BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We’ve always had immigration … up until 2004, we had levels of around 50,000 a year and it worked very well ... We then had uncontrolled, chaotic immigration since then.”

Richard Tice, 1 December 2016

It’s incorrect to say immigration or net migration was around 50,000 a year before 2004. Immigration did increase notably after 2004, but these figures don’t reflect the scale.

Mr Tice might have been referring just to immigration from the rest of the EU, in the context of the debate. Or he might have been talking about overall net migration, including people who are emigrating, in the late 1990s. These levels are closer to the mark. We’ve asked his campaign for a source.

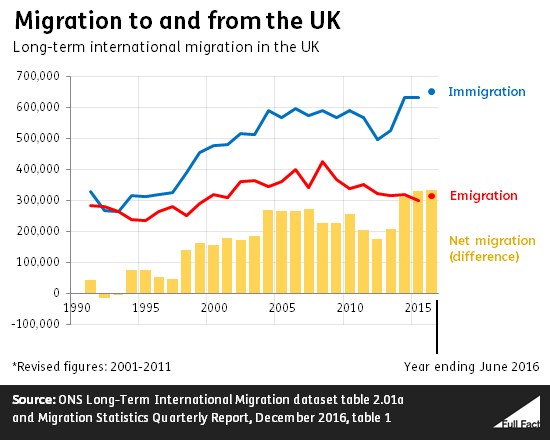

Whatever particular figures he meant to refer to, the point stands that net migration is, historically, at very high levels.

It’s hard to look at what was happening in the mid-2000s anyway because the figures from the time are known to be wrong, and will underestimate the scale of immigration. The ONS has produced new estimates for overall net migration, but not for immigration or emigration alone.

Here’s what the best available figures tell us.

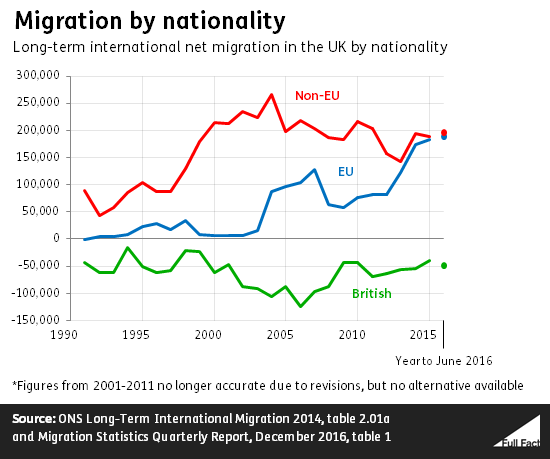

At the turn of the century, estimates show 'net EU immigration' to the UK was about 7,000 a year. That means every year, about 7,000 more people were coming to live here from other EU countries than were moving out to live elsewhere in the EU.

After 2004, when ten new countries joined the EU, that was up to more than 100,000.

Overall net migration to the UK—including people moving from and to non-EU countries—was running at about 50,000 a year in the late 1990s, and about 180,000 people a year at the start of the 2000s. It’s estimated at 330,000 now.

We haven’t been able to control the scale of EU migration to or from the UK. But we’ll leave “chaotic” to the reader’s judgement.

Update (4 January 2016)

We've added information about trends in EU immigration to clarify what the figures show.

“Once we trigger Article 50, it runs for two years. We have no control over extending it. The other 27 member states decide whether there’s an extension or not.”

Alan Johnson MP, 1 December 2016

This is correct.

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union sets the procedure for leaving. It says:

“The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after… notification… unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.”

In other words, if the UK triggers Article 50 and nothing else happens, we will be out of the EU after two years.

If there's a withdrawal agreement with the remaining 27 members—setting the terms of divorce, effectively—that can set an earlier or later date for the UK’s departure. And if all countries agree, the two-year period for negotiating that agreement can be extended.

Find out more in our guide to leaving the EU.

“I personally would like to see us come out without even bothering to trigger Article 50.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 1 December 2016

It is possible to leave the EU without triggering Article 50. It would be a little like quitting your job by simply walking out of the office, rather than giving notice and serving it out.

“Article 50 provide[s] the only means of withdrawing from the EU consistent with the UK’s obligations under international law”, according to a House of Lords committee that heard evidence from two leading EU legal experts.

The UK could simply repeal the European Communities Act 1972 and stop turning up to EU meetings. Our courts would no longer recognise EU law, and the remaining EU members would get the message. The problem is that the UK would still be signed up to the EU treaties and would be in breach of those treaties if it went down this road.

As the government appears keen to sign a new treaty with the EU after we leave, and to conclude trade agreements with other countries, it’s unlikely that it will want to go into such negotiations with a reputation for breaking international agreements.

“We talk about honesty in the campaigns, both sides were equally guilty. I am still waiting for my house price to fall by 10%... It was supposed to happen the day after we leave the EU, we were promised a punishment budget.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 1 December 2016

It’s true that campaigners on both sides made false claims before the EU referendum. Sometimes they made false claims about the false claims made by each other.

That said, the Treasury didn’t predict that house prices would fall by 10%, immediately after the UK voted to leave the EU.

The Treasury did say something that sounded similar. It expected house prices to be 10-18% lower than it would have otherwise expected at the end of 2017/18.

That wasn’t a 10-18% fall from what they were on June 23rd 2016, it was a 10-18% fall compared to what they would have been, in the parrallel universe where the UK voted to remain in the EU.

To be fair to the audience member, many news outlets didn’t spell out the difference clearly. Nor did Mr Osborne, then Chancellor of the Exchequer.

It’s also important to spell out the difference between the debate about the short term economic consequences of voting to leave the EU, which created lots of uncertainties, and the long term economic effects of actually leaving the EU and trading under different rules.

Just because the Treasury’s expectations about the immediate impact of a vote to leave were wrong, doesn’t necessarily mean that its long term expectations about different trading arrangements are automatically wrong.

But economic forecasts should always be taken with a pinch of salt.

And there’ll always be a debate about just how ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ the pre-referendum forecasts turn out to be. We’ll never know exactly what would have happened if the referendum result had gone the other way.

The Treasury based its expectations on some key things that didn’t happen. Among other things, it appeared to assume the government would trigger Article 50 straight away, as David Cameron had indicated, and that the Bank of England would keep interest rates the same, which it didn’t.

It’s a similar story with the ‘Brexit budget’ presented by George Osborne, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Alistair Darling, a former Chancellor, which the audience member on BBC Question Time referred to as the ‘punishment budget’.

That was a 7-page pamphlet which republished some of the economic forecasts and gave rough, hypothetical figures for the kinds of cuts which a future government could make—assuming it still wanted to run a balanced budget in 2020/21.

People will disagree on whether that was a believable assumption at the time. The government hasn’t stuck to its aim for a balanced budget, and now plans to run a deficit in 2020/21.

“[HS2] is only going to save a few minutes off the journeys.”

Tim Stanley, 1 December 2016

“Guess what, it won't stop here, you can't get on the train here, we have to go to Leeds so it will take longer to get to London from Wakefield than it does today.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 1 December 2016

The government has produced an analysis of the estimated time it will take to get from “major economic centres” to either London Euston station or Birmingham Curzon Street when the planned HS2 rail network is built. The analysis says these estimates are based on the “fastest typical times” now and the fastest possible journey on HS2.

According to these figures, journey times to London Euston will reduce by up to 81 minutes (from Manchester Airport) or by just 13 minutes (from Derby).

To Birmingham Curzon Street the greatest reduction in journey time will be from Leeds, down 69 minutes, and the smallest reduction in time will be from Sheffield Midland, down just 15 minutes from current journey times.

There will be the same reduction in time between Leeds and Sheffield Midland (15 minutes) while journey times between Leeds and Birmingham Interchange will drop by 102 minutes.

Of course these are just estimates of the fastest possible times. Actual journeys might take longer. And not all of the cities included in the analysis will be directly on the HS2 line. The timings take into account the overall impact of HS2 on the rail network.

But what about journeys from Wakefield to London?

Currently it takes around two hours to get a train directly from Wakefield to Kings Cross station in London.

Assuming that a journey to London using HS2 also goes from Wakefield via Leeds the journey could be a bit faster, but that’s comparing current train times to the fastest possible times projected by the government.

According the government's most recent figures, when the second phase of HS2 is completed in 2033 the journey time from Leeds to London Euston station will have decreased from 131 minutes to 81 minutes, including a five-minute interchange at a new East Midlands hub.

Travelling from Wakefield to Leeds by train currently takes as little as 13 minutes (though it can take over 35 minutes), according to National Rail. This would suggest that a train journey from Wakefield to London using HS2 would take at least 94 minutes, although this doesn’t account for time taken to change trains in Leeds or changes in existing train times by 2033.