BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Islington in North London this week. The panelists were: Housing Minister Dominic Raab, Shadow Secretary of State for Women and Equalities Dawn Butler, businesswoman and campaigner Gina Miller, comedian Nish Kumar and journalist Piers Morgan.

We factchecked claims on NHS spending, the impact of an increasing population on the NHS, ambulance delays and whether the NHS had more doctors, beds and flu vaccines available. We published three of these factchecks on 12 January. The factcheck titled "NHS: More beds, more doctors, and more flu vaccines?" was published on 16 January as Mr Raab told us he would be able to provide more information about his claim after the weekend.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We’ve got more beds, more doctors, more flu vaccines available than ever before.”

Dominic Raab MP, 11 January 2018

The number of hospital beds available overall in NHS England has been decreasing over time. Mr Raab told us he was specifically referring to the number of beds used by patients who have delayed transfers of care—they are medically fit to leave hospital but haven’t yet been discharged. 1,300 fewer beds were occupied by patients with delayed transfers of care in November 2017 than in the same month the year before.

The number of doctors working in hospitals and community health services across NHS England has increased since 2010 and NHS England reported at the start of winter 2017 that more flu vaccines were being made available than ever before. Public Health England doesn’t yet have complete data on how many people have received the flu vaccine this winter.

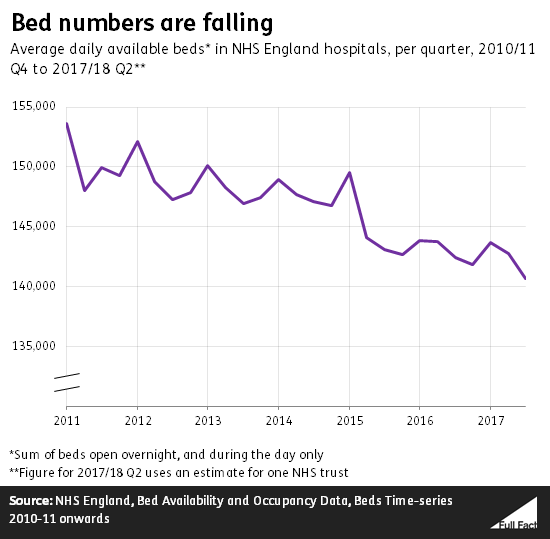

The number of beds has been consistently falling over time

The number of NHS hospital beds in England has more than halved in the past thirty years, according to analysis by the health think tank the King’s Fund.

On average, there were estimated to be 141,000 beds available each day between July and September 2017, including both beds open overnight, and during the day only.

This is a fall of about 1,800 beds, compared to the same period in 2016. Compared to 2015, it’s a fall of about 2,400.

The average percentage of these beds which were occupied each day between July and September 2017 was 87.1%. That is 0.3 percentage points lower than at the same time the previous year, so there were slightly more beds free. But generally the proportion of hospital beds occupied has been increasing since at least 2010.

The King’s Fund points out that “Most other advanced health care systems have also reduced bed numbers in recent years” due to medical innovations which decrease the amount of time patients spend in hospital. For example certain operations can now be carried out in such a way that patients can leave on the same day. There’s also been a move away from hospitalising patients with mental health problems and learning disabilities, instead providing care in the community.

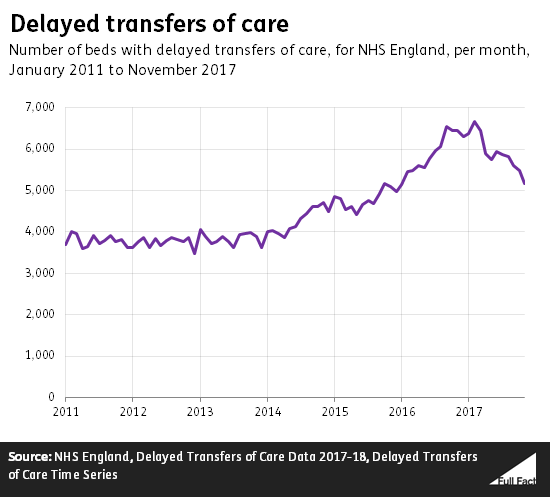

Fewer beds are being used by delayed transfers of care

Mr Raab directed us to NHS England figures showing a decrease in delayed transfers of care. This refers to the number of beds occupied by patients who are medically fit to leave hospital, but haven’t yet been discharged.

The number of these delays fell by about 20% between November 2016 and 2017. That meant around 1,300 fewer beds were used by patients with delayed transfers of care.

The number of beds used up as a result of delayed transfers is the lowest it has been since the winter of 2015/16, but it remains higher than at most points since at least August 2010.

The number of doctors is going up

There were 109,000 full-time equivalent doctors working in NHS hospitals and community health services in England in September 2017. That’s an increase of around 2,800 since September 2016, and around 11,900 since the same month in 2010—the first year of the Coalition government.

The number of doctors has been rising steadily over time, but without taking into account other factors like patient numbers pressures on services this increase doesn’t tell us much about the impact on patients or the NHS.

This doesn’t include the number of GPs and we don’t have comparable figures going as far back as 2010 for them, but you can read more about GP numbers here.

Flu vaccines

Mr Raab directed us to a statement on flu vaccines made by NHS England in October. In it, Professor Dame Sally Davies, Chief Medical Officer for England said that there were “more people eligible than ever before”, with “the vaccine available in more locations”. The NHS England statement also announced “significant expansion of the national flu vaccination programme for key groups, aiming to offer the vaccine to over 21 million people.”

Since 2012 a programme of vaccinating healthy children aged two to 17 has begun to be rolled out. Children aged two to seven were eligible to receive the vaccine last year and this year eligibility for vaccination was extended to include eight year olds.

Public Health England (PHE) publishes data on the uptake of the seasonal flu vaccine among GP patients in England, focusing on vulnerable groups who are offered the vaccine free of charge. The proportion of patients aged over 65, pregnant women and small children who received the flu vaccine was higher in September to November 2017 than it had been the year before.

PHE say they’re still collecting data on how many people in total have received the flu vaccine this winter, so we can’t yet fully compare uptake to previous years. In 2016/17 the number of people in each of the groups given the vaccine free of charge had increased compared to the year before, although for over 65s the proportion getting the vaccine decreased slightly.

“And the point I was going to make was that the population has grown by a third since the start of the NHS, and is projected to grow to 74 million, another 10 million by 2039. This population is also living a lot longer, so we have a massively larger number of people living a lot longer, putting a huge new strain on a system that simply wasn't devised to tolerate this number of people using it.”

Piers Morgan, 11 January 2018

The number of people in the UK is growing, and is projected to keep growing. Life expectancy is also up. More people and increased costs are adding to pressures on the NHS.

The UK population has increased by about 31% since 1951, the census taken a few years after the NHS was founded. That’s about a third, as Mr Morgan said. The population hit an estimated 65.6 million in 2016, and is projected to continue rising to 72.5 million by 2039. It’s only currently projected to reach 74 million in 2047.

People are also living longer. The average life expectancy for men born between 2014 and 2016 is 79 (up from 71 in 1980 to 1982), and for women it’s 83 (up from 77 in 1980/2). 65 year-old men could expect to live another 19 years in 2014/16 (up from 13 years in 1980/2), while women of that age could expect to live another 21 years (up from 17 years in 1980/2).

Healthy life expectancy, the years spent in what’s considered generally good health, was 63 for men and 64 for women in 2014/16. But overall life expectancy is increasing at a faster rate, meaning people will on average spend more years in poor health.

Older people are more likely to suffer with chronic conditions, according to a government report. The number of people aged over 90 in the UK has increased by nearly 190,000 since 2002—a 47% rise.

We’ve written more about the ageing population before.

Demand for NHS care is expected to increase, as the Nuffield Trust explains, because of longer lifespans and rising cost of treatments. NHS costs increased by £11bn from 2011/12 to 2016/17. The Nuffield Trust says that the likelihood of ill health is rising across all ages, and quote a study saying that the “impact on the NHS of chronic conditions will amplify the effect of population growth alone.”

“There are nurses who are spending their shifts, their entire shifts in the car park of the hospital because ambulances are parked up and can't get into the hospital.”

Dawn Butler, 11 January 2018

An unnamed nurse told ITV News this week she has sometimes spent whole days treating patients in the cak park of her hospital due to pressures on hospitals over winter. She also claimed increasing numbers of nurses were facing the same situation.

We can’t factcheck individual experiences of accident and emergency services, and there’s no way to know how many nurses are having to take measures like this. But the pressures being talked about echo, to an extent, what we do know about the recent situation facing A&Es in England. We haven’t yet seen detailed data from the rest of the UK on ambulance delays.

These aren’t the only anecdotal reports that have come out of A&Es thi s week. A letter to the Prime Minister from 68 senior A&E doctors listed some of their personal experiences too. According to the doctors these experiences include “patients sleeping in clinics as makeshift wards” and “over 120 patients a day managed in corridors, some dying prematurely”.

Ambulance delays are one key pressure that’s been measured across England in recent weeks.

In the first week of 2018, nearly 16,700 ambulances were delayed by over half an hour after arriving at an A&E department in England, which is one is six of all ambulances that arrived that week. Nearly 5,100—or one in 20—were waiting over an hour.

That varies a lot across the country. The most severe case last week was in Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh, where over half of all ambulance arrivals faced delays over over half an hour and over a quarter of over an hour. Meanwhile a handful of other trusts didn’t experience any such delays.

The picture was similar in the recent Christmas week: overall across England 16,900 ambulances were waiting at least 30 minutes and 4,700 for over an hour.

These delays have worsened compared to earlier in December and November. At the very start of December for example, about one in nine ambulances were waiting over half an hour.

Part of the reason behind these delays is a lack of available beds. More beds were made available last week than there were over Christmas—around 99,000 across England on any given day between 1 and 7 January. On average, 95% of those beds were occupied. We’re planning to write more about how A&Es fared over the winter period soon.

We’ve put more money than ever [into the NHS], 12 billion more than in 2010 when the last government were in charge. We promised another 6 billion.

Dominic Raab MP, 11 January 2018

“It needs, urgently, about 4 billion a year. It’s getting 1.6 and that’s set to go down.”

Gina Miller, 11 January 2018

“I mean, they’re giving the NHS just 1% every year. Under Labour it was 4% every year. It needs more money, not less money.”

Dawn Butler MP, 11 January 2018

It’s correct that spending on the NHS in England has increased by just over £12 billion since 2010, in fact almost £13 billion, and that a further £6 billion was promised at the end of last year.

Part of this £6 billion includes £1.6 billion in 2018/19. This has been welcomed by health experts, but will provide only around half of the £4 billion they have said is needed next year.

Since 2010 the NHS England budget has also increased by around 1% a year on average. Historically, this has been around 4% per year.

Spending on the NHS this coming year

In the Autumn budget last year the government announced that the NHS in England would receive an additional £1.6 billion in 2018/19 (in addition to spending already planned). Factoring in money also announced for more long-term investment in the infrastructure of the NHS this increases to £1.9 billion.

Experts at the King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation think tanks previously estimated that the NHS actually needed a spending increase of around £4 billion that year, based on how spending has increased previously in the NHS and how much its costs are considered likely to increase by.

Following the Autumn budget the King’s Fund said that “While providing some welcome relief for the NHS, the extra funding pledged falls well short of the amount that we estimate is required… the NHS next year will not be able to maintain standards of care and meet rising demand for services.” It also estimates that there will be a gap in the budget of around £20 billion by 2022/23.

Spending since 2010

In 2009/10 health spending in England by the outgoing Labour government was £112 billion (accounting for inflation since then). In 2017/18 the Conservative government plan to spend £124.7 billion. That’s a difference of around £12.7 billion, according to figures from the King’s Fund.

Spending is set to increase by a further £3.3 billion up to 2020/21 when it will reach £128 billion on current plans (again accounting for inflation).

Mr Raab told us that he was referring to the government’s commitment at the Autumn budget to spend an additional £6.3 billion on the NHS in England up to 2022/23. These figures don’t account for inflation and we don’t know what will have happened to NHS spending overall by then.

The total budget for the Department of Health is set to increase by around 1.2% between 2009/10, the last year of the Labour government, and 2020/21. That’s according to the King’s Fund. Since the NHS was established the average increase in spending every year has been around 4%, though the King’s Fund don’t provide specific figures for the Labour years in this research.

When we asked them for more information about Ms Butler’s claim the Labour party pointed us towards the same King’s Fund analysis and separate figures on health spending across the whole of the UK. These show that between 1998/99 and 2010/11 the average spending increase was 6.4% per year and since 2010/11 the increase has averaged 1.4% each year.

Health is a devolved area of spending so the UK government is only directly responsible for exactly how money is spent on this in England. We’re planning on writing more about this soon.