How to spot misleading images online

Edited or misleading images are some of the most common kinds of misinformation found online, but they can sometimes be hard to spot. Below are examples of image-based misinformation we’ve encountered in our work, and advice on how to verify things you may encounter every day.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Out of context images

You’ve probably encountered an image taken out of context online, whether you know it or not. Pictures of crowds, litter, and misbehaving mothers have all been sources of out of context misinformation.

This image claiming to show a rally in support of far-right activist Tommy Robinson and US President Donald Trump in London was shared thousands of times.

How did we find the correct image? If you are suspicious of an image online, but still not certain that the image is misleading, one of the best options is to do a reverse image search. The popular method to do this is via Google image search. If using Google Chrome, you can right-click on the image and click “Search image with Google”. Google Lens will then appear at the side of the screen giving you the option to “find image source”. Clicking this will open a new tab that should show you websites that include matching images and visually similar images. You can also see visual matches if you scroll down on Google Lens.

You can also reverse search using an image’s URL. Right-click on the image you want to search for and copy the image address/URL. Then go to http://images.google.com and click the camera icon in the search bar. Paste the image address into the search box under where it says “Paste image link” and then click “Search”.

You can also do reverse image searches from the Google Chrome app on your mobile phone. Hold your finger on the image for a couple of seconds and then select the “Search image with Google” option.

If searching with Google doesn’t find any results, there are many alternatives: you can use Bing, the dedicated reverse image search engine TinEye, or install a Google Chrome plug-in called RevEye, which allows you to reverse image search on five search engines in one go.

Sometimes, finding the context for these images can also be as simple as searching a description of what’s in the picture. If you were checking whether this photo is of women from the Red Cross landing on a Normandy beach, googling “Red Cross women Normandy Landing” brings up the true story behind the photo.

Edited images

Images and videos that have been edited are the bread and butter of the internet. However, this means that when they’re used for nefarious or misleading purposes, they can be easy to discount or miss.

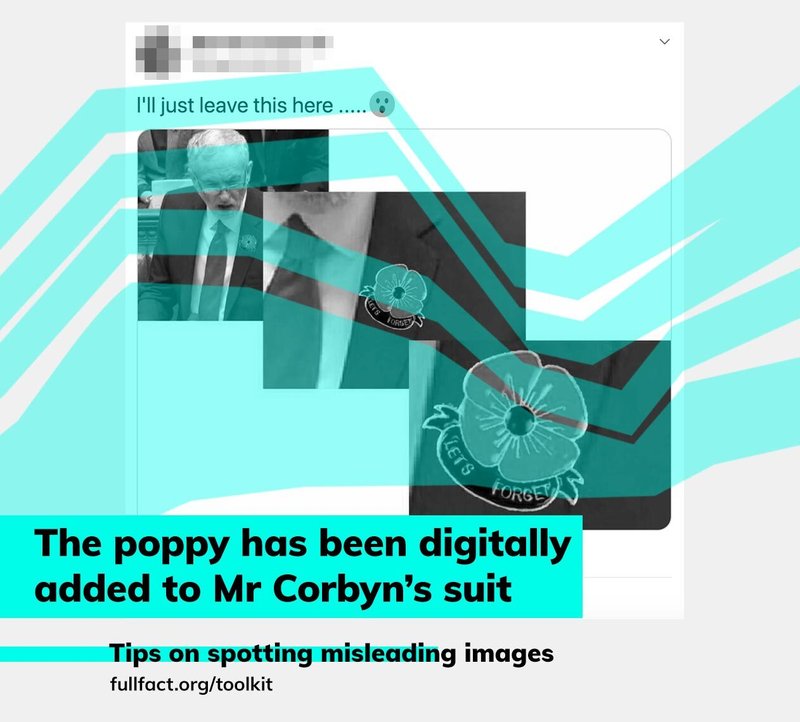

One example of an edited image is one that claimed to show former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn wearing a poppy pin that said “lets forget.”

Actually, the poppy had been edited onto Mr Corbyn’s suit.

If you look behind Mr Corbyn, you can also see a woman wearing what appears to be a yellow daffodil, a pin by Marie Curie that is typically worn in March, not November, when Remembrance Sunday is held.

Misidentification

An often forgotten misinformation trend online is misidentified people. This often happens to public figures, but can happen to the general public too.

One repeated claim is that Nigel Farage was photographed with former National Front member Martin Webster.

While reverse image searching can help in this situation, verifying this photo involved speaking to those with knowledge of the situation at the time it was taken. Similarly, when a young person was misidentified during a Black Lives Matter protest, friends online verified that the young man had been wrongly accused. So at times, image verification is as much about asking the people involved as it is using fancy search tools.

So apart from these tools and tricks, how should you approach verifying images you see online?

Think before you share

If you see an image online, especially one going viral, ask yourself if it makes sense.

Firstly, does the context make sense, and does it fit with what you already know to be correct?

If you are suspicious of the image, some other simple questions can help interrogate further. Do the details in the picture fit with the description? For example, are there any landmarks you could identify or recognise? Many cities have iconic skylines and key buildings. You could also check if the weather in the picture matches up with other pictures or the forecast for that day.

You can also look at what’s going on in the image—for example, are the people in it praying rather than protesting?

If the image has been shared on social media, it’s also worth looking at the comments under a post. If there is something wrong with the image, it’s possible that lots of other people have also expressed doubt, or even debunked it outright.

Familiarise yourself with the internet and its memes/jokes

Knowing what communicating online is like, including knowledge of commonly cited memes and jokes can help you avoid falling into some common misinformation traps.

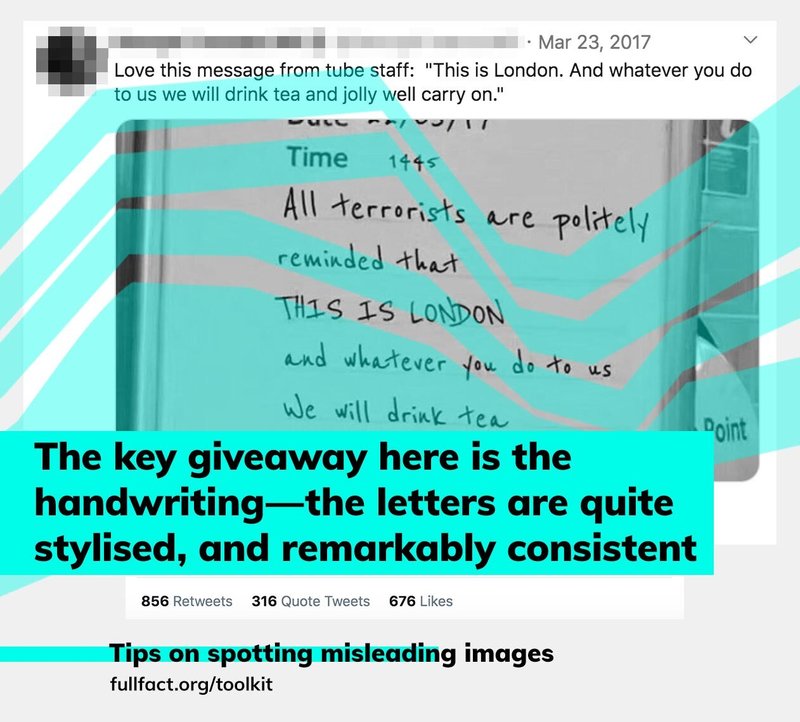

Messages on the London Underground are classics of the doctored image genre. After the Westminster terror attack, one MP shared an image of this message apparently written on a London Underground service information board. It was quoted by another MP in the House of Commons.

Big news stories also naturally attract memes and misinformation. The World Cup also saw an avalanche of memes around the theme of “football’s coming home”. So the image claiming to show that a government minister’s resignation letter spelt out “it’s coming home” should arouse immediate suspicion. It’s not genuine—but how can you confirm this?

To be absolutely certain it’s not all it appears to be, you can try and find the original image yourself. If it's a significant document, it’s highly likely that major news outlets will also be reporting on it. Googling “David Davis resignation letter” brings up a number of news outlets that reported the wording of his letter in full, alongside a photo of the original letter. Neither the text nor the letter’s layout matches up with the “it’s coming home” version, confirming that it is not genuine.

If an image contains a lot of text, you can also base your digging around that.

For example, if an image looks like it’s from a BBC article or website, it should show up if you put the exact wording into google. Putting the text in “quotation marks” will only bring up pages where the wording matches exactly.

And if you’re ever in doubt, it’s always worth heading over to our website to see if we’ve already answered your question about an image, or sending it to us via our contact form.

Update 6 April 2023

We updated this guide in April 2023 to reflect changes to the reverse Google image search function.