Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“Between 2015 and 2018 there’ll be a real-terms cut in central government funding to police forces of £330 million.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 29 March 2017

“What we’ve done in the [Comprehensive Spending Review] is actually protected that police budget [...] we have protected those police budgets, including of course the precept that they are able to raise locally.”

Theresa May, 29 March 2017

The two party leaders are talking about slightly different things here. Both have a point—the local “precept” for police funding in England and Wales that Mrs May referred to is the key to understanding why.

Police funding from central government is going to be cut in real terms over the next few years—1.4% between 2015/16 and 2019/20, according to the government’s own figures.

Mr Corbyn’s claim covers a shorter timeframe and a slightly narrower definition of central government funding, according to calculations provided by his office.

We’ve checked these and got almost exactly the same results as Labour: this amount is set to go from £7.6 billion in 2015/16 to £7.5 billion in 2017/18. That’s a reduction of £0.33 billion (or £330 million) once expected inflation is factored in.

But a good chunk of police funding is raised through local taxation on top of what central government provides. The government assumes that all local Police and Crime Commissioners will raise the maximum from this precept that they’re allowed to.

If they do, then police funding overall will remain flat in real terms over the course of the parliament.

“1.8 million more children in good or outstanding schools.”

Theresa May, 29 March 2017

There were 1.8 million more pupils in good or outstanding rated schools in England as of August 2016 compared to August 2010.

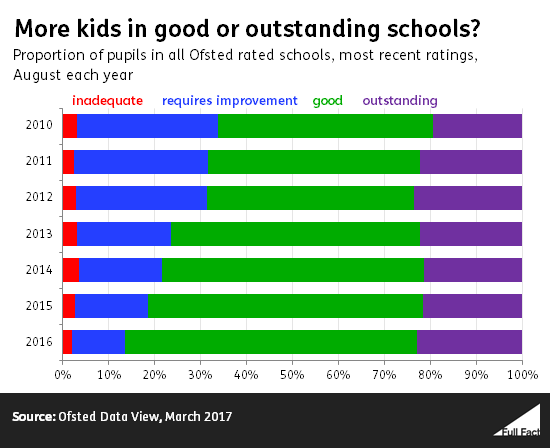

The total number of pupils has increased every year since 2009, but the proportion of pupils in good or outstanding schools has also increased. 86% of pupils were in one in August 2016, compared to 66% in August 2010.

23% of pupils were in schools rated ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted, 64% ‘good’, 11% ‘requires improvement’ and 2% ‘inadequate’.

Most of the changes in ratings are in the middle two categories, ‘good’ and ‘requires improvement’. The proportion of pupils in ‘good’ schools has mostly risen, and the proportion of pupils in ‘requires improvement’ schools has fallen every year.

There have been much smaller changes in the proportion of pupils in ‘outstanding’ or ‘inadequate’ schools, which have risen and fallen a little each year.

Ofsted says schools’ performance is improving.

Improvements in primary schools have been concentrated in deprived areas and those with poor schools. However, the proportion of children in good or outstanding primary schools ranges from 100% in some areas to 69% in the Isle of Wight.

In secondary schools the gap between the North and Midlands and London and the South East has widened. There’s also much wider variation between areas at secondary than at primary, from 100% in ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ schools in some parts of London to below 50% in other parts of the country.

The results are affected by Ofsted’s inspection practices

In 2012 it changed from rating schools ‘satisfactory’ to ‘requires improvement’. The majority of secondary schools that were rated satisfactory are now good or outstanding. A fifth have since closed, with more poorly rated schools planning to close. Where they become new academies they’re not counted until the new school is inspected.

Ofsted also focuses inspections on poorly performing schools. This means areas with low rating have more opportunity to show improvement and the best ones aren’t routinely inspected. There’s a growing number of outstanding schools where that inspection took place more than nine years ago.

Since we factchecked this, new figures for March 2017 have been released. These show that there are still around 1.8 million more pupils in good or outstanding schools since 2010.

“We have protected schools budgets and we're putting record funding into schools.”

Theresa May, 29 March 2017

“[The Public Accounts Committee] say that funding per pupil is reducing in real terms and goes on to say schools' budgets will be cut by £3 billion, equivalent to 8% by 2020 […] If the Prime Minister is right then the parents are wrong, the teachers are wrong, the IFS is wrong, the National Audit Office is wrong, the Education Policy Institute is wrong, and now the Public Accounts Committee, which includes eight Conservative members in it, is also wrong.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 29 March 2017

Mrs May is correct that spending on state schools in England is at record levels and has been protected. This means that it’s increasing in line with inflation, and spending per pupil is also being maintained in cash terms.

But once inflation and rising pupil numbers are factored in together, there will actually be a per-pupil reduction in spending. This is what Mr Corbyn is talking about.

The Public Accounts Committee of MPs noted on 22 March that schools would need to make “economies and efficiency savings” of £1.1 billion in 2016/17, according to the Department for Education. These would have to reach £3 billion by 2019/20, or 8% of the total schools’ budget.

The Committee also said there would be a reduction in real-terms per-pupil spending, quoting evidence from the National Audit Office. The NAO has said that spending per-pupil will decrease by 8% between 2014/15 and 2019/20, after inflation is factored in. That’s mostly down to rising pupil numbers and increasing costs from staff wages and pension schemes.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has also said that school spending per-pupil “has been frozen in cash terms between 2015/16 and 2019/20, resulting in a real-terms cut of 6.5%”.

The Education Policy Institute, a think tank, has also said that “once inflation and other pressures are taken into account, all schools in England are likely to see real terms cuts in funding per pupil over the next three years”. It put together some projections as to how cost pressures might affect schools in the coming years, though we’ve not had time to check all these yet.

“250,000 pieces of [extremist] material have been taken down since February 2010 from the Internet.”

Theresa May, 29 March 2017

It’s the job of one particular police unit to “instigate” the removal of extremist material from the Internet where it breaches internet companies’ terms of service, or the law.

The unit’s latest figures show about 250,000 pieces of such material have been taken down since 2010.

The Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) was set up in 2010. It identifies extremist and terrorist material online.

Members of the public can also report content to be examined by the CTIRU. The Unit then asks internet companies to remove such material.

The guidance gives the following examples of terrorist or extremist content:

- Articles, images, speeches or videos that promote terrorism or encourage violence

- Content encouraging people to commit acts of terrorism

- Websites made by terrorists or extremist organisations

- Videos of terrorist attacks

As of 21 December 2016 the CTIRU said that it had taken down 249,091 pieces of extremist content since 2010. Almost half were taken down in 2016.