Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“When hospitals are struggling to provide essential care why is the government cutting the number of beds in our National Health Service?”

Jeremy Corbyn, 22 February 2017

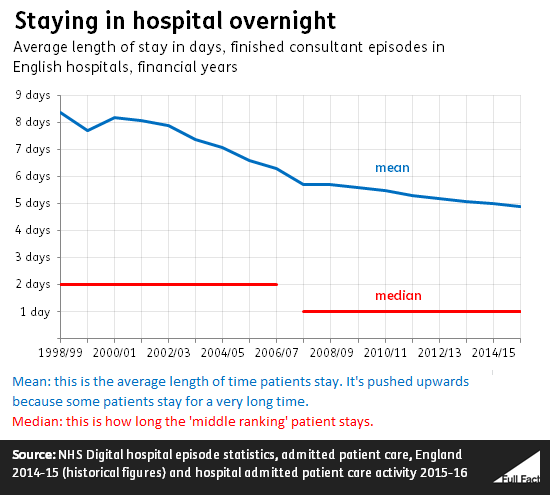

“Thanks to medical advances, to the use of technology, to the quality of care, what we see in hospital stays is actually that the average length of time for staying in hospital has virtually halved since the year 2000. But let us look at Labour’s record on this issue, in the last six years of the last Labour government, 25,000 hospital beds were cut”

Theresa May, 22 February 2017

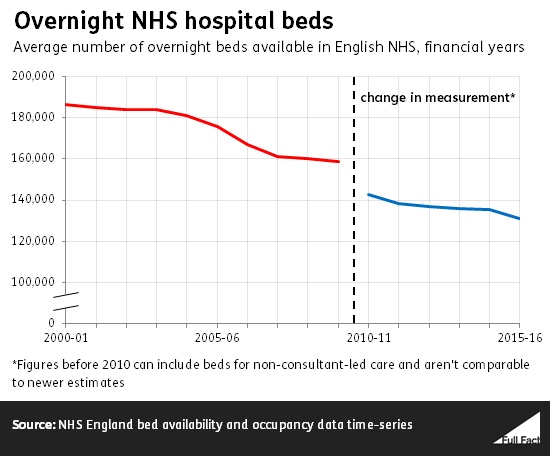

The number of hospital beds has been falling over the past decade, regardless of who was in office.

The total number of overnight hospital beds in the English NHS has actually been falling almost constantly since the 1980s. It fell by about 26,000 in the last six years of the most recent Labour government as Mrs May says, and it’s still falling now as Mr Corbyn says.

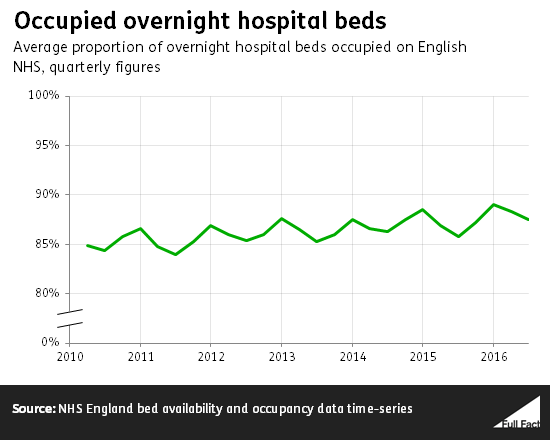

The proportion of beds that are occupied has been rising slowly since 2010. From July to September last year the proportion hit 87.5% — the highest recorded figure for that time of year. That’s higher than the safe level of 85% recommended by NHS Providers and the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

“The Royal College of Midwives estimates there is a shortage of 3,500 midwives in England.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 22 February 2017

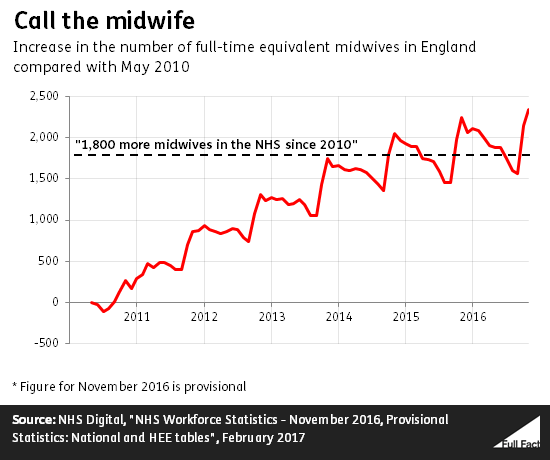

“We have 1,800 more midwives in the NHS since 2010.”

Theresa May, 22 February 2017

As so often, these two seemingly incompatible takes on the state of midwifery are both correct—so much so that the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) endorses both.

The RCM, a trade union for pregnancy specialists, published its annual State of Maternity Services report on 6 February.

It notes the “good news” that there were the equivalent of 1,600 more full-time midwives in England by September 2016 compared to May 2010. That’s correct according to NHS Digital. Mrs May said 1,800, but the difference is neither here nor there—there are considerable fluctuations from month to month. The rise between May 2010 and May 2016 was around 1,900.

But, the RCM cautions, the profession is aging, with “one in three midwives in England… now in their 50s or 60s”. The number of midwives aged under 50 has actually fallen since 2010. This, too, we’ve verified against the official data.

And the RCM says that as the number of births and the age profile of pregnant women rises, more midwives are needed: “our current calculation is that the NHS in England is short of the equivalent of around 3,500 full-time midwives”.

The report doesn’t say what this calculation is exactly. The RCM told us that it involves taking the number of live births in England for 2015, and dividing it by the number of births that a full-time midwife can handle per year. (This is 29.5 per year in most cases, a number described by the National Audit Office as a “widely recognised benchmark”.)

That gives a total for the number of midwives that are needed, which is then upped by 9% “to account for specialist and managerial posts”. That can be compared to the number of midwives actually in post.

The RCM notes that this is “only an estimate and we do not want to give a false impression of precision”, adding that it came up with this approach with the help of a “midwifery-specific workforce planning tool” called Birthrate Plus.

Nursing training places

From this August new nursing, midwifery and allied health professional students from England will no longer be given an NHS bursary, but will instead apply for student loans.

It’s not the case that 10,000 new places are already available as the Prime Minister claimed. The government has said that the policy change means up to 10,000 more training places could be offered by 2020. This is because the number of places universities offer will no longer be capped by the number of bursaries funded. We don’t know how many of these will be on nursing courses.

It’s also incorrect that 10,000 fewer places on nursing courses have been filled. This widely reported figure refers to the drop in applications from England, not places filled. Applications from students in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, who aren’t affected by the changes, fell by much smaller amounts.

We don’t know yet how many nursing places will be filled this year—the January deadline for applications has just passed and courses won’t start until September this year.

Not everyone who applies is accepted, and not everyone goes on to work as a nurse in the NHS. Last year 44,000 English students applied and 23,000 were accepted. Some will leave their course or work outside the NHS.

114,000 places on nursing and midwifery courses between 2012 and 2016 will give the equivalent of 84,000 nurses and midwives in the NHS by 2020, according to Health Education England estimates.

“Nine out of 10 NHS trusts are unsafe”.

Jeremy Corbyn, 22 February 2017

“I have to say to the Right Honourable Gentleman that he should consider correcting the record because 54% of hospital trusts are considered good or outstanding, quite different from the figure that he has shown”.

Theresa May, 22 February 2017

Mr Corbyn was referring to research by the BBC which found that 137 of the 152 hospital trusts in England had more than the recommended number of beds occupied between 1 December 2016 and 22 January 2017. That does work out as nine out of 10 trusts.

Hospitals are meant to try and ensure no more than 85% of their beds are occupied at any one time. "There is strong evidence that bed occupancy rates above 85% can compromise patient safety, increasing the risk of infection”, according to the chief executive of NHS Providers, Chris Hopson.

The BBC explained its analysis to us and it seems reasonable. It calculates occupancy per weekday, per trust. It’s possible to do that using the published figures although we haven’t had time to verify them exactly.

There were only three days between 1 December and 22 January when the percentage of beds occupied across the whole of England fell below 85%, according to analysis by the King’s Fund, a health think tank.

The Department of Health told us that the Prime Minister was referring to the results of inspections carried out by the Care Quality Commission, the watchdog for health and social care.

It rated 56% of core hospital services across NHS acute trusts in England as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ as of July 2016. The CQC says this is “the level at which patients most directly experience the quality of care being delivered”. That falls to 32% when you look at the individual ratings for acute trusts and all services provided by them.

We’ve asked the Department of Health if it’s core hospital services the Prime Minister is referring to.

These are two quite different ways of assessing hospital standards.

The CQC told us that while it does look at figures like the bed occupancy ones Mr Corbyn was quoting before it inspects a hospital, they won’t inform the result of its inspection. For example, if a hospital had consistently high bed occupancy rates, this issue would be looked at during an inspection. But it would only be reflected in the final result for the hospital if inspectors thought it was concerning during their visit.

Having said that, the CQC does mention high bed occupancy rates in its overall assessment of the state of health in England, but this was only one of a number of factors it said were “challenging” the system.