BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The Dubs Amendment: 3,000 refugee children?

The government has been accused of accepting thousands fewer child refugees from elsewhere in Europe than it had indicated. The Home Office announced on 8 February that 350 is the limit under the so-called ‘Dubs Amendment’ scheme.

“Just to clarify, there was never a number made. What the government committed to was to make sure every child that came, who might have been through the most horrific situation, would be given as much support as they could possibly have through the local councils, and the local councils have come back and said ‘this is the number we feel we can support.’”

Claire Perry MP, 9 February 2017

“But the original Immigration Act of 2016 did state that we would take 3,000 child refugees? It was in the amendment, it wasn’t accepted?”

David Dimbleby, 9 February 2017

So what happened?

Well, so far as we’re aware, the government never officially said that the number of children resettled under the Dubs Amendment would be 3,000, although there may have been unofficial indications to that effect.

3,000 was the number that campaigners and opposition MPs were pushing for in the spring of 2016. Alfred Dubs, a member of the House of Lords, proposed this number on 21 March in a suggested amendment to the Immigration Bill.

In the lead-up to the vote on the amendment, David Cameron’s government did say that it would resettle 3,000 children and their families—but from the Middle East and North Africa rather than from Europe.

That was on 21 April. On 24 April, MPs rejected the 3,000 target for children already in Europe. The Lords then suggested the following instead:

“The Secretary of State must, as soon as possible after the passing of this Act, make arrangements to relocate to the United Kingdom and support a specified number of unaccompanied refugee children from other countries in Europe.”

The government accepted that version on 4 May, precisely because it didn’t contain a fixed target. Lord Dubs said that the revised version “drops the specific number, because the Government were resistant to that.”

It’s been widely reported that, in a meeting the same day, immigration minister James Brokenshire gave backbench MPs the impression that the number would be in the thousands. The Archbishop of Canterbury says that he and other supporters of the scheme “believed that the Government was committed to welcoming up to 3,000 children under this scheme”.

But Ms Perry is correct that until this week, there was never a “specified number” of refugee children officially announced.

The Dubs Amendment also says that “the number of children to be resettled… shall be determined by the Government in consultation with local authorities”. Councils said that they can handle 400 unaccompanied children, and 50 of those places would be needed for children arriving from Calais under a separate scheme, according to the Home Office’s statement.

“Two and a half million more people went to A&E this year, the NHS has never been busier”

Claire Perry MP, 9 February 2017

Ms Perry is correct that the NHS in England has never been busier, but her phrasing on the figures is a little confusing.

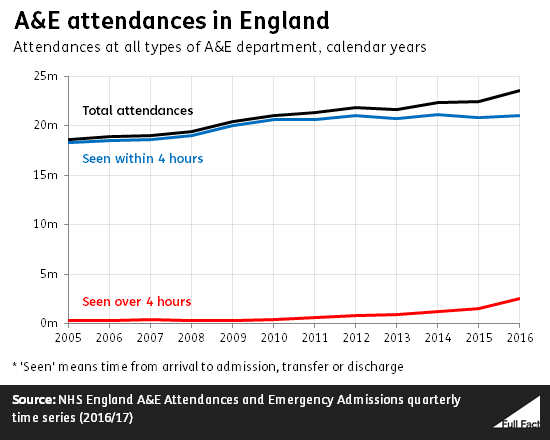

You might think she’s saying 2.5 million more people went to A&E this year compared to last year. Actually this is only correct compared to six years ago, a comparison the Prime Minister stated correctly last month. There were about 1.1 million more attendances at A&E in 2016 compared to 2015.

23.6 million people visited A&E last year. These aren’t all unique individuals: some people visit multiple times and get counted whenever they visit. That’s why we usually call them ‘attendances’. It’s up from 22.4 million in 2015.

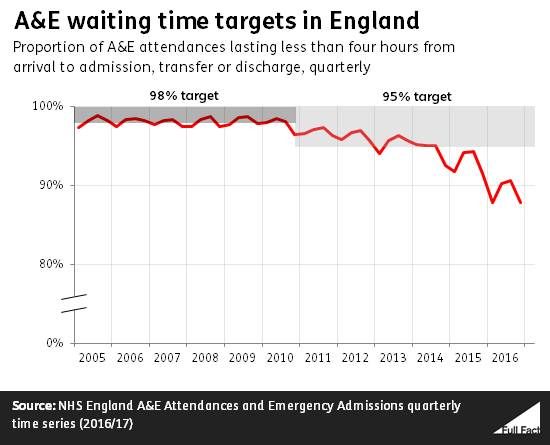

This comes off the back of figures leaked this week suggesting that record numbers of patients spent more than four hours in A&E units in England last month. It’s claimed that 82% were admitted, transferred or discharged from A&E within four hours. The target is 95%.

The longer-term trend shows performance against the 95% target has been deteriorating for several years.

“I’d just like to direct this to the Deputy Leader of UKIP. Your leader, Paul Nuttall, said that he’d like to privatise the NHS.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 9 February 2017

“No he didn’t.”

Peter Whittle AM, UKIP Deputy Leader, 9 February 2017

“He actually praised the Tories for bringing ‘a whiff of privatisation’ into the NHS.”

Owen Smith MP, 9 February 2017

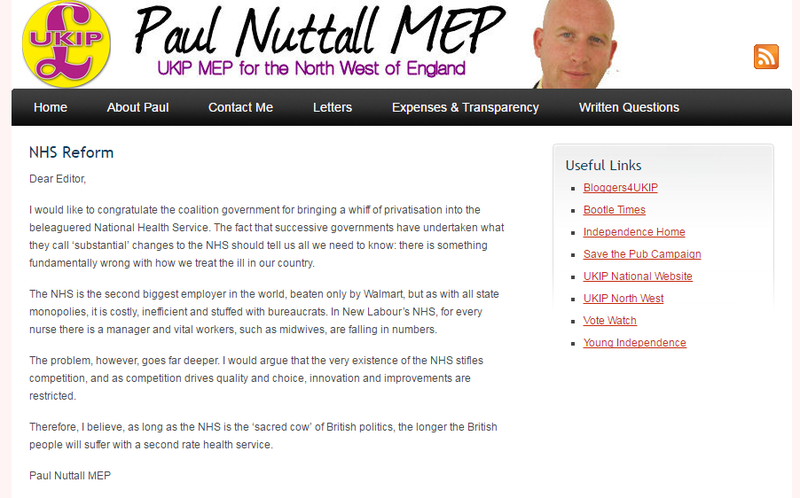

UKIP’s newest leader, Paul Nuttall, had this to say about the NHS a few years ago:

He also said in 2011 that "I believe that the NHS is a monolithic hangover from days gone by... quite frankly I would like to see more free market introduced into the health service”.

When this clip was played to him on Sky News recently, Mr Nuttall responded as follows:

“What I have said about the NHS is simply this: I believe it needs to be streamlined. It cannot be right that 51% of people who work in the NHS in England are not clinically qualified, it’s too big, it’s cumbersome. What I do believe we could have more free market in is in places like procurement whereby the NHS itself is paying sometimes ten to thirty times over the odds for drugs. If you brought in a private company you could hire and fire them on results that they got for the British public.”

His deputy, Mr Whittle, pointed out that NHS privatisation has never been official party policy. The party’s 2015 election manifesto called the NHS a “cherished institution”, and addressed “growing concern” that a EU-US trade deal being negotiated would mean “privatising significant parts of our NHS”.

The party’s health policy for that election began with “keep the NHS free at the point of delivery”.

It’s possible to still have that and have private sector involvement in the NHS. It just depends what we mean by “NHS privatisation”. Private firms can already bid to do work on behalf of the NHS. In that sense, a portion of the service is already “privatised”.

"Privatisation" could also mean moving away from the existing system to a health insurance model, as former UKIP leader Nigel Farage once advocated.

“...if we don't get a good deal, simply falling out of the European Union on World Trade Organisation terms... would cost this country £45 billion in lost GDP.”

Owen Smith MP, 9 February 2017

It isn’t possible to judge this claim based on what Mr Smith said on the programme, since it wasn’t clear which estimate he was referring to, or what time period.

Mr Smith has since told us that he was quoting estimates published by the Treasury before the referendum.

He was quoting them incorrectly. £45 billion was the Treasury’s estimate for the cost to tax revenues after 15 years, rather than the cost to GDP. Since lower tax revenues are a knock-on effect of lower growth, that implies the cost to GDP after 15 years would actually be higher than £45 billion.

The Treasury’s forecast was among the more pessimistic of those published before the referendum, although nearly all agreed that trading only under terms set by the World Trade Organisation was a ‘worst case scenario’ economically.

A suggested cost of £45 billion would be big. For example, it’s nearly twice what local councils put into social care funding last year.

WTO terms of trade

Mr Smith was talking about a future in which the UK doesn’t agree a trade deal, and trade with the EU is carried out under terms set by the World Trade Organisation.

That would mean UK and EU businesses paying tariffs (taxes) on imports and exports in line with other countries who don’t have a trade deal with the EU. They might also face other types of non-tariff barriers to trade, like different kinds of product and service regulations.

Most economic forecasts, although not absolutely every one, suggest this would make life more difficult for UK businesses. They suggest the economy would grow more slowly and the government would collect less tax revenue than under any other set of trade arrangements.

So it isn’t unorthodox to say it would be a bad thing, even if precise forecasts will never be certain.