Digitally altered Diane Abbott video

Before this election started, concerns were raised about the possibility of “deepfake” videos being deployed during the campaign.

To date, we haven’t seen any deepfakes, other than deepfakes intended to warn people about the existence of deepfakes.

However, we have seen videos that use much cruder techniques.

Today we’ve seen a video spreading online of Diane Abbott, digitally altered to show her in clown makeup, and talking about why you should vote Labour.

It’s not difficult to see that the makeup has been digitally added to the video (you can see the original unedited video here.)

It’s notable because spoof subtitles have been added to the video, which becomes interesting when you take into account that many people watch videos on social media without sound. While this obviously isn’t intended to fool anyone, it might be worth bearing in mind that subtitles don’t necessarily reflect what’s actually being said in the video.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

A&E waits: record levels—but data only goes back to 2010

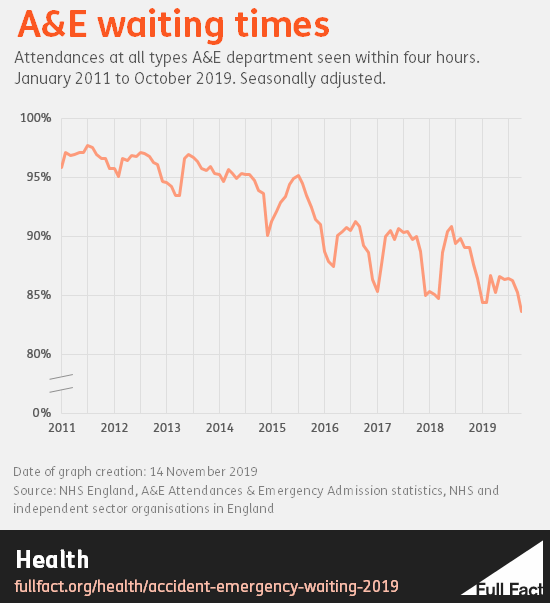

Last week many media outlets reported that A&E waiting times had hit their “worst ever level”. This is technically correct, but it’s worth noting that comparable data only goes back to 2010.

In October 2019, 83.6% of patients attending all types of A&E departments (including things like dental A&E and urgent care centres) in England were admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours.

You can read our full fact check here.

Changing tax

This morning Conservative MP Andrea Leadsom appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, and among other things discussed her party’s plans for “a proper reform of business rates”. She didn’t specify exactly what this entails, but did say “business rates is the one tax that business organisations tell us isn’t working for them”.

Presenter Nick Robinson asked her several times how the Conservatives were going to fund a reduction in business rates.

After asking for the third time “where does the money come from?”, Ms Leadsom responded:

“You’re assuming money comes from somewhere. What I’m trying to explain to you is since our reduction in the headline rate of corporation tax, the HMRC’s tax take has actually increased by something like 45% because more businesses comply”.

Ms Leadsom did not go as far as to say a reform of business rates would be funded through a reduction in corporation tax, but she did suggest that lowering corporation tax was a way of potentially generating more revenue for the government.

A couple of hours later, Boris Johnson announced that the Conservatives would postpone their proposed further cuts in corporation tax, saying that this would free up £6 billion for the NHS.

Those slightly contradictory messages aside, it’s far from clear how far corporation tax reductions have increased tax revenue overall.

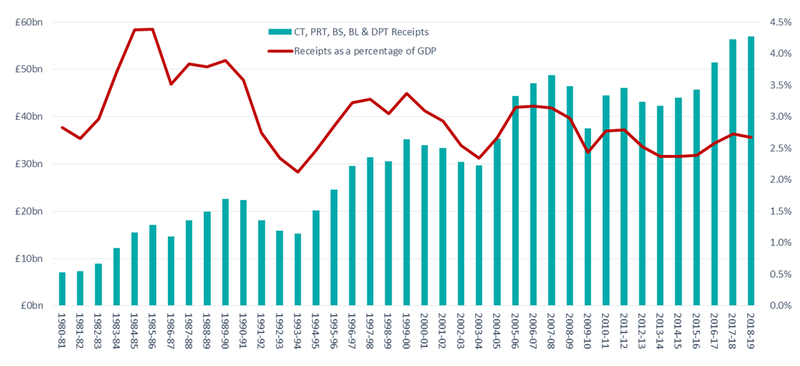

The government began reducing corporation tax at the start of 2011/12. Corporation tax revenues fell over the next couple of years, but then have increased in every year since 2014/15. They haven’t gone up by 45% in that period, though. They have increased by around 45% since 2009/10, but that was two years before the Conservatives started to reduce corporation tax, when tax revenues were at a low in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis.

And revenues as a percentage of GDP have remained fairly flat over the past decade (and are relatively low by historic standards), as you can see on this helpful chart from HMRC’s tax receipts document.

There’s no way to definitively know how corporation tax reductions might have impacted other tax revenues (such as income tax), or to what extent they may have contributed more broadly to economic growth.

As we said last time we wrote about this, "the exact impacts on economic growth are hard to predict", although HMRC's estimates suggested that the previous corporation tax cuts could result in between 0.6% and 0.8% growth in GDP over 20 years.

A routine check-up of Labour’s dental claims

Labour has announced it wants to scrap certain dentistry charges if it wins the election, which would make it free to get a check-up and get other basic services. These “band one” charges currently cost £22.70.

Jeremy Corbyn trailed the policy yesterday saying one in five patients delay going to the dentist because of cost, leaving 100,000 people in hospital with preventable problems with their teeth.

The one in five figure is significantly out of date, and it’s misleading to directly link dental costs to 100,000 hospital admissions, as he does.

The one in five claim is what the Adult Dental Health Survey found in late 2009/10. 19% of respondents in England, Wales and Northern Ireland said they had delayed dental treatment at some point in the past because of the cost.

Why such out of date figures? That survey only happens every 10 years, so it means we can’t be certain Labour’s “one in five” figure is still accurate in 2019.

Just over 100,000 hospital admissions in England in 2018/19 were related to tooth decay, and another 17,000 to gum disease. These aren’t necessarily all different people, as one person can have multiple admissions for similar ailments.

It’s misleading for Jeremy Corbyn to connect all these cases directly to people not being able to afford dental care, as he does in his tweet. This isn’t substantiated by the data, which can’t tell us the circumstances behind those admissions to hospital.

Labour's claim on NHS overtime: a plausible estimate

On Friday, the Guardian reported Labour Party research which found that “NHS staff are working over a million hours a week of unpaid overtime”.

The findings are based on data from the NHS staff survey, the most recent edition of which was published in February 2019, and Labour shared their calculations with us.

Based on what we’ve seen, it’s very much plausible that staff typically work a million hours of unpaid overtime a week collectively, but the data doesn’t show it definitively. These million hours would be spread between hundreds of thousands of NHS staff working a number of hours overtime per week.

The most recent NHS staff survey went out to over 1.1 million staff across 300 NHS organisations in England. Nearly 500,000 staff took part between October and December 2018.

Almost 463,000 staff responded to the question “On average, how many additional UNPAID hours do you work per week for this organisation, over and above your contracted hours?”

42% said 0 hours, 44% said up to 5 hours, 10% said 6-10 hours, and 4% said 11 or more hours.

If you assume that staff typically worked the average amount of overtime within the range they selected (so 8 hours for those who answered 6-10 hours, for example), this comes to roughly 1.1 million hours of unpaid overtime a week.

But that’s a broad-brush assumption and we can’t be certain that’s the case. If you were more cautious and assumed staff worked at the lower end of those ranges, it would show staff working about 670,000 hours unpaid a week

Nevertheless, the data certainly suggests it’s plausible that over one million hours of unpaid overtime are worked a week.

It’s also important to remember that this survey was answered by 46% of the 1.1 million staff to whom it was sent out (and of those who answered, 93% answered the unpaid overtime question). So it won’t reveal the full extent of unpaid overtime within the NHS in England.

We also don’t know whether those who answered the survey are representative of the rest of the wider NHS, or whether they did significantly more, or less, unpaid overtime than others.

Conservatives repeat inaccurate claim on Labour’s immigration policy

Speaking on the BBC’s Andrew Marr show this morning, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab twice repeated the claim that Labour wants “open door immigration not just from Europe but from the rest of the world” and that it “would double the overall level of immigration”.

As we fact checked this week, this claim is not credible. Labour hasn’t published its manifesto yet and details are currently expected to be released in a few days. Jeremy Corbyn has signalled in recent interviews with the BBC, including later on in today’s Andrew Marr show, that the party’s priority is to secure free movement for people who have family with settled status in the UK.

In addition, there’s no evidence that the figures the Conservatives have put on Labour’s hypothetical policy are realistic.

Who's Scot a job?

On Tuesday a Scottish government account tweeted that Scotland’s youth unemployment rate “fell by 0.3 percentage points over the year”.

This is looking at a dataset which is less reliable than the usual statistics on youth unemployment—which actually show that youth unemployment has risen in the last year.

The UK Statistics Authority has today asked the Scottish government to make it clear that the data it used is not considered reliable.

You can read our full fact check here.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Barclay’s Premier League: Is football coming home after Brexit?

Last season, for the first time in history, the finals of Europe’s top two club competitions were contested by teams from a single country—England, with the scorers including an Egyptian, a Spaniard, a Nigerian, a Frenchman and two Belgians.

So you wouldn’t exactly think that English football was struggling due to a lack of international talent.

However, yesterday Brexit secretary Steve Barclay tweeted a video claiming that, because the UK will have more control over immigration policy post-Brexit, this will mean we have more say as to where we recruit Premier League footballers from.

In the video he says we will be able to recruit players “on talent, rather than it being because they’re in Europe as opposed to the rest of the world.”

Players from the European Economic Area (EEA) can work in England with no restriction under EU freedom of movement laws, while non-EEA players have to get a work permit predicated on getting an endorsement from the FA.

The FA gives endorsements out based on whether a non-EU player plays enough for their international side, and takes into account the value of the player and wages offered.

Mr Barclay’s comments drew some confusion, because it’s not EU rules that restrict the talent pool for Premier League clubs, but the UK’s own laws restricting visas to non-EU players.

However Mr Barclay also said in the video that, alongside the desire to recruit the most talented international players, there’s also the interest (especially from the FA) to develop homegrown talent.

And here he may have more of a point. Because there are basically no restrictions on recruiting EU players, that’s had the effect of decreasing the proportion of domestic players playing at the highest level in recent decades. That (in part) led the FA to decide to impose restrictive criteria for granting visas to non-EU overseas players.

In a post-Brexit situation where EU Freedom of Movement rules no longer applied, the UK could potentially loosen visa requirements on non-EU players and increase them on EU players, meaning talent is drawn to the Premier League across the world more evenly, while retaining or even expanding opportunity for homegrown players.

Of maggots in orange juice (and other gross things)

If you've been paying attention to the news this election, there's a good chance you'll have heard a Labour politician mentioning maggots in orange juice. But what is the truth? Will we all be drinking maggot-laden orange juice post-Brexit?

But suggesting that the US "allows" a certain number of maggots in orange juice is a misreading of the US regulations—they set levels at which enforcement actions must be taken, but that doesn't mean that levels below that are absolutely hunky-dory.

The UK, by contrast, doesn't have any level at which enforcement becomes mandatory. So under the same reading, you could claim that the UK technically allows an infinite number of maggots in its orange juice. That would be daft, of course: it's just that the two regulatory systems work in slightly different ways.

The other point, of course, is that food standards often focus their attention on food safety: contaminants in food that could actually cause health issues. That's what the debate around food standards is based on. But maggots in your breakfast orange juice wouldn't actually be dangerous; they're just disgusting.

We should also note, in fairness, that when we wrote about this issue before, we also carelessly used the phrase "acceptable levels" to refer to these mandatory enforcement levels, so we probably can't be too judgey. But let's all agree to not say it again.

SNP GDP: TBC

At the SNP's election campaign launch last week, Nicola Sturgeon said that Scotland leaving the customs union and single market “will cost every person in Scotland £1,600.”

This is another one of those claims that's based on a real figure, but one that's had the uncertainty stripped away... and has then been stretched to the point of being misleading.

It’s based on Scottish government analysis which estimates that post-Brexit, if the UK is outside of the EU’s single market and customs union, Scotland’s GDP would be 6% lower in 2030 than it would have been had the UK stayed in the EU. That doesn’t mean the economy shrinks by 6%—just that it’s expected to grow by 6% less than it otherwise would have. And even that figure is pretty uncertain.

The £1,600 per person then comes from simply dividing that amount of GDP reduction by the population of Scotland.

But you can’t say that slower GDP growth will cost every person £1,600: GDP isn’t evenly distributed among everybody, and personal income is affected by a lot more than GDP.

We've written this up in a full-length fact check, which you can read here.