A post on Facebook claims to show the difference between what each EU country will pay into the EU budget, and what it will get back in spending from the EU, in 2022. It has been shared over 3,000 times.

The post is inaccurate in a number of ways.

Most fundamentally, it’s misleading to use 2018 data to show what budget contributions will be in 2022. The EU budget has not been finalised for the period 2021-2027 yet, and it is being planned on the assumption that the UK won’t be part of it. So we can’t know what the UK’s contributions would look like in 2022 if it stayed in the EU.

In addition, many of the numbers contained in the post are incorrect.

The post says that in 2018 the UK paid £11.02 billion into the EU budget, and received £6.09 billion back in EU spending. It includes a link to its source, which takes you to this page from the European Parliament’s website.

The UK figures on that website aren’t quite the same as what’s in the graphic, although they’re not very far out. However the EU’s figures are in euros, not pounds, and for 2017, rather than 2018.

In 2017, the UK paid around €13.8 billion (£12 billion based on the average exchange rate for 2017) into the EU budget including VAT contributions and received roughly €6.3 billion (£5.5 billion) of EU spending.

For 2018, the UK was set to pay €18 billion (£16 billion) into the EU budget, but we don’t know yet how much it will get back in EU spending.

These figures differ slightly from those published by the UK government, which we have also used in the past. The differences are relatively slight, and come down to different methods of accounting.

We can’t know what the UK would pay into the EU’s budget in 2022

Using these figures, the post tries to work out what the UK’s contribution will be in 2022, while making clear it is using 2018 figures. It does this by taking the UK’s latest net contribution to the EU (what it pays in to the budget minus what it gets back in spending), and then adding in the cost of the UK’s current rebate or ‘discount’ on budget payments, which it assumes the UK will no longer get by 2022.

Its approach is flawed for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, there’s no way to know how accurate predictions about future budget contributions will be, using current contributions as a starting point. The EU sets its budgets in multi-year cycles, with the next budget set to run from 2021-27. That budget hasn’t been published yet, and the EU doesn’t plan to include the UK in it—so we can’t know what the UK’s contribution would be in 2022 if, hypothetically, the UK were still an EU member by then.

You probably could use existing contributions to make a rough guess as to what the budget might look like in 2022 (the UK would almost certainly still be one of the biggest contributors to the EU budget), but it’s misleading to present these numbers so definitively.

A second problem is that the post assumes that, if we stay in the EU, our contributions will go up because we will lose our “rebate” after 2020 or 2022. This can’t be known either.

The UK (along with some other EU countries) currently gets a rebate which reduces its annual contributions to the EU budget. This was worth €4.9 billion in 2017 (£4.3 billion)—reducing our contribution by 32%.

It is correct that the EU wants to get rid of all rebates over the course of the next EU budget (which runs from 2021 until 2027), but it’s not clear that it would happen by 2022. The UK could potentially block the change if it was still in the EU.

Luxembourg does not get back 3000% more than what it pays in

The post also attempts to calculate the “return on investment” for each country paying into the EU budget.

This is trying to show the difference between what each country pays in to the EU budget, and what it gets back in EU spending. It claims that this ranges from Luxembourg getting back over 3000% more than it pays in, to the UK getting back 62% less.

There are a number of problems here. As explained above, this excludes the UK’s rebate from the calculation, and figures for today can’t be used as a prediction for payments in 2022. It also says the data is for 2018, whereas the EU has only published full figures up to 2017, and some of the figures in post are quite inaccurate (we’ll get onto that).

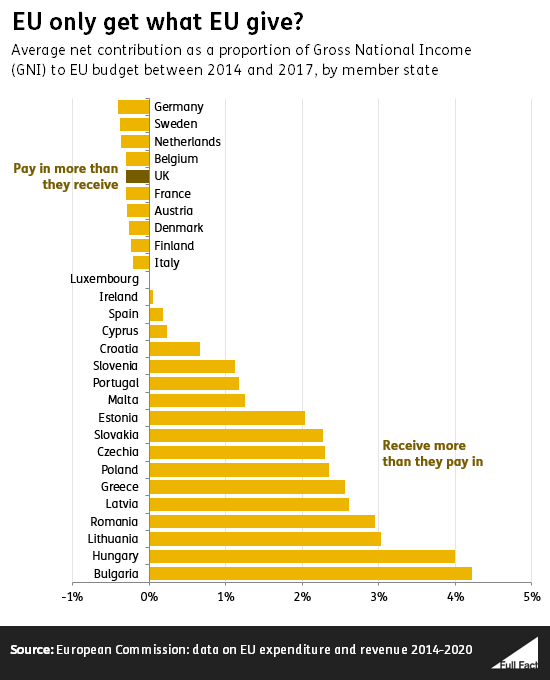

That said, the overall trend is fairly accurate. Some countries do get back significantly more than others, and the UK is one of the biggest “net contributors” meaning it pays in more than it gets back. Richer countries are typically contributors and poorer countries are typically beneficiaries. The UK has been the third or fourth largest contributing country to the EU budget in recent years, along with Germany, France, and Italy.

However, some of the numbers in the table are wildly inaccurate. For example, it says that Luxembourg contributes £45 million per year to the EU budget, whereas it contributed almost six times this much (around £287 million) in 2017. It’s not clear how the post has calculated “returns on investment”, but Luxembourg doesn’t get anything like 3,000% more back in spending than it pays in.

Something else to consider is that the biggest net contributors (Germany, France, and the UK) have much bigger economies than the biggest net beneficiaries. If we look at contributions as a percentage of countries’ Gross National Income, the differences are far less stark.

It shows that the UK’s net payments into the EU budget are worth around 0.3% of its gross national income, and Germany makes the biggest contributions—worth 0.41% of their national income.

Likewise, the biggest net receipt a country has received as a percentage of its national income is 4.2% (Bulgaria).