The facts behind Labour and Conservative Facebook ads in this election

If there’s one issue that dominated discussion of campaign techniques in the run up to this election, it was the topic of online adverts. How would they be used? Would they contain misinformation? Would the UK be deluged with a torrent of “dark ads”?

As the campaign draws to a close, we can start to answer at least some of those questions.

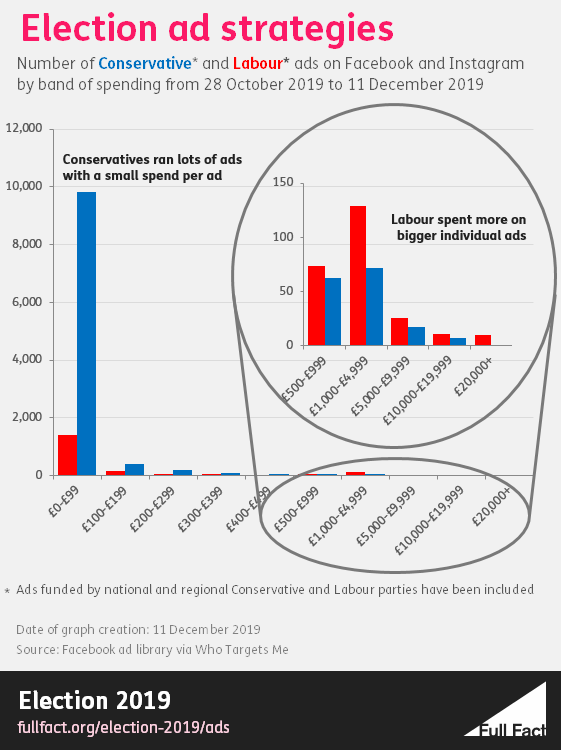

Most notable is that the Conservatives and Labour have had markedly different approaches to their use of Facebook ads during the election.

The Conservatives have focused on adverts that include many of their key election pledges and attack lines (many of which include fact checkable claims) and have released a larger number of adverts, many of which have relatively low sums of money spent on them.

Labour, by contrast, have focused more heavily on messages to activate their supporters—general sentiments or calls to action, rather than fact checkable claims. They have also put out fewer adverts overall, but have spent more heavily on some individual adverts than the Conservatives.

The content of the ads has, understandably, attracted a lot of attention. An article by First Draft, which analysed ads put out by the main parties over a limited four day period in early December, found that a majority of the Conservative ads during this period included or linked to claims that Full Fact has questioned, while Labour’s ads during this four day period did not. And it’s certainly true that many Conservative ads have included claims we’ve said are misleading.

But we’ve seen claims on social media misinterpreting First Draft’s article to suggest that Full Fact has found that “0%” of Labour ads in this election were misleading. That’s not true: Full Fact wouldn’t make such a statement, and Labour definitely has released ads that contain claims we’ve disputed. (There are also plenty of ads from Labour that contain statements we wouldn’t consider fact checkable, but which we’re pretty sure the other parties would dispute, such as “Only Labour will save our NHS”.)

The reason Full Fact wouldn’t make this kind of statement is that, simply, we can’t say objectively how many false claims are contained in the thousands upon thousands of ads that have run over the course of the campaign. Despite our best efforts, we can’t fact check every single ad. But we can talk about the claims we did fact check which appeared in ads from the parties.

Here, we look at how the two biggest parties have used Facebook ads in the election so far—and how well they match up to the facts.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Conservatives

Before the election

For the Conservatives on Facebook, the election didn’t start on 31 October when the election bill received Royal Assent, but on 23 July when Boris Johnson was announced as the new leader of the Conservative Party, and thus Prime Minister.

By the end of the day over 150 ads had been posted from Conservative accounts. The pre-election period saw the Conservatives trial some of their most familiar messaging, including over 2,000 ads in the week of 29 July primarily telling users about Mr Johnson’s pledge to recruit 20,000 more police officers.

That’s a pledge that needs some context. 20,000 police officers over the next three years would not entirely restore the number lost since 2010. After considering the growth in the population, the number of police officers per person in England will be 8% lower than in 2010.

From mid-August the number of new ads slowed down considerably. However, we can’t be sure this meant people saw fewer ads. Most of the big ads posted in that early flurry are still active now, and we can’t say when people viewed them over the past four months.

That aside, the pre-election period saw more ads focusing on Mr Johnson’s pledges including the claim to deliver 40 new hospitals (it’s six in the next parliament, and none is a completely new hospital), £34 billion a year for the NHS (it’s £20.5 billion a year after inflation) and that this would represent the biggest funding boost ever for the NHS (it wouldn’t).

And September also saw the Conservatives post ads about their education spending pledge accompanied by a BBC article with a headline edited by the Conservatives to make it seem like the BBC endorsed the figure (when it actually criticised the calculations).

After we pointed this out to Facebook it deactivated the misleading ads and said it was working to ensure advertisers couldn’t edit third party content in future.

The campaign

The Conservatives started the campaign itself with messaging that didn’t include many factual claims, focusing on introducing local candidates and targeting marginal seats. The next week, commencing 4 November, saw relatively few ads, around 80, but with a big reach. Ads released this week had over seven million impressions as of 11 December.

As well as continuing the simple “Vote Conservative” messaging, new ads also included accusations that Labour would take SNP support in a future coalition in exchange for a second Scottish independence referendum, as well as running another Brexit referendum.

The Conservatives also attacked Labour’s Brexit policy, and highlighted endorsements from former Labour MPs including Ian Austin.

The third week of the campaign saw the Conservatives ratchet up their attacks on the “Cost of Corbyn”, after it published analysis reported by the Sunday papers costing Labour’s policy plans.

We wrote about how these costs had serious problems. The Labour manifesto had not been published at that point and the Conservatives included costings for things that weren’t Labour policy.

Even if the cost they estimated had been accurate, expressing the cost as a flat £2,400 extra for each household was misleading, as it ignored the fact that Labour never planned to fund spending by spreading out tax rises evenly among households. (Labour eventually announced plans to increase taxes on primarily higher earners and businesses.)

Misrepresentation of Labour’s policy programme was a continuing trope of the Conservative ad campaign.

Looking at the Conservative ads you would also think Labour plans a reduction of the inheritance tax threshold to £125,000 and a “garden tax” (neither of which are in its manifesto).

Both are things Labour has previously discussed, but the way in which they were presented in Conservative ads made them sound like firm policy proposals.

Not all attack ads have been misleading however. The Conservatives also ran ads pointing out Labour’s plan to scrap the marriage allowance, which undermines Labour’s claim that its tax increases will only fall on the top 5% of taxpayers because the marriage allowance also benefits people who earn less.

Into the back-half of the campaign, the Conservatives released ads repeating their pledges on health, focusing on the misleading claim about the “record” NHS funding boost and the pledge to recruit 50,000 “more nurses”, a figure which includes retaining around 18,500 who already work in the NHS.

Facebook also banned a Conservative ad which used footage of BBC presenters because it infringed the BBC’s intellectual property rights. The BBC claimed the ad portrayed its reporters in a way that suggested they supported the party.

The escalation in the number of ads and ad spend continued into the final full week of the campaign, the biggest of which was another dubious Conservative line claiming that “we’re having this election because Parliament are blocking Brexit.”

Parliament voted for the new Brexit deal before being dissolved, but voted against the programme motion which gave just two days for scrutiny.

All in all, amidst claim-light ads pledging to “Get Brexit Done” and asking Facebook users to stop the “gridlock” in Parliament, the Conservative ad operation has been typified by exaggeration of its own policy platform, and misrepresentation of the opposition’s.

Labour

Compared to the Conservatives and their new leader, Labour did not put out a large number of adverts over the summer months or in the run up to the election campaign.

The first week of the campaign, starting the week of 28 October saw lots of relatively simple, claim-free ads telling people an election had been called and that Labour is “ready to rebuild and transform our country.”

There were other ads attacking the Conservatives over fracking and being supported by billionaires, but the most questionable claim in the ads was that a US trade deal would see “skyrocketing costs for life-saving medicines.”

We looked into this when Labour had put a firm price on the claim—an increase of £500 million a week for the NHS—and found that while it is possible that a trade deal could see drug prices rise, that figure was an unrealistic, rough calculation that represented an extreme and unprecedented scenario.

The second week saw a slew of similar ads all suggesting that Labour and not the Liberal Democrats were the only party who could stop “Boris Johnson’s disastrous Brexit”. As we noted above, that’s a statement the Liberal Democrats would probably disagree with, but not fact checkable.

The third week saw Labour dramatically increase the amount of money it spent on Facebook ads. The majority of this went into ads which pushed Labour’s plan to hold a second referendum on Brexit.

Most of the rest attacked the Conservatives over the NHS and a potential US trade deal, including the first direct mention of the £500 million a week figure for medicines.

Labour also spent heavily in the fourth week, following the launch of its manifesto on the Thursday.

Over £20,000 was spent on a single ad showing Jeremy Corbyn summing up the manifesto in 60 seconds. Over £10,000 was spent on an ad pledging to recompense the WASPI women, which we’ve written about here.

Lots was also spent promoting a video of a doctor critiquing claims the Conservatives made about promising to deliver 40 new hospitals, £34 billion a year for the NHS, and also that a previous promise to increase GP numbers was not delivered. (Labour’s video was broadly accurate in its assessment of those claims.)

The party also promoted papers it was leaked detailing discussions between UK and US trade representatives. We’ve written about these documents here, making it clear that they don’t tell us much about how the UK responded to the USA’s negotiating objectives.

The biggest message during the fifth week was not about policies or attacking the Conservatives, but simply reminding people to register to vote before the deadline on 26 November.

Labour also ran a number of ads claiming that 95% of people would not be affected by its changes to tax rates. As we noted above, we wrote about how this claim ignores indirect taxes and the removal of the marriage allowance tax relief. However, these ads received relatively little funding and were probably not widely seen.

In the final full week of the campaign, Labour continued to push ads warning of the consequences of a US trade deal on the NHS and possible privatisation under the Conservatives (an issue that we wrote about here). It also highlighted its new policy to cut commuter rail fares by a third, and ran messages to inform people where their polling station is.

But the biggest spend went into ads on the WASPI women policy, and a video message from a person with cancer urging voters to vote Labour over the Conservatives due to concerns about the future of the NHS.

In the week of the vote, we know Labour promoted ads highlighting the story of a boy with pneumonia in Leeds General Infirmary who had to be treated on the floor due to a lack of beds.

We can also see that Labour did start to run a number of ads which pushed factually inaccurate claims. These included ads on how much Labour’s policies would save the average family—a highly misleading claim that we described in our fact check as “not credible”— and how much the budget for social care has reduced since 2010.

However due to serious problems with Facebook’s ad library in the final days of the campaign, we can’t see the scale of these ads, though they appear to have been overshadowed by the less claim-heavy adverts.

In summary, while Labour’s online ad campaign has featured multiple instances of misleading or exaggerated claims, in general it has been typified by more general attacks on rival parties, articulating its own pledges, and efforts to ensure its supporters vote.