Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“I’m pleased to say that what we’ve seen under this government is nearly half a million more disabled people actually in the workplace.”

Theresa May, 2 November 2016

This is correct, comparing now with 2013, although arguably “this government” came into power after the 2015 election.

The number of people in the UK officially classified as disabled and in employment has increased from 3.3 million around the time the Conservative government entered office in 2015 to 3.4 million in April to June this year.

Over the same time the number of people reporting that they had a physical or mental health condition or illness which would last more than 12 months and who were in employment increased from 7.1 million to 7.2 million.

The government told us that the Prime Minister was referring to the increased number of disabled people in work since April-June 2013, when the Coalition government was in power. At this time there were 2.9 million disabled people in work. Using this figure the number has indeed increased by just under half a million.

Why 2013? That’s as far back as comparable figures go, due to changes in how the figures were put together.

These figures don’t give an idea of how many disabled people have entered the workforce or left it. They only show how much the total number has changed over time.

The Prime Minister made her comment in response to Jeremy Corbyn asking what evidence there was that “imposing poverty on people with disabilities actually helps them into work?”

The estimated proportion of disabled people in relative poverty, after housing costs, has increased by 2% since 2010/11. However, there are several other measures of poverty, and on these the proportion of disabled people affected has either fallen or remained flat since 2010.

“This week, Mr Speaker, Oxford University studies found that there’s a direct link between rising levels of benefit sanctions and rising demand for food banks. A million people accessed a food bank last year and received a food parcel, only 40,000 did so in 2010”.

Jeremy Corbyn, 2 November 2016

We looked at the Oxford study last week. Mr Corbyn gives a fair account of its findings.

There’s no single estimate of all people using food banks in the UK. Labour told us that Mr Corbyn’s figures come from the Trussell Trust, a charity which gave out 1.1 million food packs last year. It was 40,000 in 2009/10.

The Trust’s figures count the number of emergency food packs, not the number of people. It says that on average people need two packs per year, so the number of individual people using its services is likely around 550,000.

It’s difficult to compare these numbers over time because the number of food banks has also increased. More people have access to a food bank now than in 2010, so these figures alone can’t tell us about demand.

The Trust says that the number of people they helped last year grew faster than the number of new food banks.

Trussell Trust food banks account for around half of all food banks in the UK, according to a 2014 estimate. So their figures can’t tell us how many people are receiving emergency food in total, but a million individuals is plausible if half of food banks served half a million people.

“Mr Speaker, the Housing Benefit bill has gone up by more than £4 billion because of high levels of rent and the necessity of supporting people in that.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 2 November 2016

“If he thinks that the amount of money being spent on Housing Benefit is so important, why did he oppose the changes we made to Housing Benefit to reduce the Housing Benefit bill?”

Theresa May, 2 November 2016

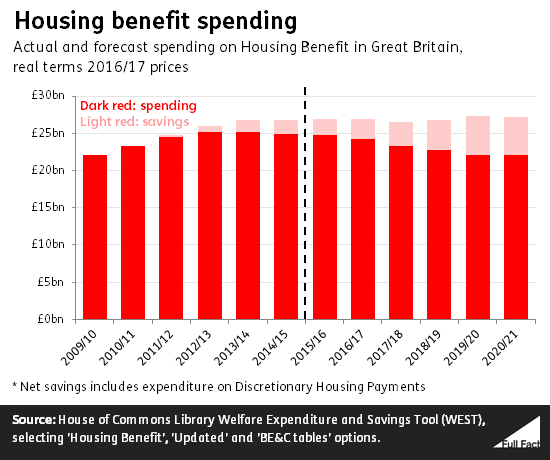

Mr Corbyn is correct on his raw figures. The Housing Benefit bill did rise from around £20 billion in 2009/10 to over £24 billion in 2014/15, according to the Department for Work and Pensions. Spending for the last financial year hasn’t been confirmed, but is expected to be around the same.

This is without adjusting for inflation, though. In real terms the increase is more like £2.3 billion rather than £4.3 billion.

Housing Benefit is around 14-15% of total benefit expenditure.

Although the increase is at least partly down to a rise in the number of people getting it, the amount paid out per person has also risen slightly. If we divide real terms expenditure by caseload, it comes to just over £5,000 per recipient in 2014/15, where it had been £4,900 in 2009/10. (This crude average doesn’t tell us anything about what individuals typically receive.)

But Mrs May is right that the bill is set to fall. Policy changes since 2010 are due to realise real terms savings of over £5 billion by 2020/21, according to analysis by the House of Commons Library. While spending will still be higher than in 2010 in cash terms, it’ll be down after adjusting for inflation, assuming the forecasts are correct.

He said today, in response to Mrs May, that “my concern [is]... the incredible amount of money being paid into the private rented sector [because of] excessive rents”.

"The UK [is] the only country in the EU with no time limit on detention"

Gavin Newlands MP, 2 November 2016

It’s correct that there’s no time limit in the UK on how long someone can be detained under immigration rules, unlike in any other EU country.

Most EU countries have to follow the so-called Return Directive, which says immigration detention cannot normally last longer than six months. That doesn’t apply in the UK and Ireland. In many countries, including Ireland, the usual limit is lower anyway.

But while there’s no explicit limit, this doesn’t mean people can be held indefinitely. Ever since a court ruling in 1983, there’s been an assumption that the state has limited powers to detain anyway. For example, detention can’t last more than what’s “reasonable” given the circumstances. The contents of this ruling have come to be used and known as the ‘Hardial Singh’ principles (after the name of the case).

That said, independent inspectors found a few years ago the application of ‘a reasonable period’ of time was inconsistent, and a group of MPs found similar cases when it gathered evidence on the practice.

The government says the protections already in place, and the fact that Parliament recently rejected a longer limit, mean a change to the rules on limits isn’t necessary, and has confirmed recently it isn’t seeking any change to the law.

How does all this play out in reality? Almost two thirds of people leaving detention in the past year were detained for less than 29 days. 3% were detained for over six months. As of 30 June, one person had been detained for over three years.

“Mr Speaker, according to Sheffield Hallam University study, one in five claimants that have been sanctioned became homeless as a result of it.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 2 November 2016

This is missing an important caveat.

The study that Jeremy Corbyn is referring to only looked at people who were using homelessness services. The proportion of people who lose their job after being sanctioned is likely to be smaller than this—even though the report he’s referring to does suggest a link between welfare sanctions and becoming homeless.

What are sanctions?

People are offered welfare payments on certain conditions, such as spending a certain amount of time looking for a job. They can be sanctioned with a reduction in their payments if they don’t comply. Payments can also be stopped altogether. Sanctions have been more widely used in recent years, especially since 2012.

What did the survey say?

The report he’s referring to interviewed 548 people using homelessness services who were receiving welfare between February and April 2015. It found that 213 of them had been sanctioned in the previous year, so about 39%.

About half of the people who had been sanctioned said that it made it harder to keep their home.

45 said they lost their home as a result of a sanction. That’s about a fifth of the 213 who had been sanctioned, and that’s where the figure comes from.

Since the survey invited responses from people using homelessness services, it’s likely that a smaller proportion of all people who are sanctioned then become homeless.

But the report suggests a link.