Broken promises? What Full Fact’s Government Tracker does (and doesn’t) tell us about Labour’s first year

As anyone who’s been following UK politics over the last year will know, after winning a convincing majority in the 2024 election Labour’s time in office has seen its popularity plummet.

The party is down in the polls as it heads to Liverpool for its annual conference, and there have been multiple media reports of supposed political missteps by the government, and several high-profile departures.

Full Fact has written fact checks about several of these issues, and Labour’s record in office more generally, when we’ve seen false or misleading claims from politicians on all sides.

But in the last year we’ve also been applying our fact checking skills in a different—and innovative—way. We launched our Government Tracker in November 2024 to monitor progress on the pledges made by Labour in its manifesto, holding the government to account for the promises it’s made but also shining a light on the information—or lack thereof—that voters need to make up their own minds on the government’s delivery.

It’s been a big piece of work. When we launched the tracker it was monitoring 43 key pledges from Labour’s manifesto. We’ve since added another 37 pledges—some from the manifesto, some not—with more on the way.

Of the 80 pledges we’ve looked at so far, 17 are currently rated as ‘achieved’—that is, in our view the government has done what it said it would do. Another 18 appear ‘on track’, and in 19 other cases we can point to signs of progress.

So with around two thirds of the pledges we’ve looked at, the government appears either to have delivered what it said it would or is making progress towards it.

Given the widespread media criticism and relatively poor polling Labour has faced of late, that may sound surprising. There are just three pledges we’ve rated as ‘appears off track’, as things stand: the government’s promises to build 1.5 million new homes in England, end the use of hotels to house asylum seekers and restore development spending to 0.7% of national income.

And at this relatively early stage in the parliament, we can point to only one promise that’s not been kept, on something of a technicality perhaps—the pledge to capitalise the National Wealth Fund with £7.3 billion. (Labour has said it will allocate funds in a way that matches the spirit but not the letter of this manifesto commitment.)

Importantly though, a further six are rated as ‘unclear or disputed’—these include the highly contentious pledge to not increase taxes on “working people”, as well as a commitment to train thousands more midwives.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The tracker’s limitations

While it’s tempting to look at the headline numbers as some sort of delivery scorecard, they come with a number of important caveats.

We’ve only examined a small sample of the many (about 300) pledges or commitments that were set out in some form in Labour’s manifesto. And in selecting those to write about first, we were guided by what Labour said its own priorities would be—its ‘first steps’ and “five missions”—which potentially means the pledges we’ve written about so far are skewed towards the things Labour was always likely to act on first.

Likewise, while we have included a number of pledges made since Labour came to office, we’ve had to be highly selective in doing so.

We’ve also had to make plenty of tricky judgement calls when it comes to assessing progress. Pledge tracking is an art, not a science—though in true Full Fact style, we set out our logic and sources on each pledge page, so if you think we’ve missed something you can let us know.

Finally, we’re constantly updating these ratings as new information comes to light, so these numbers will inevitably change over the course of the parliament, and it may be that we see many more ‘not kept’ pledges in the coming months and years.

But with all that said, for those looking for hard evidence of the government’s supposedly poor performance, our Government Tracker doesn’t provide the smoking gun some might have expected.

Our verdict on transparency? Must do better

The tracker does provide clear evidence on one area where the government needs to up its game—in providing us, and all voters, with the information we need to hold them to account.

As a charity that campaigns for transparency, trust and honesty in politics, perhaps our biggest finding so far, when we took stock in March and still today, is that for too many pledges there’s simply insufficient information available to provide a meaningful rating.

In some cases we’ve lodged multiple calls and emails with departmental press offices, or even had to submit Freedom of Information requests, to try and get the information we need to judge whether the government is delivering on its promises. It shouldn’t be this difficult—after all, if a team of fact checkers is struggling to get straight answers to basic questions, what hope does the public have?

When we did a full analysis in March, we found 12 out of the 51 pledges we’d covered at the time were difficult or impossible to meaningfully rate, due to unclear wording or insufficient information on the details of the pledge. And a further nine pledges lacked important information to determine how success should be measured.

Six months on, many of the same pledges still have us scratching our heads. Has the government kept its pledge to not increase National Insurance for “working people”? That’s disputed, given in autumn 2024, the government raised NI for employers but not employees, and as Labour’s manifesto failed to offer a clear definition of what its pledge meant, we can’t say for sure either way.

The pledge on training “thousands more” midwives is another we’ve rated as ‘unclear’—the government doesn’t appear to have answered the question “thousands more, compared to what?” As we’ve said before, manifesto commitments that are open to different interpretations are at best a recipe for confusion; at worst they fuel cynicism and disengagement.

A promise to “halve serious violent crime” also remains relatively unclear—we don’t know for sure which specific offences that pledge refers to. But we’re rating it as ‘wait and see’ for now, as we do have regular figures from police-recorded data and the Crime Survey for England and Wales which will, ultimately, show trends in the levels of some violent crimes, such as homicide.

Even where we have rated pledges as ‘achieved’, there are questions over transparency.

The government has more than met its target to deliver an extra two million NHS appointments in England per year. But in hailing the progress it's made on this pledge—the health secretary said in May there had been a “massive increase”—it has repeatedly failed to mention the rise in appointments is actually less than was seen the previous year under the Conservatives. That first became apparent after Full Fact uncovered the relevant data using the Freedom of Information Act, calling into question whether it was a meaningful promise to begin with.

What about other ways of tracking the government’s performance?

Our Government Tracker focuses largely on Labour’s manifesto commitments, though we’ve subsequently added a few promises made by ministers while they’ve been in office. But there are lots of different possible ways to measure a government’s performance—and what you’re measuring, and how, can paint a very different picture.

Some other trackers, such as those from Channel 4 News and the “independent hobby website” Pledge Progress, have taken a similar, manifesto-based approach, and, like us, at this stage can point to few fully ‘broken’ pledges. But others have taken a different approach.

The Economist’s tracker, for example, has taken data from across eight domains—immigration, income, housing, health, energy, crime, transport and the environment—then normalised every metric on a scale from zero to 100 and taken the average to produce an “overall government-performance score”. And in July Sky News similarly scrutinised metrics on key topics, such as small boat arrivals or police-recorded violent crime.

There are arguments for and against this approach, which overall may paint a more critical picture of the government’s record so far. It tells us less about the government’s delivery on specific promises, but arguably gives a better real-time insight into key measures which voters care about.

We decided to focus on the manifesto because it’s the closest thing there is to a ‘contract’ with voters—promises made by a party about what it’ll do if elected. And in advance of the election, Full Fact campaigned for those manifestos to be worded in ways that were honest, accessible and meaningful. For that reason, we’re judging the government’s performance against the way its promises were worded in its manifesto, rather than any other statement from ministers, or any alternative interpretation of what Labour ‘really’ intended to deliver, if somehow different from what it said in its manifesto.

We’ve seen a number of examples of commitments where the wording of the manifesto makes it easy for the government to demonstrate progress. Several of the pledges we’ve looked at were expressed as an intention to introduce new legislation or to conduct a review of a particular policy area.

This is entirely normal—it’s what governments do. But it is of course relatively easy to introduce a Bill to Parliament, and then for a government with a healthy majority to ensure that Bill passes and becomes an Act of Parliament, or to commission a policy review. These do not necessarily immediately lead to real-world outcomes that voters will experience as positive change.

And some things of course aren’t prefigured in a manifesto at all. Any government will always have to react to events, and this one is no exception. It will also be judged, quite naturally, on how it’s responded to a new administration in the White House, on developments in Ukraine and the Middle East, and to riots following the Southport murders last summer.

So while we’ve found that in several cases we can point to progress against exactly what was promised in its manifesto (and we applaud precision and clarity in manifestos where we see it), we’re aware that this isn’t necessarily the same as delivering the change that voters may wish to see.

In other words, it’s entirely possible that even if Labour does deliver on (most of) its manifesto commitments, it will be judged adversely by voters in the coming months and years.

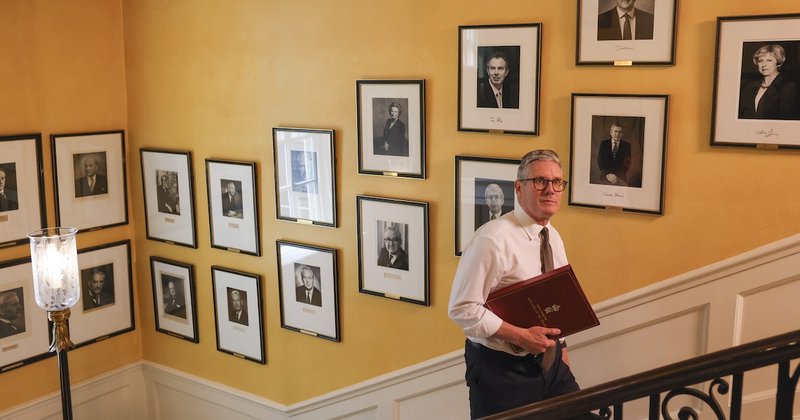

Last year, Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer made a commitment to making information publicly available, “so every single person in this country can judge our performance on actions, not words”. We agree with this sentiment, and we remind everyone who accesses our Government Tracker of this exact quote. We’ll continue to hold him to it.