Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“Last week the government sneaked out a decision to overrule a court decision to extend Personal Independence Payments to people with severe mental health conditions. [This government] seems unable to find the money to support 160,000 people with debilitating mental health conditions.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 1 March 2017

“...this is not a policy change, this is not a cut in the amount that is going to be spent on disability benefits and no one is going to see a reduction in their benefits from that previously awarded by the DWP.”

Theresa May, 1 March 2017

Two recent tribunal decisions widened the interpretation of Personal Independence Payments (PIP) legislation.

Over 160,000 people might have seen their PIP payments go up because of the tribunal decisions—or become entitled to them—according to estimates from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

They won’t now that the government has amended the legislation.

Mr Corbyn is quoting the DWP’s estimates fairly and Mrs May is broadly right that people won’t see their payments reduced because of the amendment (compared to what they are now).

But a relatively small number of people who were assessed after the Tribunal decisions on 28 November may see their payments fall, as and when they are next reassessed. We don’t know how many, and the DWP told us that it hasn’t published estimates.

And there’s more than one way to interpret the government’s move.

The government says that the amendments are designed to “restore the original aim of the benefit”, focusing support on those who need it most.

Critics say that the government is “shifting the goalposts”.

There’s a second set of questions about whether the government followed the right process when it put through the amended legislation.

Critics say that the government was wrong to bypass the Social Security Advisory Committee, which is supposed to be consulted on changes to social security regulations.

But the Secretary of State can bypass the Committee if he or she thinks that it’s a matter of urgency.

The government says it was right to push through the amendment fast to avoid inconsistencies in how PIP claims are assessed.

What did the courts rule on PIP?

Court decisions last year mean that more people would have got the disability benefit PIP, or a higher amount of it. An argument over the reasons behind these decisions dominated Prime Minister’s Questions today:

“The court ruled that the payment should be made because the people who are going to benefit from it were suffering overwhelming psychological distress.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 1 March 2017

“What the court said is that the regulations were unclear.”

Theresa May, 1 March 2017

The court in question is the Upper Tribunal. It made two decisions in November 2016, the effect of which the government is now reversing with new PIP regulations. That’s expected to affect people with mental health conditions in particular.

In making the first decision, Upper Tribunal Judge Mesher said that it “illustrates once again the gaps left in the drafting of [the original PIP regulations], requiring a large expenditure of effort to render its provisions coherent”. And in the second, three judges pointed to “a difference of opinion within the Upper Tribunal” on what the regulations mean.

So Ms May is correct in that sense. The regulations (introduced by the Coalition government) are ambiguous enough that even judges struggle to apply them consistently to real-life cases.

The second of these decisions was about “overwhelming psychological distress”, and how this related to someone’s ability to “follow the route” of a familiar or unfamiliar journey. This isn’t a phrase that the judges introduced. It’s from the original PIP regulations.

For example, people are awarded four points towards their entitlement to PIP if they need “prompting to be able to undertake any journey to avoid overwhelming psychological distress”.

There are also scores of 10 for those who can’t “follow the route of an unfamiliar journey” without assistance, and 12 for those who can’t “follow the route of a familiar journey” without assistance. You need at least 8 points to get this part of PIP at the standard rate, and 12 for the enhanced rate.

What the Upper Tribunal had to decide was whether the regulations allowed for someone being unable to “follow the route” of a journey because of overwhelming psychological distress.

The government had argued that such distress couldn’t be considered for the purposes of these particular scores. It said they were focused on “sensory or cognitive impairment”.

The Upper Tribunal rejected this argument, saying that the government had been correct to concede the point in a prior case. It reasoned that someone might be overtaken by psychological distress while trying to follow a route, if he or she didn’t have assistance.

That means someone might be entitled to four, 10 or 12 points because of psychological distress—which the tribunal thought was fine: “there is no reason why there should not be an overlap”.

The judgment was a highly technical analysis of the language and logic behind these regulations.

"By 2020 [the government] will have borrowed more and increased the national debt by the total borrowing of all Labour governments."

Jeremy Corbyn, 1 March 2017

This is correct in one sense, but it’s not a fair comparison.

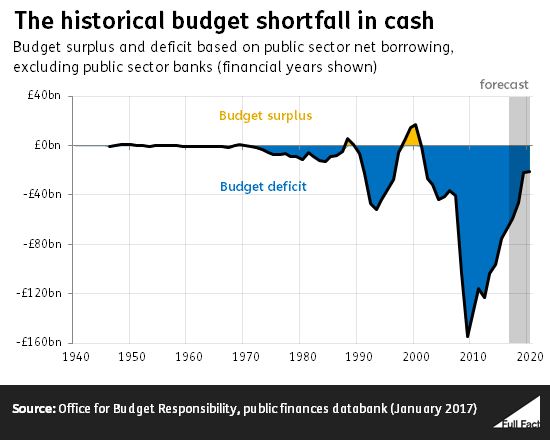

It’s right if you add up the expected budget deficit from 2010 to 2020, including both the Coalition and the Conservative government.

That comes to some £870 billion. This is well over the combined borrowing of Labour governments since 1945, around £490 billion.

This isn’t actually very surprising, for two reasons.

The first is that borrowing has been historically high in recent years following the financial crisis in the late noughties, when Labour was still in office. Borrowing rose from £40 billion in 2007/08 to a peak of £155 billion in 2009/10.

A new government can’t wipe out that level of borrowing overnight, nor would it necessarily want to. You can argue the deficit should or could have come down quicker anyway, but simple arithmetic like this clearly doesn’t give you the whole story.

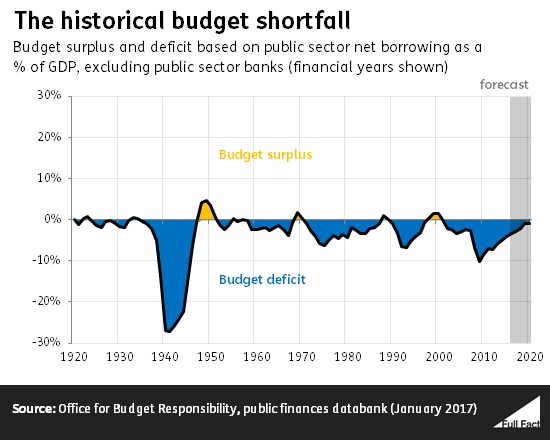

Secondly, the economy is much bigger now than it used to be. Once you look at all these figures compared to the size of the UK economy, the picture is different.

Borrowing peaked at about 10% of the size of the economy (GDP) in 2009/10, and it’s now down to about 3.5%. That’s a relatively large deficit, but not off the scale historically.

The Labour governments of Harold Wilson and James Callaghan ran deficits of around 5% of GDP back in the 1970s, for example. The post-war Labour government in 1945 borrowed 15% of GDP in its first year.

“It is this Conservative government that has introduced parity of esteem in relation to dealing with mental health in the National Health Service.”

Theresa May, 1 March 2017

‘Parity of esteem’ in the NHS means that patients should be able to access services which treat both mental and physical health conditions equally and to the same standard.

The aim for equality between physical and mental health was something that was included in the Coalition’s mental health strategy in 2011, recognised in the Health and Social Care Act 2012, and the NHS Constitution in 2015 after the Conservative government came to office. The idea is something that has been talked about for decades.

The Coalition government also produced a plan for achieving parity of esteem by 2020.

The Prime Minister’s office told us that she was referring to the government’s policy of parity of esteem more broadly, rather than any specific action it has taken. That said, her statement could be misinterpreted to mean that the government has now achieved parity of esteem, which many experts have said is not the case.

The independent Mental Health Taskforce said last year that despite a number of steps there was “not yet parity between an individual’s rights to physical and mental health care”.

This year it said that there’s a lot to be optimistic about in mental health and that the “infrastructure needed to sustain change has been put in place”, but it’s a long-term project.

The King's Fund, a health think tank, has said recently that mental health services need “greater parity of funding”. A committee of MPs has also said that NHS budget pressures and the need for more planning to ensure the right workforce is in place are making it difficult to achieve equality.