How the UK Health Security Agency’s misleading data fuelled a global vaccine myth

On 21 October, Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro delivered a live address through his Facebook, Instagram and YouTube accounts, which between them have tens of millions of followers. He wanted to talk to his country about the Covid-19 vaccines, and he had various print-outs ready on his desk.

President Bolsonaro is an extremely divisive figure, who has been fact checked many times. But this was only “information” he said, from “official UK government reports”. He also read from a blog that used the UK data. “I’m only relaying the news,” he said, as translated by Brazil’s news agency. “‘Official UK government reports suggest that those totally vaccinated […] are developing acquired immunodeficiency syndrome a lot faster than expected.’ I recommend you to read the article.” Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is better known as AIDS.

This claim was and is entirely false, and was quickly fact checked in Brazil. But like so much misinformation, it had roots in real evidence, which others had twisted out of shape. In this case, the president’s suggestion that the vaccines were linked with AIDS appears to have been based on a false article written in England.

And this article in turn was built on a misleading technicality in data that was first published six weeks earlier, by Public Health England (PHE)—now succeeded by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA)—as part of its weekly ‘Vaccine Surveillance Report’. We’ve not been able to see the full video, which was removed by social media companies and is no longer available online. But according to a screenshot posted by the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, and by the Desmentindo Bolsonaro Twitter account, which campaigns against Bolsonaro, at one point the president even had a print-out of the UKHSA’s weekly report in his hands.

The main source of the confusion is known by some as the “denominator problem”—and despite repeated warnings from Full Fact and others in the media, it was not until last week that the UKHSA significantly amended the report.

While Bolsonaro’s speech is a striking example of the UKHSA’s confusing data being misused, it’s far from an isolated one. A snapshot analysis by Full Fact has identified posts on Facebook and Twitter in 11 different languages, appearing to come from at least 13 different countries, that directly shared links to the PHE and UKHSA reports and made misleading claims based on the denominator problem.

This problem has gone global. And it might all have been avoided.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

How it began

At the beginning of September, ITV’s political editor Robert Peston announced that he had Covid. He was double-vaccinated, but as others were already discovering, this was not enough to guarantee not catching the disease, even if it did make serious illness much less likely.

A few days later, intrigued to see how rare his situation was, Mr Peston looked at newly published PHE data, and found that he wasn’t rare at all. Indeed, in a tweet and an article, he reproduced a table of PHE’s figures, which showed an even higher rate of Covid cases among fully vaccinated people aged 40-79 than among the unvaccinated—apparently the opposite of what the vaccines were supposed to do.

Mr Peston did not draw this comparison himself. He just said: “I was surprised by what looks like high prevalence among the double vaxxed.” And: “I am surprised these statistics have received so little attention and have occasioned so little debate.” This would not last for long.

On the same day that Mr Peston tweeted about it, an Italian member of parliament shared the PHE report on Facebook, suggesting it raised questions about the vaccines’ effectiveness. Two days later it was shared by an international lockdown-sceptic group, who also said it cast doubt on the vaccines’ value in preventing transmission. Two days after that, it was reported in Hungarian, and widely shared by a national tabloid using some of Mr Peston’s quotes—even though, by then, he had partly clarified his comments to stress that he was “wholeheartedly in favour of vaccination”.

Was the data actually wrong?

The trouble with PHE’s numbers was that, while they weren’t wrong exactly, they were seriously misleading—a problem we often encounter as fact checkers. The BBC’s More or Less programme offered an explanation on 15 September, Professor David Spiegelhalter—a leading figure in statistical communication—and the Royal Statistical Society’s Anthony Masters wrote about it in the Guardian on 19 September, and we published our own fact check the following day.

The problem itself is not particularly complicated, but it will take three paragraphs to explain.

Essentially, in order to know how often vaccinated or unvaccinated people test positive for Covid, you need to know how many in each group test positive and how many there are in each group in total. We know how many people have been vaccinated, because we count them as the vaccinations happen. But we don’t know exactly how many unvaccinated people remain, because that depends on knowing what the whole population was to start with, which has to be estimated.

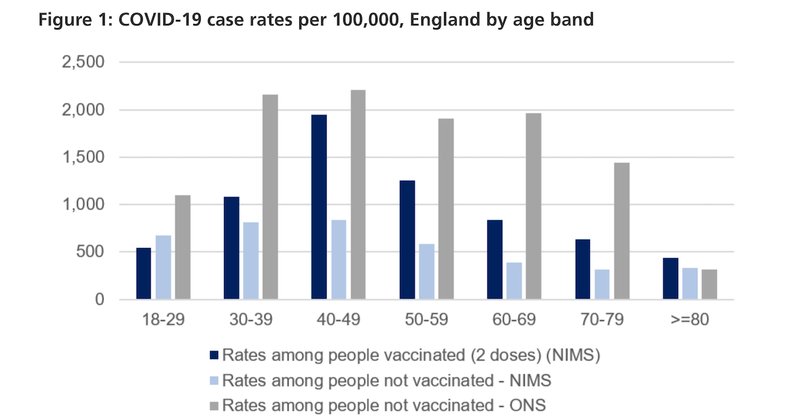

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) produces regular estimates of the English population, and the National Immunisation Management System (NIMS) has its own, based on GP registrations. However, these estimates are different, and the apparent rate of Covid among unvaccinated people changes dramatically, depending on which one you use as the ‘denominator’ in the calculation.

In our first fact check, we found that the NIMS estimate suggested that about 3.52 million people aged 40-79 were entirely unvaccinated up to 16 September, but the ONS estimate suggested only 1.35 million—a huge difference. Both estimates have strengths and limitations, but PHE used NIMS, even though, as the Office for Statistics Regulation concluded this week, its estimates “almost certainly overcount the eligible population, and so lead to large systematic biases in the case rates in the unvaccinated groups”. That choice more than halves the apparent rate of Covid among unvaccinated 40-79-year-olds, compared with using ONS estimates instead. And this effect is large enough to make it look—superficially—like people who didn’t get the vaccine are less likely to get Covid.

The effect is clear in a blog that the Office for Statistics Regulation published on 2 November. The difference between using ONS and NIMS estimates is the difference between the grey and the light blue bars in the chart below.

PHE and the UKHSA might have chosen not to publish an unvaccinated rate at all, because it simply isn’t a number that can be calculated accurately. And we do already have other data that addresses vaccine effectiveness specifically, which shows that vaccinated people are substantially (though not perfectly) protected against catching Covid.

Of course, the appearance of a lower rate of Covid among unvaccinated people may not all be down to the use of NIMS population estimates. It is conceivable that vaccinated people feel safer, and therefore take more risks. It is conceivable that they are more likely to get tested. So it is conceivable, despite being more protected, that they are also more likely to test positive, if they really are tested and exposed more often.

However, we don’t know this, so it would be a mistake to say that the UKHSA data suggests it—particularly when the population problems cast such doubt over the whole thing.

How it all got worse

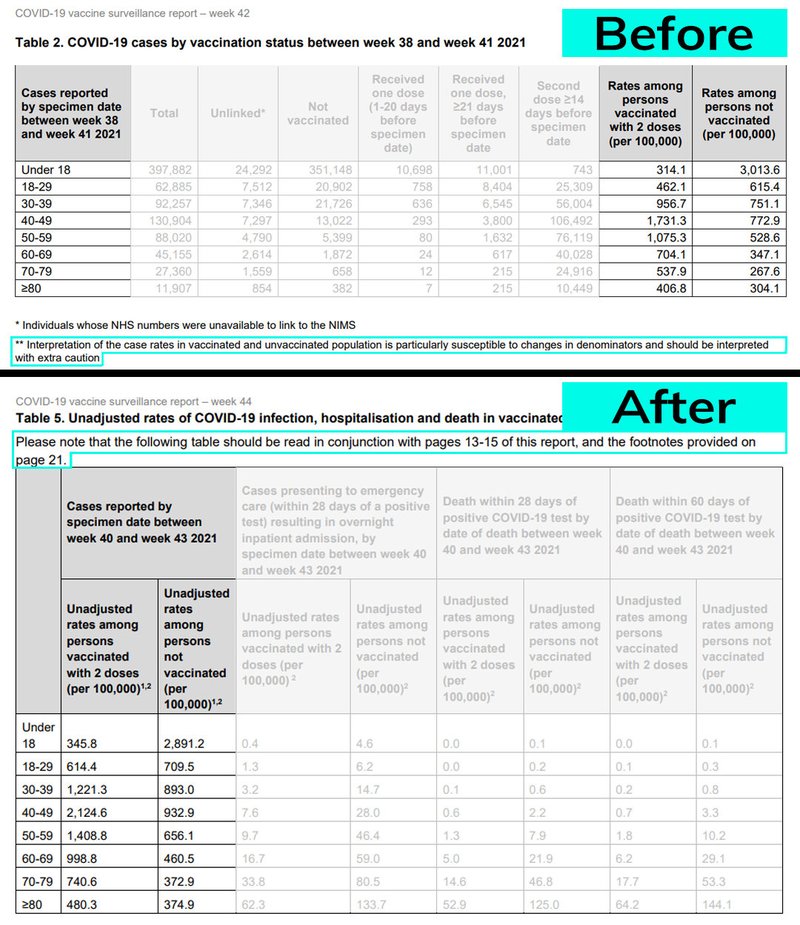

The Vaccine Surveillance Report warned when this data first appeared that it was “not the most appropriate measure to assess vaccine effectiveness”. In the second week, it also added a footnote beneath the data itself. This said: “Interpretation of the case rates in vaccinated and unvaccinated population is particularly susceptible to changes in denominators and should be interpreted with extra caution.”

It may not have been clear to everyone what this meant. It certainly seemed to make little difference. That week, and in the weeks that followed, the report was frequently misreported or misunderstood in the same way on Facebook, not just in the UK, but in Canada and Australia, by groups such as Re-start Life in Belgium and Moms for Medical Freedom in the US, and by a campaigning lawyer in Poland.

From 10 September onwards, The Daily Sceptic, a website founded by the journalist Toby Young, also attempted to calculate estimates of “vaccine effectiveness” using the data. In simple terms, this was supposed to show how much smaller (or larger) the risk of catching Covid was for vaccinated people. Its first article prompted our first fact check on the problem.

The data also came to the attention of the Exposé, formerly the Daily Exposé, a regular source of misinformation during the pandemic, whose false or misleading articles we have checked several times. Like the Daily Sceptic, the Exposé began to publish flawed “effectiveness” estimates based on the data from 1 October, and soon added its own interpretation of the numbers.

In an article “by a concerned reader” published on 10 October, the Exposé used the data to claim that the vaccines not only failed to protect people against Covid, but made them more likely to catch it because they “progressively damage the immune system”—an effect it said was similar to “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”, ie, AIDS.

The Exposé published another similar article on 15 October. The headline read: “A comparison of official Government reports suggest the Fully Vaccinated are developing Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome much faster than anticipated”. These words may be familiar from President Bolsonaro’s speech.

Each week, the Exposé published a new article with the new data, saying the same thing. These too spread around the world, through social media accounts as far apart as Canada and Sweden. It was also translated.

Not enough was done

PHE was abolished, as planned, at the beginning of October. Its vaccine surveillance work was taken over by a new body, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), which made no immediate changes to the case data in the weekly report.

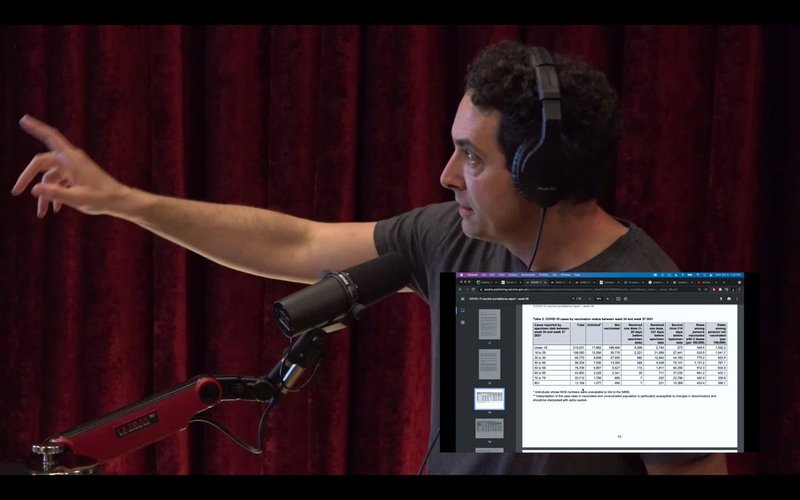

On 12 October, the US journalist Alex Berenson, who was suspended from Twitter after posting misinformation about vaccines, misused the data in the same way in front of an audience of millions on the Joe Rogan podcast—with PHE’s footnote unmentioned beside him on the screen.

In response, we wrote another fact check, because the problem clearly wasn’t going away.

Throughout this time, we and others pleaded with PHE and then the UKHSA to act. We wrote suggesting that the report be changed, perhaps by including more visible notes on the charts or tables, on 24 September, and followed up on 5 October, when we were told our concerns had been passed to the authors of the report. We followed up again on 20 October, when we also rang. The Financial Times published a detailed analysis on 11 October, and received a limited response from the UKHSA on 14 October following the Joe Rogan podcast.

And the most extreme abuse of the data was still to come.

In the hands of the president

We don’t know exactly how President Bolsonaro came to be reading out a blog from an English website. We do know that his video was soon taken down by Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, and the controversy was widely covered all over the world.

Brazil’s news agency later reported that President Bolsonaro said the information he’d cited came from an article in the magazine Exame. However, while Exame had run an article about vaccines and HIV, it seems unrelated to the UK data the president mentioned.

A source we know the president did use—because he can be seen holding up a print-out from it in the video—is a blogpost from a website called Before It’s News. This blogpost directly cites The Exposé and essentially copies the Exposé article of 15 October. Portuguese versions of that Exposé article had also been published before the president’s address. (This endless copying and recopying of online misinformation is common. David Icke’s website has also published a summary of the same article.)

The Brazilian newspaper Estadão and Brazilian fact checkers Aos Fatos also traced the source of Bolsonaro’s AIDS claim through Before It’s News to the Exposé.

How the UKHSA finally responded

Sir David Norgrove, who is chair of the UK Statistics Authority, has said he is “lost for words” at the way that PHE and UKHSA published its Vaccine Surveillance Report, and called the numbers “misleading and wrong”. And on 28 October, under increasing pressure, UKHSA finally changed its presentation of the data. Then on 4 November, it changed the presentation again.

Look at it now, and you’ll find longer caveats explaining the denominator problem and the limitations of the data across multiple pages, with the case rates combined in a separate table, along with hospitalisation and death rates. There is now a note above the table advising that it should be “read in conjunction” with the relevant notes. The word “unadjusted” has also been added to the case rate columns, along with numbers indicating footnotes.

Speaking about the first set of changes, Dr Mary Ramsay, UKHSA head of immunisation, told the Financial Times that there had been “some misunderstanding and, at times, deliberate manipulation of the data presented”.

In a blog on 2 November, she also said: “To make our data less susceptible to misinterpretation, the UK Health Security Agency has worked with the UK Statistics Authority to update some of the data tables and descriptions in the report, specifically around rates of infection in vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.”

It isn’t clear at this stage how effectively this will deter people from misusing the figures. The Financial Times quotes Professor David Spiegelhalter saying that the effects of the first changes “will be minor compared to the gross distortions produced by using incorrect population figures… Some footnote warnings cannot compensate for calculating such hopelessly biased rates.”

After the UKHSA’s latest changes, Professor Spiegelhalter told us: "Regardless of their warnings, I am disappointed that they are still calculating case-rates for unvaccinated people when we know, due to their use of NIMS, that these rates are generally unrealistically low."

The Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) has said that while it welcomed the first changes, which represented “considerable improvements to the presentation of the data”, it thought there was still “considerable room for further improvement.”

Following the second changes, it told us: "These further changes are positive, but we think there is still more that the UKHSA could do. In our letter on 1 November, we suggested some ways of setting out the uncertainties more clearly, such as by publishing the rates per 100,000 using both denominators, and making clear in the table, perhaps through formatting, that the column showing case rates in unvaccinated people is of particular concern."

We could see that the amended report was still being misused after the recent changes. After both reports, the Exposé simply continued publishing the same sort of analysis as before, although it cut the end of the table away from the rest of the data. (This removed section shows lower rates of hospitalisation and death among vaccinated people). And after the first set of changes the data was still being used without its caveats by Dr Clare Craig, a pathologist and member of the Health Advisory and Recovery Team (HART), a campaigning group whose comments have previously been the subject of our fact checks.

What next?

We have asked the UKHSA a series of detailed questions about its presentation of case rate data and its approach to misinformation, but at the time of writing it has not directly answered any of them. It only sent us a link to Dr Ramsay’s blog.

The UKHSA may only be the publisher of the data, but it does have to take responsibility for at least the foreseeable ways that its work could be misused. In publishing the data it did, in the way it did, and by not fixing the problem for so long despite being told that it was giving rise to misinformation, the UKHSA made it easier for some people to misunderstand the effect of the vaccines, and for others to use the authority of UK data to mislead people.

This isn’t good enough. Any official body which becomes aware that its data is being commonly used as a vector for misinformation—particularly during a pandemic—has a responsibility to act promptly to fix the problem. We asked the UKHSA to publish a statement addressing the issue, and to clarify the meaning of its data on social media, both of which it has now done. (It recently published a thread on Twitter). But we still think it needs to do much more to address the problem—for example, by considering the Office for Statistics Regulation’s detailed suggestions for further improvement on how the data is presented. It is crucial that the UKHSA keeps a close eye on how its data is being used and shared over the coming weeks.

We will have to wait and see whether the recent changes to the UKHSA report will prevent more people around the world from believing falsehoods about the Covid vaccines. But they are likely to come too late for many of the people who believe them already.

Thanks to Aos Fatos and Lupa for their help on the research for this article.