What was claimed

Britain gives away £13 billion a year in foreign aid.

Our verdict

The UK spent £13.4 billion on foreign aid in 2016. Provisional figures for 2017 put the amount at just over £13.9 billion.

What was claimed

Britain gives away £13 billion a year in foreign aid.

Our verdict

The UK spent £13.4 billion on foreign aid in 2016. Provisional figures for 2017 put the amount at just over £13.9 billion.

This image about the UK’s foreign aid budget has been shared over 59,000 times at the time of writing.

In 2016, the UK provided £13.4 billion in foreign aid to developing countries. For 2017, the provisional figure is £13.9 billion.

In January 2018, a woman reported that her father had been “stuck” on a trolley at the Royal Stoke University Hospital for 36 hours. The accompanying photo was reportedly taken at the same hospital in 2015 by a different patient’s mother. We’re not able check whether this photograph is representative of the situation in hospitals across the country. But we can look into the statistics behind how long these types of waits tend to be both nationally and for individual hospital trusts.

Total health spending in England was around £125 billion in 2017/18, almost ten times higher than the foreign aid budget.

The foreign aid budget covers a different geographical area, a slightly different time period, comes from a different departmental budget, and poses very different challenges and scales.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

The UK government spent £13.9 billion on “official development assistance”, what it calls foreign aid, in 2017. That’s up 4% from just under £13.4 billion in 2016.

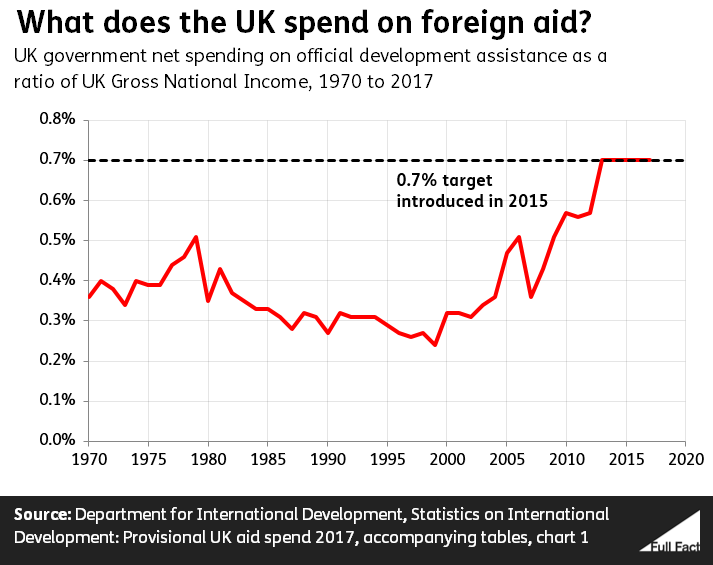

For both years, that was in line with the government’s target of spending 0.7% of the country’s Gross National Income (the annual income received by residents here plus income from overseas). That means for every £100 made here, 70p is spent by the government on foreign aid.

You can read more about where the target comes from in our explainer on foreign aid here.

This target seems unlikely to change any time soon—it’s currently enshrined in law, and although this can’t be enforced through the courts, the International Development Secretary Penny Mordaunt would have to explain herself to parliament if it wasn’t met. She recently said: “we remain committed to 0.7%”.

However, during the same speech, Ms Mordaunt proposed changing the rules on the 0.7% target so reinvested profits from private investments (she mentioned the public’s savings and pensions) could count towards it.

At the moment, only public funds are counted. She expanded on this in response to an urgent question from the Shadow International Development Secretary Kate Osamor MP, who argued that the department’s vision would “leave the most vulnerable people at the mercy of global markets”.

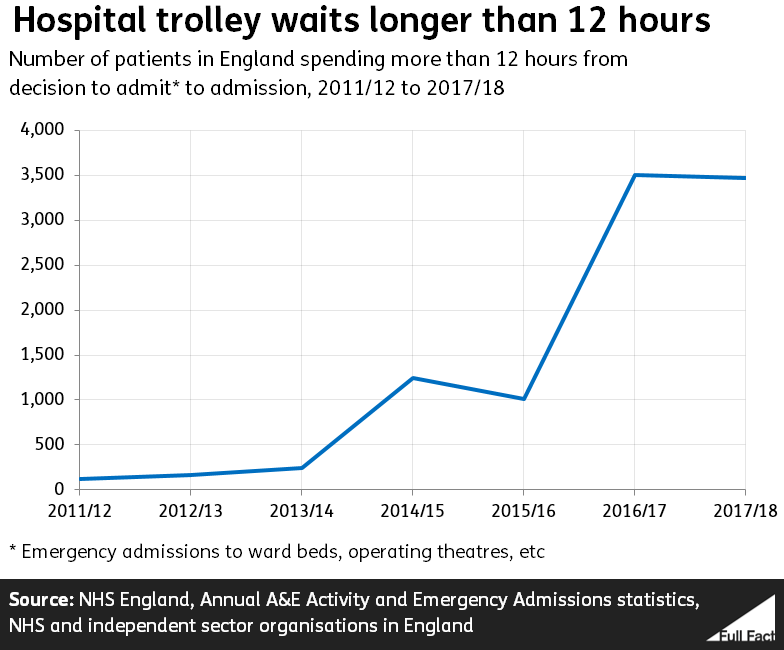

A trolley wait, as defined by NHS England, is the time from when the decision was made to admit someone to hospital, until their actual admission. Admitting them might mean they go to a bed in a ward, or an operating theatre.

In January 2018, a media outlet spoke to a member of the public who said their father had been “stuck on a trolley for 36 hours waiting to be treated”.

The NHS doesn’t break down data for trolley waits by hospital, only by NHS trust, and it only publishes data on whether waits were longer than four and 12 hours.

The Royal Stoke University Hospital is part of the University Hospitals of North Midlands (UHNM) Trust. In the three months to June 2018, there were two cases of patients having trolley waits of 12 or more hours. There were around 3,270 trolley waits of over four hours.

In the quarter before, in the three months to March 2018 (the colder season which usually has the longest A&E waits and sees most targets missed), 393 patients waited longer than 12 hours across the whole trust.

In the UK in general, around 3,500 patients waited for over 12 hours in 2017/18.

Full Fact fights for good, reliable information in the media, online, and in politics.

Bad information ruins lives. It promotes hate, damages people’s health, and hurts democracy. You deserve better.