BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Dover this week. The panelists were: Transport Secretary Chris Grayling, Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer, Irish MEP and Vice President of the European Parliament Mairead McGuinness, Russia Today presenter Afshin Rattansi and Hollywood actor and SNP supporter Brian Cox. We looked at claims on political party donations, the size of the UK economy and the Brexit divorce bill. We’ll be publishing a further piece factchecking Keir Starmer’s claims about lorries at Dover next week.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“There are strict laws on political donations in this country. They have to be given by British citizens, or British businesses … The simple reality, you can't accept money from people who are not UK citizens, or UK businesses.”

Chris Grayling MP, 15 March 2018

Political parties in the UK are restricted in who they can accept donations from. Individual donors have to be British citizens, or Irish, EU and Commonwealth citizens living in the UK.

A donation in the UK is: “money, goods or services given to a party without charge or on non-commercial terms, with a value of over £500.”

According to the Electoral Commission, UK political parties can only accept donations from “permissible donors”. Individuals must be on the electoral register to donate, which broadly means they have to be a British citizen, or an Irish, EU or qualifying Commonwealth citizen living in the UK.

You can’t register to vote if you’re solely a Russian citizen, for example, and so you wouldn’t be able to make a donation to a UK political party. Russians who have taken British citizenship can donate.

The rules also say that only UK businesses can donate to parties in Great Britain and only UK and Irish businesses can donate in Northern Ireland, and the Electoral Commission lists the details of who’s included in that for Great Britain and Northern Ireland separately.

The laws were originally introduced in 2000, partly in response to concerns that foreign sources could donate to political parties in the UK.

Parties are able to get funding from other sources too, including loans (which follow the same rules as donations), membership fees and some public funds.

“We are the second largest economy in the EU”

BBC Question Time audience member, 15 March 2018

GDP—‘Gross Domestic Product’—is the main measure of the size of the economy.

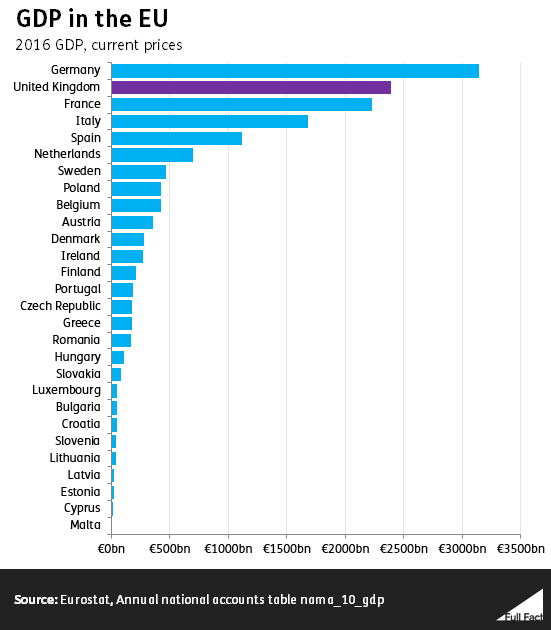

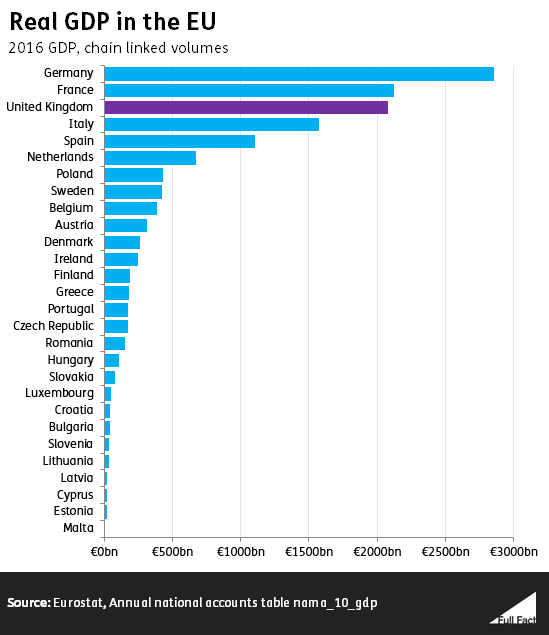

The UK is one of the largest economies in the EU. Its exact position depends on which measure you use. GDP can be measured in two main ways—including or excluding the effect of price changes over time. Nominal GDP, or GDP at current prices, includes these effects. And real GDP, or chain linked volume measures, remove them, keeping prices constant.

Real GDP is useful for comparing the amount produced now with the amount in the past. If the same number of goods are produced in two years, we wouldn’t think production has increased. But if the price of those goods has increased, nominal GDP would rise.

In 2016, measured in current prices and in euros, the largest economy in the EU was Germany, followed by the UK and France.

Germany also had the highest level of real GDP, followed by France and then the UK in third place.

We can also compare how quickly GDP is growing in EU countries. UK real GDP grew by 1.9% in 2016, the seventh slowest in the EU. Nominal GDP fell nearly 8% in 2016 (the slowest growth in the EU), due to changes in the exchange rate. The pound fell 14% against the euro in 2016.

As we’ve written before, GDP figures are often revised as time goes by, so this picture may change with subsequent data releases.

There are also some aspects of the economy that GDP doesn't necessarily measure. For example:

- It doesn’t capture some aspects of people’s wellbeing or everyone’s experience of the economic situation.

- It doesn’t reflect the environmental impacts of economic growth, such as pollution

- It excludes unpaid work, such as housework and childcare.

- It may not be accurately capturing improvements in digital technology, or the value of digital services provided for free.

More information about GDP can be found in the Bank of England’s Knowledge Bank.

“We are going to be paying until 2064, apparently”

David Dimbleby, 15 March 2018

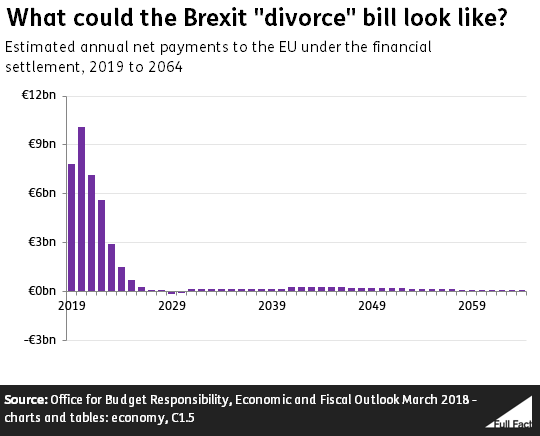

This is correct, according to estimates released this week about the Brexit “divorce bill” from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The joint statement from the UK and EU published in December—at the end of phase one of the Brexit negotiations—set out the details of the Brexit bill the UK will have to pay. Until 2020 the UK will continue contributing the the EU budget “as if it had remained in the Union”. After that it will continue paying towards any commitments it has or outstanding liabilities (for example pensions).

Based on this agreement the OBR estimates that the final cost of the Brexit bill will be around £37 billion in total.

Around 45% or £16 billion will be paid in the first two years—this will be the contribution to the EU’s budget. About half will be due between 2021 and 2028—£18 billion—in outstanding payments. The remaining 7%—£2.5 billion—will be due between 2019 and 2064. This will cover any outstanding liabilities.

We’ve written more about the Brexit “divorce bill” and previous estimates for how much this might cost here.