BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“There was a point, a bar graph, chart within the [Brexit white] paper, that stated that UK workers were going to get 14 weeks holiday. You can imagine my office was beside themselves when they heard this, only to find out a couple of hours later that it was a misprint and it's actually 5.6 weeks.”

Rebecca Long-Bailey MP, 2 February 2017

The government published its white paper on Brexit on 2 February. This sets out the 12 priorities the government has identified for Brexit.

Later the same day it corrected one of the charts in the paper which compares the amount of annual holiday and paid maternity leave workers are entitled to under both UK law and EU law.

It was widely reported that the chart had suggested that under UK law workers get 14 weeks of paid holiday every year and that under EU law workers get just 5.6 weeks of paid maternity leave.

In fact it’s the other way round.

In the UK workers are entitled to 39 weeks of paid maternity leave compared to 14 weeks under EU law. Similarly they are entitled to 5.6 weeks holiday every year under UK law and four weeks under EU law. The graph in the white paper now shows this.

“Health tourism is allegedly stacking up a bill of over £200 million, nearly £300 million, depending on the figures you get”

David Dimbleby, 2 February 2017

“Even if we recover all of those costs it's not going to plug the hole that we have coming up in the NHS”

Maajid Nawaz, 2 February 2017

It’s correct that the estimated cost of health tourism is up to £300 million a year. Recovering all these costs will make only a small dent in the overall funding gap the NHS faces.

‘Health tourism’ usually refers to people who deliberately come to the UK to use NHS services they’re not entitled to for free, and people who take advantage of the system by frequently visiting the UK to use GP services and get prescriptions. The exact definitions can vary.

David Dimbleby is talking about estimates from a few years ago that suggested a range of £100-£300 million as the cost of deliberate health tourism, although the estimates are uncertain.

As Maajid Nawaz says, recovering all of these costs isn’t going to plug the funding gap the NHS is facing.

In 2013, NHS England said it faced a funding gap of £30 billion a year by the end of the decade. The government is putting in extra funds to cover some of that gap, although experts doubt there is enough money being committed to deal with it adequately.

The estimated costs of health tourism are about 0.3% of health spending on specific services, so savings in this area alone will make a relatively small difference.

It’s also not a simple matter to recover all the money. David Dimbleby also referred to a report out this week from the Public Accounts Committee which expressed concern over the systems the government had in place..

Part of the problem is identifying who isn’t entitled to free care and needs to be charged. The committee reported that in 2012/13, the NHS charged 65% of the amounts it could have charged to people from outside Europe and 16% of what it could have charged from those within.

“We were told there would be a punishment budget and that didn't happen. We were told that growth will collapse and that hasn't happened. Yet again the Bank of England have upped their forecast. We were told that companies would flee the country. This wasn’t just after we left the EU—this was immediately after the referendum.”

Laura Perrins, 2 February 2017

Brexit hasn’t happened yet. Most forecasts before the referendum did predict that the economy will grow more slowly once we’ve left the EU. No-one will be able to judge whether these forecasts have been proved right for some time, since the outcome will depend on whether or not the UK gets a trade agreement with the EU and how the effects play out.

The debate about whether they’re right will probably never be settled, because we’ll never know what would have happened in another world, if the UK had remained in the EU.

Ms Perrins is correct that there were also predictions of short-term problems in the immediate aftermath of the vote. These were based on a different set of assumptions about how businesses, consumers and politicians would respond to the vote, and were proved wrong.

Then-Chancellor George Osborne did say that there would have to be an “emergency budget” in the event of a vote to leave. While the public finances might yet suffer in the longer term if the forecasts are right, there was no emergency budget to shore them up. The government hasn’t stuck to its aim for a balanced budget, and now plans to run a deficit in 2020/21.

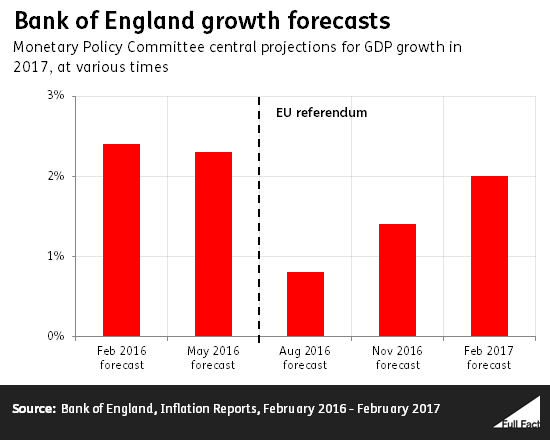

The Bank of England has a more optimistic view of the prospects for economic growth now than it did just after the referendum. It expects GDP to rise by 2% in 2017, whereas in August 2016 it said 0.8% and in November 1.4%.

But in the coming years, the Bank still expects slower growth, partly because of higher import prices caused by the drop in the value of sterling since the referendum.

When it comes to businesses “fleeing the country”, you can cherry-pick different company announcements—some positive, some negative. Individual pieces of news won’t give us a definitive picture at this stage, and estimates for foreign direct investment in 2016 won’t be published until December.

“...and even the Resolution Foundation brought out a report this week saying we were on course for the biggest increase in inequality since Thatcher.”

Rebecca Long-Bailey, 2 February 2017

That’s what the Resolution Foundation forecast in a recent report, talking specifically about income inequality. Unfortunately, you can’t factcheck the future.

But you can look at the story you’re being told and decide if you think it’s reasonable.

The report assesses what things have driven changes in incomes and wages over recent years and looks at forecasts for where those things are headed up to 2020/21. It then makes a judgement about the implications for incomes and income inequality.

Its headline prediction is that income inequality might be set to rise by more than it has in any parliament since Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister.

That’s based on a number of forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility. Those include slower growth in employment, earnings struggling to keep up with higher price inflation, tax cuts felt most by richer households and benefit cuts felt most by poorer households. It also suggests that auto-enrolment pension schemes will reduce the take-home pay of working-age households in the short term.

As the report itself adds, these are only projections.

It’s better to describe the claim as a bottom-line judgement about where the economy and public policy are likely to go, rather than a fact, and at a time when there’s plenty of uncertainty and debate about future of the economy the impact of leaving the EU, as the report acknowledges.

“Okay, but when you say 'on course', for the record, the statistics show the gap is narrowing”

David Dimbleby, 2 February 2017

That’s a fair summary of the general trend in inequality among disposable incomes over the past decade, although there’s lots of ways to look at inequality.

After increasing sharply in the 1980s, headline measures of disposable income inequality have fallen across most UK households in the last couple of decades (after taxes and benefits, and not accounting for housing costs).

That said, it matters at what point you measure household income and exactly which measure you use. It’s stayed roughly the same on some measures if you count incomes before tax and benefits or after housing costs.

And the overall movement has been the result of many of underlying trends. For example, a recent report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that although male earnings inequality had increased significantly in the last two decades, there had been a large fall in the proportion of people living in workless households, the earnings of men and women had become more equal, and pensioner incomes had grown faster than some parts of the working population. These are all meaningful changes in inequality in their own right.

The trend in inequality at the very top has been different to the trend across the bulk of the population. Although income inequality has generally fallen, the share of income that goes to the very richest households has continued to rise, and that’s been reflected in the public interest about the incomes of the top 1%.

Since the statistics vary from year to year, and the general downward trend is gradual, it’s hard to give a definitive judgement how any of these trends have changed under the coalition and the most recent Conservative government.