BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“When we negotiated the outcome of the justice and home affairs… brief in Europe, [Theresa May] negotiated us out of 100 out of 135 aspects of the treaty.”

David Davis, 1 June 2017

The Coalition government did opt out of around 130 previously enacted EU security and criminal justice laws, 35 of which it subsequently opted back into. Theresa May was Home Secretary at the time, but the right to opt out of the measures was negotiated under a previous government.

The Treaty of Lisbon came into force in 2009 and intended to reform the European Union following its enlargement from 15 to 27 member countries. One element of the Treaty was that security and justice measures would no longer require the unanimous agreement of member countries.

But at the time the UK Labour government, along with Ireland, negotiated the ability to opt out of future security and justice laws on a case-by-case basis. In addition, they also negotiated the ability to opt out of all 130 pre-Lisbon security and justice laws, with the provision that they could opt back into some of them.

In July 2013 the Coalition government notified the EU that it would make use of the block opt-out option. It also decided to opt back into 35 measures that it felt remained in the national interest including, for example, the European Arrest Warrant.

EU members had to agree unanimously on the UK’s opting back into the 35 measures. So there were negotiations required, and they were successful from the UK’s point of view.

Theresa May was Home Secretary at the time, but it’s difficult to say what her exact involvement in negotiations was.

“We’ve got about £9 billion invested in the European Investment Bank, we have contributed for decades to this organisation.”

Suzanne Evans, 1 June 2017

This is right. As with all other members of the EU the UK is a shareholder in the European Investment Bank (EIB). It is the bank of the EU and works closely with the other EU governing bodies, investing in projects across Europe and around the world.

Along with Germany, France and Italy, the UK is one of the largest shareholders in the EIB with shares of 16%.

Earlier this year a committee of Lords said that “it is likely that the UK would claim its called up capital in the event that it ceased to be a shareholder of the EIB”, that was around €3.5 billion in 2016. But it said that “a more useful measure” would be be the UK’s share of the bank’s equity, reserves and profits for that year (known as the bank’s ‘own funds’.)

The EIB had around €66 billion of its own funds in 2016. The UK’s 16% share of that would be €11 billion or just under £9 billion.

The EIB’s rules state that its members must also be member states of the EU. For the UK to remain a member of the EIB after Brexit the rules would have to be changed—something that all the remaining members states would have to agree on.

As well as the UK having shares in the EIB, the bank also invests in projects in the UK. This investment totalled more than €29 billion between 2011 and 2015, followed by another €6.9 billion in 2016. Whether or not the EIB would continue to lend money to projects in the UK is likely to be discussed during Brexit negotiations. It would be possible for this to happen, but it would need the unanimous agreement of finance ministers in all the remaining EU countries.

“If you look at the top 10 Commonwealth countries put together—that’s including India, including Pakistan, including Australia, including Canada—the top 10 make up simply 8% of our exports, not the 44% that the European Union has. And if you take all 52 or 54 Commonwealth countries, they make up just 9% of all our exports.”

Barry Gardiner, 1 June 2017

This is correct.

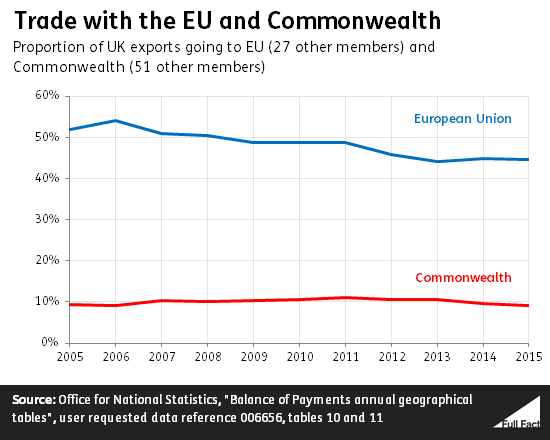

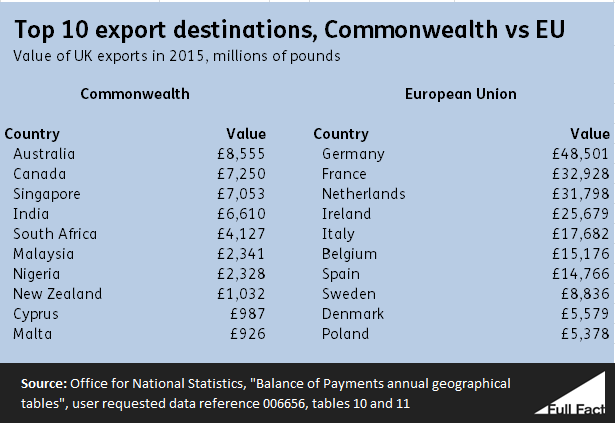

Exports to the 51 other members of the Commonwealth—a club of mostly former British colonies, some of which are very small countries—were just 9% of UK exports in 2015, figures assembled by the House of Commons Library show. The value of those exports has actually fallen in the past few years.

By contrast, 44% of exports go to other EU countries. That share was declining until 2013 but has been steady since.

The Commonwealth isn’t a trading bloc like the EU. While its members trade with one another, there’s no free trade agreement linking them all together.

“Conventional thinking among trade policy experts and policy makers suggests that a free trade area of the Commonwealth would be an utter impossibility for legal and political reasons”, according to a 2013 report for the International Trade Centre. But Brexit provides the opportunity to make trade agreements with individual Commonwealth countries, which we can’t as an EU member.

“Forecasts from [the Treasury] said immediately after the vote to leave in the referendum there would be a minus, there would be a reduction in the size of the British economy in the last quarter and the current quarter. What happened? We were one of the fastest growing nations in the G7 in that time.”

David Davis, 1 June 2017

“David... just this week it’s been revealed that we have plummeted as a country from the fastest-growing economy amongst developed economies to the slowest in a three-month period”

Nick Clegg, 1 June 2017

Mr Davis’s basic point is correct. The Treasury’s forecasts for the impact of a vote to leave didn’t reflect how the economy performed after the vote to leave the EU. He’s not correct on the specific timings, although he may have just mis-spoken.

HM Treasury, the department which oversees government spending, forecast last year that a vote to leave the EU would result in a year-long recession, beginning in the third quarter of 2016.

But in the third quarter of 2016 the UK was the third fastest-growing economy in the in the G7, a group of ‘major advanced economies’. In the fourth quarter it grew the fastest. That ran counter to the expectations of most economic forecasts made before the referendum.

Then, as Mr Clegg points out, in the first three months of this year the UK dropped in the rankings. It joined Italy and the USA as one of the three slowest-growing economies in the same group—not the single slowest as Nick Clegg says. The Office for National Statistics hasn’t published estimates for months after that yet.

So the debate now isn’t about whether the Treasury’s forecasts were a bad guide to what happened immediately after the vote (they were) but whether it was mainly the timing they got wrong.

A survey of professional economists run by the Financial Times in January 2017 found that the majority weren’t reassured by the apparently solid performance of the UK economy since the vote to leave the EU. Some took this view despite conceding that many of the short-term forecasts had been overly pessimistic.

“One of the major areas he [Jeremy Corbyn] is looking at raising tax is corporation tax. Now corporation tax has come down over the years in rate terms, in terms of the actual rate, and as it’s come down what’s happened is the amount collected has gone up. It’s now £56 billion, the highest level ever.”

David Davis, 1 June 2017

“Under Margaret Thatcher corporation tax in this country was 52% and the lowest she ever got it to in the last years of her reign as Prime Minister was 34%. This government in 2010 has taken it from 28% to 19% and says that it will go down to 17%. Our proposal is to take it back up to 26%, half of where it was under Margaret Thatcher and still 2 points lower than it was in 2010 when this government came into office.

Barry Gardiner, 1 June 2017

Labour has committed to raising the main rate of corporation tax to 26% if they win the election. At the moment it is at 19% and it's set to fall to 17% in April 2020.

It’s correct that the rate of corporation tax has fallen since 2010. In 2010 the standard rate of corporation tax was set at 28%. This was reduced by the Coalition and Conservative governments several times, ending up at 19% in April 2017. Its 2017 election manifesto promises to reduce corporation tax to 17% by 2020, in line with recent plans.

Rates are only half the picture when it comes to how much we pay in tax. Cuts to corporation tax rates have been partly offset by measures to lower capital allowances or to reduce tax avoidance.

It’s also correct that corporation tax revenues have increased since 2010, although Mr Davis got the figure wrong. Last year in 2016/17 the UK government raised £50 billion from corporation tax, a cash increase of about £5 billion compared to the same time the year before.

The amount collected by the government hasn’t risen simply because the rate has fallen. Successive policy costings done under the Coalition and Conservative governments suggest it would have collected more in corporation tax if it hadn’t lowered the rates (even though such estimates are quite uncertain). You’d expect the cash value of corporation tax receipts to rise each year as the economy grew, all else being equal.

As Mr Davis said, the cash value now is the highest recorded since 1980.

It’s more useful to look at what has happened to this amount as a percentage of the UK’s overall economic output. Initially, as a share of our GDP, the revenue from all forms of corporation tax (including things like Bank Surcharge, which aren’t included in the £50 billion figure above) increased from 2009/10 to 2011/12. It then fell for two years and levelled out for two more. Last year the share started to increase again.

When Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979 the standard rate of corporation tax was set at 52%. It was reduced over the next few years and the last time it was changed while she was Prime Minister was in 1990 when it was cut to 34%.

The small companies rate of corporation tax also fell while Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister.