Employment: How is it defined and why does that matter?

In this series of articles we try answer common questions about whether we can trust employment statistics, and go beyond the headline figures to assess the health of the labour market more comprehensively.

But to start with, it’s important to understand what “record employment” and low unemployment really mean. Various criticisms have been levelled at the statistics and concepts. So are any of them right?

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Employment is at a record high, unemployment is at its lowest since the 70s

You could measure the employment rate in a number of ways. But the official definition in the UK is the percentage of people aged 16-64 (meaning most working-age people) who do paid work for at least an hour per week.

On this measure, employment is at its highest since records began in the early 1970s, at 76%. That doesn’t mean all of the remaining 24% are unemployed though. These people may have taken early retirement, be in education or training, or simply don’t want a job.

As such, the unemployment rate is slightly different: it looks at what percentage of people who want a job and are available to work, aged 16 and over, are not in employment. The current unemployment rate is 4%—the lowest level since the 1970s.

There are several main criticisms directed towards these figures, which we’ll look at in turn.

Is the definition fiddled?

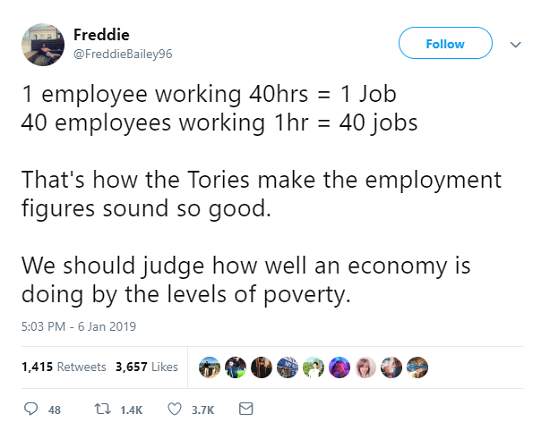

The first criticism is that the definition of employment itself is fiddled by the government in order to make the jobs market look healthier than it is.

It’s correct that you only have to work an hour a week to count as employed, but it’s not correct that the government has manipulated the definition. The current definitions of employment and unemployment were set by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1982, and not by any particular government. Most other countries also use this definition.

The ILO is an agency of the United Nations with a mission of “promoting social justice and internationally recognized human and labour rights”, comprising representatives from trades unions, employers and governments.

The ONS told us that they started collecting quarterly figures using the ILO definition from 1992 and that data from 1971-1992 using this estimate was back-calculated. Over time the ILO definitions gained prominence as the headline measure for employment.

There are several reasons why using the definition of one hour a week makes sense. One is simply that you need to draw a line somewhere, and this is the least arbitrary place to draw the line. If you set the threshold higher—say, 6 hours a week—you’d still have to explain why someone working for 5 hours doesn’t count as employed, but someone working for 6 hours does. The difference between someone working for no hours and someone working for 1 hour is a lot clearer.

Another reason is that those working very low hours may be among those more vulnerable to exploitative labour practises, and therefore it’s particularly important to include them in the definition.

How useful you think this is as a measure will depend on your own point of view. But using a single definition means that the data going back to 1971 is consistent and allows for meaningful comparisons, both over time and across borders.

Employment statistics are comparable

This is another common criticism of employment figures: that employment statistics are not comparable over time because the definitions of employment and unemployment have changed.

This isn’t entirely baseless, although it’s no longer accurate. It’s correct to say that the definition of employment in the UK has changed over time, and that in the past it changed quite frequently. But as we’ve said, the employment rate statistics used nowadays use a consistent method to calculate the rates going back to the 1970s.

A few decades ago, the unemployment rate was based on the number of people claiming unemployment benefit. So when governments changed policy to make those benefits available to more or fewer people, the unemployment rate also changed.

This had a big effect on employment statistics throughout the late 70s and much of the 1980s. A 1991 report from the Social Security Advisory Committee found the unemployment definition had been changed 20 times between 1979 and 1988, and that almost every change reduced the number of people defined as unemployed.

So comparing the unemployment and employment rates as measured in those years would have been an unfair comparison, because the definition was always changing.

But nowadays the unemployment rate (and the employment rate) isn’t affected by how many people claim benefits. Employment and unemployment is based on the number of people who do or are seeking paid work as measured by a large scale survey. Statistics using these definitions have been back-calculated going back to the early 1970s.

In summary then, the definition of employment used by official statistics is an international standard with a consistent definition, and comparisons over time to the 1970s are fair. The government isn’t fiddling the definition.

Of course, just because the definition is consistent doesn’t mean that it will necessarily give you useful data. It still might not tell you much about whether these jobs are providing the hours, stability and wages people want, and whether that has been improving or not.

In our next piece we look at one of these issues—whether using the “one hour a week” definition means that high employment rates are being artificially boosted by people working low numbers of hours. We’ll ask whether the employment rate has only increased because work is being spread more thinly.

More from this series:

- Why don't people trust employment statistics?

- Is employment up because the government is fiddling the statistics?