Spending on the NHS in England

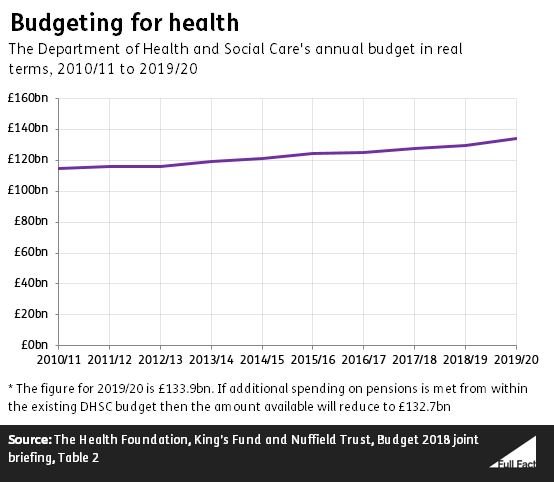

Total health spending in England was around £129 billion in 2018/19 and is expected to rise to nearly £134 billion by 2019/20, taking inflation into account.

In 2018/19 around £115 billion was spent on the NHS England budget. The rest was spent by the Department of Health on things like public health initiatives, education, training, and infrastructure (including IT and building new hospitals).

Last year the government announced that an additional £20.5 billion in real terms will be made available for the NHS in England by 2023/24—though it’s unclear how much money will be spent on health overall.

At the time health experts said this money will “help stem further decline in the health service, but it’s simply not enough to address the fundamental challenges facing the NHS, or fund essential improvements to services that are flagging.”

The NHS is facing severe financial pressures, with trusts across the country spending more than they’re bringing in. The NHS was also asked several years ago to find £22 billion in savings by 2020, in order to keep up with rising demand and an ageing population.

Health experts from the Nuffield Trust, Health Foundation and King’s Fund say tight spending in recent years and increasing demand for services have been “taking a mounting toll on patient care”. They add that there is “growing evidence that access to some treatments is being rationed and that quality of care in some services is being diluted.”

The £20 billion of additional funding for the NHS in England will be spread out over the five years to 2023/24. When it was announced this meant an average increase on the NHS’s budget of around 3.4% a year, taking inflation into account. But inflation over the next few years is now set to be higher than expected, meaning the actual real terms increase will be less than that.

In January 2019 the National Audit Office (NAO) said that “Spending in [areas of the Department of Health’s budget aside from the NHS] could affect the NHS’s ability to deliver the priorities of the long-term plan, especially if funding for these areas reduces. It also said “There is a risk that the NHS will be unable to use the extra funding optimally because of staff shortages.”

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

What’s happened to NHS spending in recent years?

In 2013, NHS England said it faced a funding gap of £30 billion by the end of the decade, even if government spending kept up in line with inflation. So it needed that much more to deliver care to a growing and ageing population, assuming it made no savings itself.

A year later the NHS laid out plans for how it might handle this gap. One ambitious option was that the NHS itself would find £22 billion in savings, leaving the other £8 billion to be filled by the government.

The Conservatives said in their 2015 election manifesto they would provide that £8 billion in government, and expect the other £22 billion in savings from the NHS. The Nuffield Trust, writing in our election report, said this still left unanswered questions on funding:

“£8bn is the bare minimum to maintain existing standards of care for a growing and ageing population …

“improving productivity on this scale [£22 billion] would be unprecedented”

The new Conservative government followed through on the commitment and started claiming it was giving £10 billion, giving the NHS what it asked for, and more.

In their 2017 election manifesto, the Conservatives said they would increase NHS spending by at least £8 billion in real terms over the next five years, and increase funding per head of the population for the duration of the parliament.

In 2017 the think tanks said there would be a £4 billion gap in health spending in 2018/19 alone, but the £1.9 billion provided by the government at the end of last year meant that “around half of the minimum gap we calculated has been filled.”

They said even based on the government’s current spending plans there is likely to be a spending gap of over £20 billion by 2022/23.

To mark the 70th birthday of the NHS in 2018 the Prime Minister announced that funding for the NHS in England would be increased by £20.5 billion by 2023/24, or by an average of 3.4% per year.

This was welcomed by the think tanks and others like the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), who have said that the money will allow the NHS to “help stem further decline in the health service”. But they said that increases of at least 4% a year on average are needed in order to meet the NHS’s needs and see any improvement in its services.

NHS providers are in deficit

About 47% of NHS trusts—which provide secondary care to patients who’ve been referred there by a GP—were in the red in 2018/19. The figure was 67% just among acute hospital trusts—which make up the bulk of NHS trusts across England.

Collectively they finished 2018/19 with a deficit of around £571 million.

All though a larger proportion of trusts are in deficit than the year before (when it was 44%), the size of the deficit has fallen—in 2017/18 the overall deficit was £960 million.

But if you account for the one off savings the NHS made in the year, temporary extra funding and accounting adjustments, then the underlying deficit of these trusts is around £5 billion. That’s an increase on the year before. The Nuffield Trust has said “While it is true more money is coming into the health service in the year that has just started, this boils down to just £1bn extra for NHS trusts. That leaves them dependent on continued short term one off cost cuts and emergency funds: an impossible basis on which to plan a stable recovery.

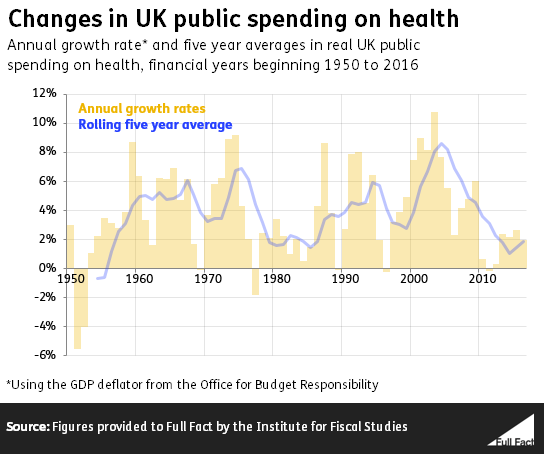

UK-wide spending has been rising long-term, but more slowly in recent years

Looking at the wider UK, the amount spent on health has been increasing over the long-term. That’s true whether it’s expressed in cash, cash adjusted for inflation, per person, or as a proportion of the size of the economy. All those trends show spending stalling or falling slightly in the years after 2010/11—at the same time as most other departments saw reductions in spending—and picking up again in more recent years.

Health spending grew at an average annual rate of about 3.7% from 1950/51 up to 2016/17, accounting for inflation. Public spending on health usually increases year on year, and there are only a handful of times in the last 60 years when it hasn’t.

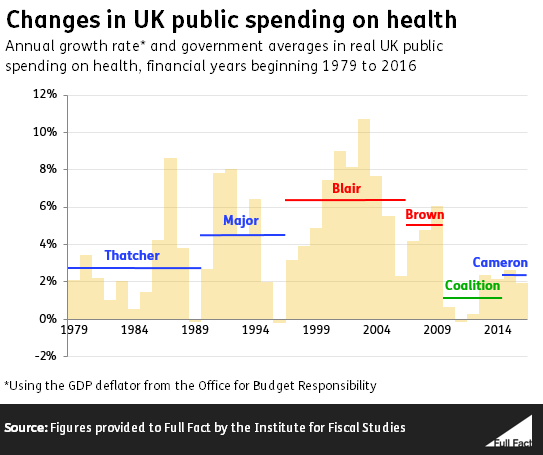

We can also look at the level of UK health spending year on year when successive governments were in office. Health spending is devolved so the UK government is only responsible for health spending in England (though changes in health spending may affect the overall budgets of the devolved governments).

The average growth between 2009/10 and 2014/15 under the Coalition government was 1.1% and from then to 2016/17 under the Conservative government was 2.3%.

At the moment, UK public health spending is the equivalent of about 7% of GDP, similar to what it was back in 2010 and higher than in previous years. Back in 1955, it was worth about 3% of GDP.

Demand for health services has also increased over time. Adjusting the same figures above to account for the population, the average annual growth in per person spending between 1949/50 and 2016/17 was about 3.3%, and was 0.6% between 2009/10 and 2016/17.