BBC Question Time, factchecked

Question Time this week was in Portsmouth. On the panel were Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg, Labour's shadow attorney general Shami Chakrabarti, SNP's former first minister of Scotland Alex Salmond, feminist writer Germaine Greer and political editor of the Sunday Express Camilla Tominey.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“He [Mark Carney] warned that there would be a technical recession, but that is a recession … he said that, he was completely wrong, the Treasury was worse, it said there would be between 500,000 and 800,000 jobs lost purely on a vote to leave, not actually anything happening, just on the vote”

Jacob Rees-Mogg, 26 October 2017

In May 2016, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, said: “we would expect a “material slowing in growth, a notable rise in inflation, a challenging trade-off” in the case of a Brexit vote. He added, “of course there’s a range of possible scenarios around those directions, which could possibly include a technical recession”.

In the same month, the Treasury said: “Britain’s economy would be tipped into a year-long recession, with at least 500,000 jobs lost and GDP around 3.6% lower, following a vote to leave the EU, new Treasury analysis launched today by the Prime Minister and Chancellor shows.”

“Recession” is a general term for a decline in economic growth over a period of at least a few months. A technical recession is two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

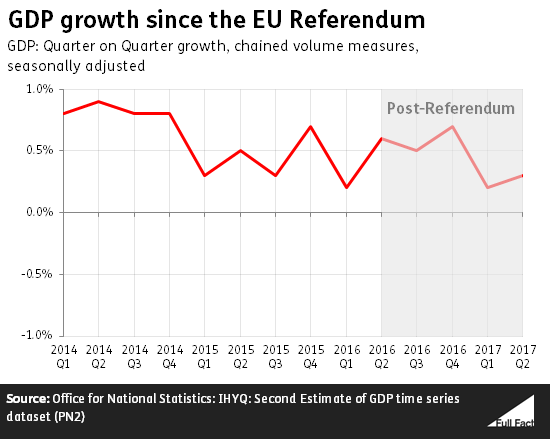

GDP has actually grown in every quarter since the Brexit vote in June 2016. From July to September 2016, it grew by 0.5% compared to the previous quarter. In the full year since June 2016, GDP grew by 1.7%. Other EU economies have grown faster over that period.

GDP has since grown by an estimated 0.4% from July to September this year.

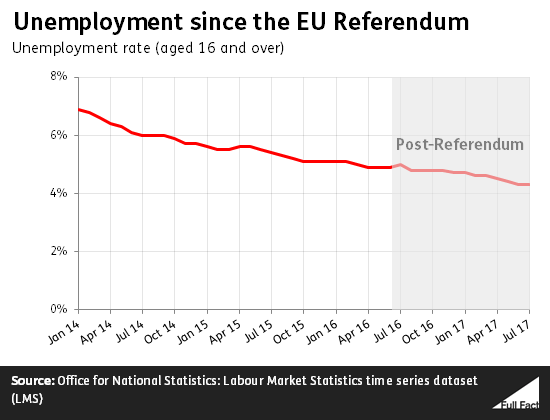

There were also 317,000 more people in employment from June to August this year, compared with the same period in 2016.

Unemployment was at 4.9% in June 2016, rising to 5% in July. It has since steadily fallen to 4.3%, which is the lowest level since 1975.

“When we leave, we can set our own tariffs. Tariffs set at the European level make food, clothing and footwear more expensive. They are the highest proportion of the poorest in society’s expenditure. If we can get rid of those tariffs, we help the worst off in society.”

Jacob Rees-Mogg, 26 October 2017

It’s correct that, after leaving the EU customs union, the UK would be able to choose what tariffs—which are basically taxes on imports or exports—it puts on imports from other countries. The UK wouldn’t have a completely free hand to do this, however.

At the moment, the UK can’t do this because the EU sets a Common External Tariff on anyone it doesn't have a trade deal with.

Higher tariffs mean products can be more expensive after they’ve been imported.

The EU sets relatively high import tariffs on agricultural products compared to everything else. The average EU tariff on agriculture was roughly 11% in 2016, compared to about 4% for other products.

Tariffs on dairy products are as high as 36% on average, those on clothing can average just under 12%, and those on footwear face about 4%.

The lowest-earning households spend a lot of their money on food and clothes

Mr Rees-Mogg also claims food, drink and clothing make up the highest proportion of the poorest households’ spending.

What makes up the biggest chunk depends on how you categorise different kinds of spending, but these items certainly make up a big part of what low earners spend each week. The latest figures for these are for 2015/16, from the Office for National Statistics.

The lowest-earning 10% of households spend about 17% of their weekly income on food and non-alcoholic drinks. Another 4.5% goes on clothes and 4% goes on alcohol. Meanwhile a full 22% goes on housing and fuel.

The highest-earning 10% are very different. They spend 7.5% on food and drink, 4% on clothes and 1.5% on alcohol. Their biggest items are transport (16%) and leisure (13.5%).

So does this mean getting rid of tariffs will help the worst off?

It’s likely that lower tariffs will help with the cost of certain products, but it’s also just one part of a bigger picture. Tariffs aren’t the only thing that will affect household incomes after Brexit.

The value of the pound has fallen since the referendum, and that has increased pressure on food and drink prices for everyone.

Despite previous inaccurate predictions (covered above), economists generally expect there to be a negative impact on the UK’s economic growth in the coming years as a result of leaving the EU. If that happens household incomes will be lower than they otherwise would have been.

“To take them out using special services, I think, would be illegal under UK and international law.”

Jacob Rees-Mogg, 26 October 2017

“You can sometimes use lethal force. ... You can even do it on the street of your town in the UK, if it is strictly necessary to save life. That is lawful under English criminal law and under international law.”

Shami Chakrabarti, 26 October 2017

There’s a debate going on at the moment about what the government can and should do with British citizens in or returning from fighting in Syria for jihadist groups.

There is no single authoritative statement of what’s allowed in international law. It starts with written treaties agreed between countries, but also includes custom and practice. All of these can be interpreted differently by different countries and not all countries are signed up to all treaties.

The UK government has said that killing people in Syria can be lawful under international law. An RAF drone targeted and killed Reyaad Khan, a British national, in Syria in 2015.

The UK government’s view of international law was set out in a speech by the Attorney General earlier this year.

The UN Charter, the founding treaty of the United Nations, requires member states to “refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force”. Article 51 makes an exception for “inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations”. That’s all in black and white.

“Like many other states”, the Attorney General said, the UK believes that right extends to “self-defence against an ‘imminent’ armed attack” not just to when a country has already been attacked.

In warfare, it's generally lawful to target enemy troops. But the UK government takes the view that international law may allow the use of force against individuals who are not members of a conventional foreign army. It says force, which may be lethal force, may be used against these individuals if that's what's needed to defend the UK against an actual or imminent armed attack.

The UK's view is that it can use force in self-defence against individuals based in a foreign state if that state is unable or unwilling to prevent an actual or imminent armed attack on UK interests. The same would apply if the foreign state does not have effective control of the territory from which the attack might come.

The Attorney General says “a number of states” agree with the UK on that.

So those are the arguments you would need to accept to agree with to accept the UK government’s argument about what strikes can be legal in international law.

Finally, you would have to decide whether a particular strike is legal based on the facts of the case. Is it necessary? Is it proportionate? And what counts as an imminent threat?

The Security Service MI5 says that “hundreds of British extremists” have travelled to Syria. Its Director General said in a speech: “A growing proportion of our casework now has some link to Syria, mostly concerning individuals from the UK who have travelled to fight there or who aspire to do so.”

“We got the figures the other day, decreasing numbers of poor and non-white students at Oxford and Cambridge”

David Dimbleby, 26 October 2017

The proportion of students from a BME background getting a place at Oxford and Cambridge has been increasing for the last few years. But the proportion of undergraduates at Cambridge from disadvantaged areas has fallen in recent years, while the proportion at Oxford has increased slightly.

The measure of disadvantage here is called the ‘POLAR3’ method, which measures a young person’s likelihood of progressing into higher education based upon where they live.

The proportion of Oxford’s placed applicants from ethnic minority backgrounds increased from 12% in 2010 to 16% in 2016, while at Cambridge the proportion increased from 16% to 21%, according to data from UCAS. For black students specifically, the proportions are much lower - 1.3% up from 0.7% at Oxford and 1.5% up from 0.5% at Cambridge.

HESA data on the percentage of students from low participation neighbourhoods, shows a small decrease for Cambridge from 3.6% in 2013-14 to 3.1% in 2015/16, while Oxford increased from 2.1% to 3.3%.