BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in St Albans this week. On the panel were minister for the Cabinet Office David Lidington MP, Labour shadow business minister Chi Onwurah MP, comedian and broadcaster Matt Forde, political editor of the Sunday Express Camilla Tominey and broadcaster and founder of MoneySavingExpert.com Martin Lewis. We factchecked claims on UK population change, House of Lords allowances, non-decent homes, post-Brexit economic forecasts, and whether student loans count as debt.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We have an expanding population. We have more households because of social change and people living longer for any given level of population than we had a generation ago.”

David Lidington MP, 3 May 2018

The population of the UK is expanding. It was estimated to be 66 million in 2016, compared to 61 million ten years before.

The main driver of increased population has been immigration, according to the Office for National Statistics. Life expectancy in the UK has also been steadily increasing over the last few decades.

The average household size has not changed much in the last two decades, since current figures began. There are on average 2.4 people per household, and that’s been true every year since 1996.

Out of 27 million estimated households in the UK, the most common type belongs to the 16 million couples living together with or without children. 8 million households are one person living alone, and there are 3 million lone parent households.

There are also around 306,000 households with multiple families living in them, this has been the fastest growing group over the last decade. The Office for National Statistics says this “may be because of older couples moving in with their adult child and their family, young adults who are partnered or lone parents, remaining or returning to their parent’s household and unrelated families sharing a household.”

“They [the Lords] get 300 quid a day.”

Camilla Tominey, 3 May 2018

Most members of the House of Lords don’t receive a salary, unless they are a minister or hold some other office.

Those who aren’t salaried may claim a daily allowance of £300 for each “qualifying day of attendance” in Westminster. They can choose to claim a reduced rate of £150 instead, or not claim at all. If they are working away from Westminster on parliamentary business they can only claim £150 a day, as well as some travel expenses.

Those paid a salary cannot claim this attendance allowance.

Attendance can include sitting in the House of Lords when formal business takes place, and attending other specific committees and meetings. There are also certain events they cannot claim attendance allowance for, like the State Opening of parliament, or speeches by visiting dignitaries.

On top of the daily allowance, members can claim expenses for some travel. Lords who are paid a salary can also claim for some expenses, for example secretarial expenses.

Expenses and allowances for unsalaried members of the Lords are not subject to tax or national insurance contributions as membership is not classified as employment.

Full disclosure: several of Full Fact’s trustees are members of the House of Lords.

“When we were in office, what we did was we rebuilt, we renewed 1.4 million homes which were in dire circumstances because of the previous government. So you can argue that we should have built more homes, and I think we should have as well, but we actually made 1.4 million homes in this country habitable.”

Chi Onwurah MP, 3 May 2018

In 2000, the Labour government introduced a “Decent Homes Programme”, with the target of bringing all social housing in England up to a decent standard by 2010.

A decent home is defined as one which meets the minimum legal standard for housing, is in a reasonable state of repair, has “reasonably” modern facilities and services and has effective and efficient heating and insulation.

By the end of 2009, the government estimated that 1.4 million “non-decent” social sector homes in England had received work to make them habitable under the programme. That’s not the same as the fall in the number of non-decent homes though, as some homes may have become non-decent in the same period.

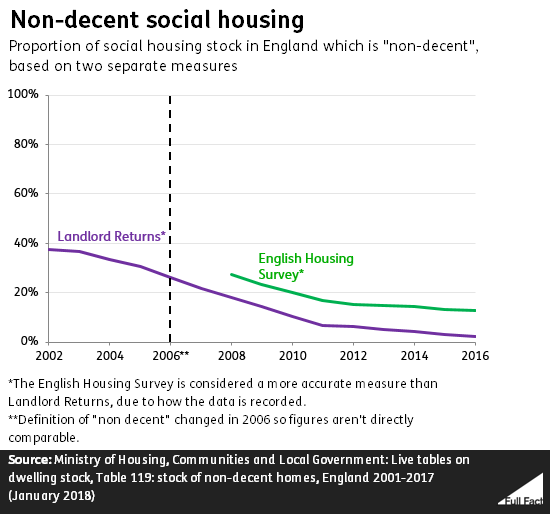

There are problems with measuring the fall in non-decent homes

The definition of a decent home changed in 2006, so we can’t fairly compare data from before and after that point. In 2002 there were 1.6 million non-decent homes in the social housing sector (or 38% of the overall stock) and in 2010 there were 400,000 (10%).

These figures are also known to undercount the number of homes though. There are more accurate figures (from the English Housing Survey) but they only go as far back as 2008—so we can’t use them to look at Labour’s record.

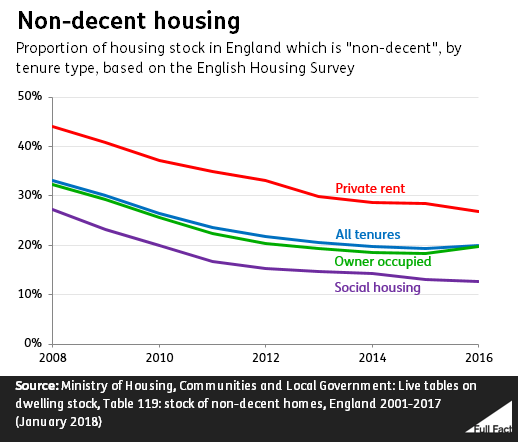

Using the more accurate figures, the level of non-decent social housing is significantly higher. By this measure there were around 760,000 non-decent social sector homes in 2010 (or about 20% of the overall stock). That’s fallen to 13% in 2016, or around half a million.

The English Housing Survey also provides data on the overall housing stock. It reports that 20% of the total housing stock (4.7 million homes) were non-decent in 2016. 27% of private rented homes were non-decent, as were 20% of owner-occupied homes.

“Condemning the economic impact [of Brexit], that the government themselves have said. A cut to GDP of between three, five, and eight percent. Whichever way you sell it, soft or hard, that is a recession.”

Matt Forde, 3 May 2018

Figures published by the government on the economic impact of different Brexit scenarios suggested that over the next 15 years economic growth might be reduced by around 2% if the UK remains in an “EEA-Type Scenario”—for example a similar sort of relationship to the EU as the one Norway has.

They are suggesting that instead of the economy growing by about 25% over 15 years, it might instead grow by something like 23%.

It suggested growth could be reduced by around 5% if the UK enters into a free trade agreement with the EU, and by around 8% if it leaves the EU without a deal and trades on World Trade Organisation terms.

In its analysis, the government said it planned to pursue “a more ambitious deal” than any of these and that the “global environment, [the] EU’s policy outlook and sectoral issues” would all affect the outcome. Overall, the government emphasised that the analysis was a work in progress and “is not representative of the expected outcome of the negotiations.”

These figures don’t mean that the government thinks there will be a recession. A recession would mean the economy is shrinking, whereas these figures are about it growing less quickly than it otherwise might have.

There are a wide range of estimates on what might happen to the UK economy in the long-term after Brexit is complete. Most predict that growth will be slower.

We’ve written more about interpreting economic models and predictions here.

“Let's just be very plain on the impact of student finances on mortgages. When you get your student finance, it works not like a loan but like a graduate contribution system... It does not go on your credit file. It is effectively like mildly increasing the amount of tax that you pay, just like increasing pension contributions also decreases your disposable income. It is not a big issue for getting a mortgage.”

Martin Lewis, 3 May 2018

The personal finance journalist Martin Lewis appearing on BBC Question Time criticised politicians for framing student loans as a debt when they don’t actually work like debts. He has a point.

The student finance system is devolved and is one area where different parts of the UK differ dramatically. For example, this argument happened in St Alban’s in England, where students are responsible for their own tuition fees and that’s what we’re looking at here. People who live in Scotland and study in Scotland aren’t usually required to pay tuition fees.

As Mr Lewis said, student loan repayments don’t work in the same way as what we usually call a debt. The government’s own website makes clear that “the size of your monthly repayments will depend on how much you earn, not what you owe.”

That’s why the MoneySavingExpert website is right to say that the headline figure for what students might ‘owe’ at the end of university is “mostly meaningless”. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that “more than three-quarters of students can expect to have some debt written off” because the repayments due with the amount they earn won’t fully repay the ‘debt’.

It’s also true that student loans do not go on your credit file. The Student Loans Company confirmed to us that: “A student loan will not affect an individual’s credit rating as long as they meet their contractual obligations.”

The obligation to pay a bit of your income (once it reaches a certain level) in order to repay student costs does reduce your disposable income. So a lender might ask if you have student loan repayments because they reduce the amount of income you have free to repay other debts.

Which? have calculated having to make student loan repayments might reduce the amount a lender might offer you for a mortgage by about £3,000-4,000 if you earn £30,000—when somebody might be able to borrow about £90,000-£130,000 overall.

It wouldn’t be right to describe the student finance system as exactly like a graduate tax either. There are some points of the student finance system which are more like loans than taxes or a ‘graduate contribution’. Nobody forces you to take a student loan if you’re rich enough not to need one, and if you’re earning enough to make enough repayments you eventually won’t have to pay any more.