King of the swingers: will the UK general election be decided by 200,000 voters in marginal seats?

Like some lost tribe, somewhere there exists a group of just 200,000 swing voters, who, after weeks of party campaigns the length and breadth of the country, will alone decide the fate of the nation.

Or so we're often told.

But where has this idea come from? And more importantly, how credible is the claim that such a small percentage of the electorate will really decide who gets to move into Number 10?

We've found that a group of this size could influence the election, but they'd be difficult to track down in advance.

On the hunt for the 200,000

Like other lost tribes, we find that repeated mention of its existence has helped cement this claim's credibility.

It's a claim that's been around since at least 2001, but seems to re-appear around election time, for example in 2008 and 2010. The claim has also surfaced in the media in the build-up to this election.

The figure of 200,000 voters in marginal seats was mentioned by the Green Party in their manifesto, while the SNP manifesto talks of small numbers of swing voters in marginal seats. The Liberal Democrats, UKIP and Plaid Cymru also allude to electoral reform in their manifestos for 2015.

The definition of 'marginal' doesn't appear to be set. Some organisations focus on seats where a swing of 5% would change the result. But choosing different assumptions could change the outcomes: there's nothing special about a 5% swing.

Breaking down the numbers

In the 2010 general election, 45.6 million UK citizens registered cast 29.7 million valid votes. How could just 200,000 votes change the results? The logic comes from targeting a small number of voters in the most tightly contested constituencies and assuming they changed their vote to the next largest party instead.

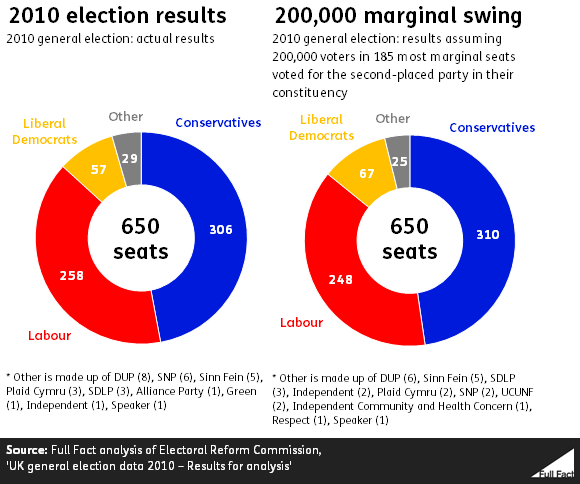

Looking back at the results in 2010, just 200,000 people voting differently could have changed the outcome in 185 of the most marginal constituencies. This would have resulted in the election of 185 different MPs from those chosen. It sounds like this would drastically alter the result.

Swing seats swing both ways

But just as a swing in one constituency might improve the fortunes of one party, a swing the other way elsewhere can just as easily negate it.

For example, those 185 seats in 2010 that could have changed hands. Overall, 53 seats would have changed hands from Conservative to Labour, but 55 seats would have gone the other way, from Labour to Conservative. Similar gains and losses would have happened for other parties, so the effects are smaller than suggested by the figure of 185 seats with different results.

But what if?

It's tempting to see what could happen under more extreme assumptions, where we look only at the most marginal Conservative seats. If 200,000 Conservative voters in those seats had instead voted for the party that came second, then 118 seats could have changed hands, enough to give Labour an overall majority.

But a similar thing could have happened in the past, assuming a swing against Labour in the 2005 general election, where Labour won a comfortable majority. If 200,000 Labour voters in the most narrowly-won Labour seats had switched to the party which came second, then 128 seats could have changed hands, enough to give the Conservatives more seats than Labour.

Impossible to identify

While it's easy enough to identify voters who could have changed the outcome in past elections, it's all but impossible to identify them in order to canvass them ahead of an upcoming election. And much as those belonging to a lost tribe might move from place to place, just who these 200,000 voters are and in which constituency they live changes each election.

The last three elections show this clearly. Assuming 200,000 people switched from the first to the second placed party, 185 seats could have changed in 2010, and 177 seats in 2005. But only 76 of these were marginal seats in both elections. If you include the vote in 2001, 30 constituencies were marginal in all three elections. It isn't necessarily the case that the same group of powerful voters consistently decides the outcome of the election, and that everyone else is consistently ignored.

In fact, about 350 different constituencies could be considered marginal by our definition in at least one of the previous three elections, over half of the total number nationwide. This ignores boundary changes, which have changed the size and shape of constituencies over time.

Pollsters often focus on the areas where the race looks closest, but ultimately it's not possible to know exactly how close results will be until after all votes are counted. It's like looking back at a crucial moment in a football match and saying that those few seconds were the ones that decided the match. Easy to do afterwards, but hard to predict in advance.

Targeting those here and now

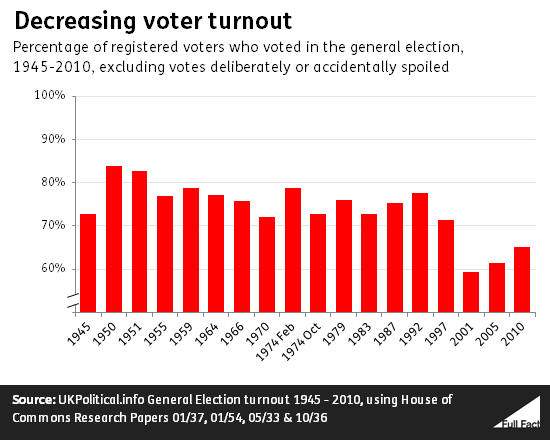

Another angle on this debate is voter turnout. Small changes in voter turnout could have effects every bit as dramatic as the changes from our group of 200,000 mystery voters.

In 2010, the general election turnout was 65%. We investigated the effect of upping turnout in each constituency by 5%: that takes overall turnout to 70%. That's still below 74%, the average UK turnout since the Second World War. Assuming that each of these additional voters opted for the second-placed party, 152 seats could have been decided differently. In fact, in 30 seats, an increase in turnout of just one percentage point could have been enough to change the result.

It's interesting to see that in an electorate of over 45 million, the composition of Parliament can come down to the votes of just a small number of people.

While parties often have a good idea which constituencies are their key 'battlegrounds', it's much harder to know who exactly the key voters will turn out to be.