where agreements have been provisionally applied—meaning that the agreement has not yet been ratified by every signatory state (which includes all EU member states).

It’s unclear what that means in every specific case, but moving from a provisional to full application can take years to complete, and a lot of the agreement can still start to happen in practice, before the formal process is completed.

For instance, a free trade deal with Canada was provisionally applied in September 2017, and all aspects are in force except for a few relating to investment.

How much of UK trade is through EU trade agreements?

In 2016, around 53% of UK trade went to states with which the EU had a trade agreement fully in place. That rises to 54% if we include all states where an agreement was provisionally in place by January 2016.

43% of UK exports went to the European Union in 2016, rising to 49% when including other members of the EU Customs Union and European Free Trade Association.

The number of EU trade partners has risen since then. In 2016, Canada and several African countries were not part of trade agreements with the EU—so are not included in the 54% figure, but would be counted as EU trading partners today.

Japan concluded an agreement with the EU in December 2017, but it has not yet been signed—so is yet to be “provisionally applied”. Armenia, Singapore, and Vietnam are also recorded as having agreements “pending”.

Together, Canada and Japan accounted for 4% of UK exports in 2016, with no EU trade agreement in place to facilitate trade. We don’t know how UK trade with Canada and Japan will be affected after Brexit, now that they have provisional/pending trade agreements with the EU.

If you count the countries as a block, the EU is the UK’s single biggest export market. The second biggest market is the USA (18% of UK exports)—which is not part of a trade agreement with the EU. Other notable economies which aren’t part of EU trade agreements are China (3% of UK exports) and India (1% of UK exports).

The EU says it has been or is negotiating deals with the USA, China, and India (among others). It’s unclear how advanced the negotiations are though, and those with the USA have been put on hold.

After leaving the EU, the UK may negotiate its own trade deals with these countries, although we don’t yet know if this will happen.

“And a quarter of the energy we are using in Britain today has come from wind”.

Owen Smith MP, 1 March 2018

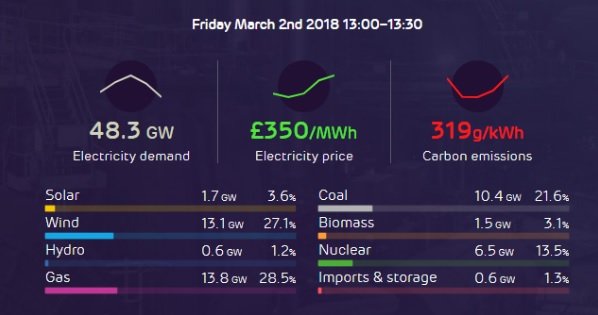

At the time of writing, wind power is currently generating about a quarter of the UK’s electricity, about the same as gas. That’s according to live data taken from the National Grid and electricity administrators Elexon. That includes both on- and offshore wind generation.

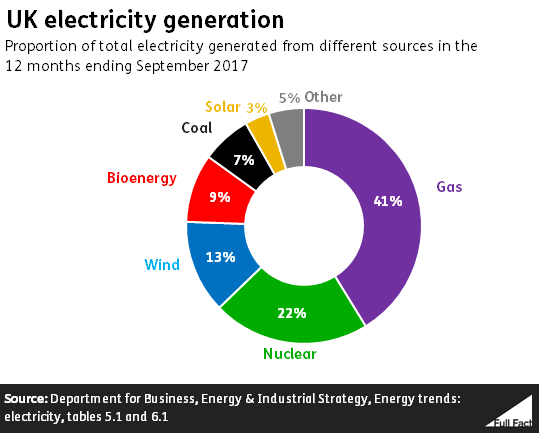

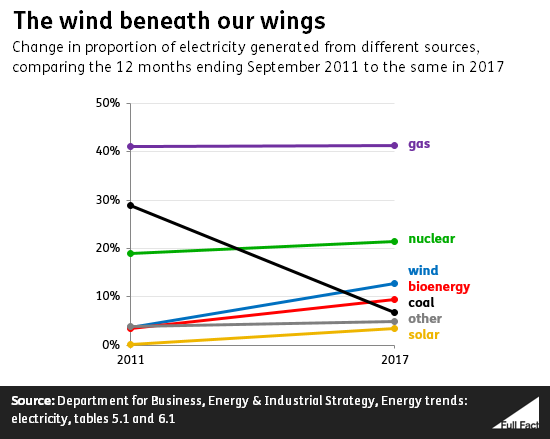

Wind generated something like 15% of the UK’s electricity generation in 2017, and 13% using the latest official figures for the 12 months up to September last year. Gas remains the single biggest source of electricity by far.

That’s because of a mix of increased wind capacity, falling coal production and market pressures on coal.

The large drop in coal is because of closures to coal plants in the UK, the conversion of existing coal generators to biomass, and market factors. As the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy says: “Whilst fuel costs for coal-fired generation are lower than for gas, emissions from coal are higher so generators must pay a greater carbon price per GWh produced.”

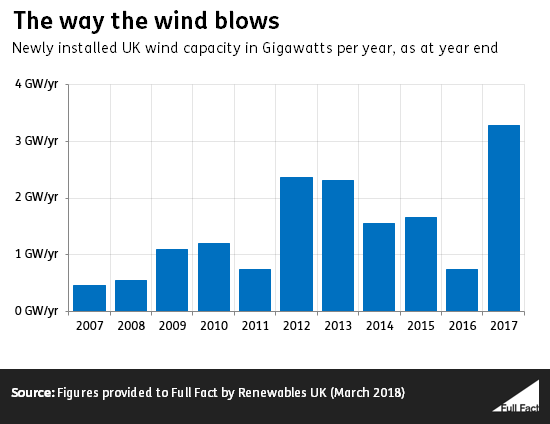

This has been combined with a large increase in the UK’s wind generation capacity. The trade association RenewableUK provided us with figures showing the total installed capacity of wind generators has doubled since 2012.

Some of the electricity supplied in the UK comes from imports from the continent. The UK currently imports far more electricity than it exports.