BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Hereford this week. The panelists were: Culture Minister Margot James, Mayor of Greater Manchester and former Labour MP Andy Burnham, Chairman of RBS Howard Davies, former Deputy Mayor of London for Education Munira Mirza and screenwriter and LGBT campaigner Dustin Lance Black.

We factchecked the panel's claims on: Labour's policy on PFI contracts, spending on border controls at Calais over the past three years, how much the UK and France spend on defence and how many nurses from the EU are leaving the NHS.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“If you look at the numbers, it would appear that the big change over the last couple of years has been that we've now got European Union nurses going home rather than coming here… It would seem that part of that apparently, I can't quite believe this, was some new language test was introduced which actually did mean that some people who would otherwise have got in couldn’t get in.”

Howard Davies, 18 January 2018

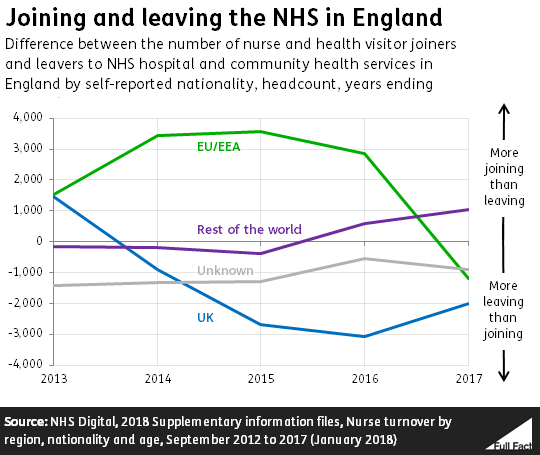

The number of nurses and health visitors from the rest of the EU leaving posts in the English NHS outweighed the number joining in the year to September 2017, the first time this had happened in at least the last five years.

Almost 2,800 nurses and health visitors, from the rest of the EU, joined the NHS and just under 4,000 left. These are headcount figures and count the number of individuals rather than full-time equivalent figures which would give an indication of the hours these staff worked.

The information about where a staff member is from is self-reported—meaning that it could refer to their country of birth, their citizenship or their cultural heritage.

Although we can’t say anything about the reasons why these particular EU nurses left the NHS, we do know something about the reasons why nurses (of all nationalities) left in the year to June 2017.

Around 49% of these nurses resigned voluntarily and of these about half said it was because they were ‘relocating’—although there are no details on where they went. For most of the other 51% of nurses, we don’t even know their reason for leaving.

The number of nurses and health visitors reporting UK nationality leaving the NHS in England has outweighed the number of those joining in each year since September 2013. But there have been more nurses and health visitors from the rest of the world joining the NHS than leaving it since September 2015.

English language testing

Since January 2016 all nurses applying to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) from the EU have been required to sit an English language test. In order to practice in the UK a nurse or midwife must be registered with the NMC.

Nurses from the EU or European Economic Area (EEA) must have reached a certain score in the required English language tests to register with the NMC, this can be either the International English Language Test System (IELTS) or the Occupational English Test (OET).

Alternatively they can register if their nursing qualification was undertaken and examined in English or they have worked for at least one year in a country where English is the first language and were assessed on their English there. These alternative options and the OET test were introduced in November last year.

The same English language requirements must also be provided by nurses from outside the EU/EEA when they register with the NMC. Versions of these requirements have been in place since 2005.

Health think tank, the King’s Fund, cites the introduction of the new English language test as one possible reason for the sharp reduction in the number of nurses from the EU joining the NMC register, along with the result of the EU referendum in 2016. It says “This fall is not driven solely by the vote itself (new English language requirements were also introduced in 2016 for example), but just as with the Francis report, the timing is hard to ignore.”

The Royal College of Nursing has said that evidence suggests “the challenge facing international recruitment in the UK stems in part from a weakening of the overall EEA supply, which is being driven by complex factors including Brexit, worsening conditions for the UK nursing workforce as well as improved economic prospects in the EEA. While IELTS may not be helping this situation, it is unlikely to be the root cause.”

“It's not the first time we’ve paid towards security at Calais. I think we spent about 100 million in the last three years.”

Munira Mirza, 18 January 2018

An unpublished government briefing apparently estimates that around £100 million has been spent on security measures at French border points on the Channel in the last three years. Following an agreement made between the UK and France on Thursday, that figure is thought to now be around £150 million.

We haven’t seen the briefing behind these figures, so we aren’t able to say yet how accurate they are.

The £100 million figure apparently comes from a government briefing

Ms Mirza told us her claim came from a BBC News report which says “The UK government is already thought to have spent more than £100m on security in the area [around Calais] over the past three years.” The BBC told us that their information came from a report by the Press Association, which was apparently based on a government briefing.

The Press Association report says that UK funding towards security measures at French border points is thought to have been over “100 million”—reported elsewhere as £100 million— in the past three years, which would be about £33 million a year.

The report adds that an agreement was made between the UK and France this week for an additional £44.5 million contribution from the UK, bringing the total funding to around £150 million since three years ago. We don’t know if this £44.5 million is to be spent over a single year or over several. The report says the additional funds are to be spent on security fencing, CCTV and “detection technology” in Calais and other French ports on the Channel.

Theresa May confirmed on Thursday that the two countries had agreed “further investment” and “additional measures… increasing the effectiveness of our cooperation”. She said they would “reinforce the security infrastructure”. The sum agreed on Thursday has been widely reported as £44.5 million.

The UK and France have cooperated on border controls for years

Since 2004, the UK and France have cooperated on border controls according to a treaty informally known as the Le Touquet agreement. Both governments yesterday reaffirmed their commitment to its legal framework.

This treaty allows for “juxtaposed controls” where UK border enforcement officers may carry out immigration checks on those seeking to enter the UK at French sea ports (and vice versa). This means the UK border effectively begins at French sea ports on the Channel, and both countries invest in security measures across the border.

Given that the majority of undocumented migrants seeking to cross the channel are believed to enter the UK from France, rather than the other way round, it has been argued by some in France that the treaty is too favourable to the UK, because French authorities have to manage most of the effects of controlling the joint border.

Attention has been drawn to the migrant camp around Calais that was known as the “Jungle”. Several French politicians, including Emmanuel Macron when he was Minister for the Economy, have called for the juxtaposed border arrangement to be ended, citing the Calais migrant camp as a key reason.

The Home Office has published data too

In April 2017, the Home Office responded to a Freedom of Information (FOI) request asking how much it had “spent since 2010 to deter illegal immigration in Calais and the surrounding region.”

The government response says that it spent £316 million from 2010/11 to 2015/16. The sum was £40 million in 2013/14, £49 million in 2014/15, and £112 million in 2015/16.

It’s unclear how much of this spending is counted within the £150 million spent in the last three years, reported by the Press Association.

The Home Office figures cover “day to day activities” including “passport checks on all passengers” and “searching for illicit goods”, which UK border officers carry out on French soil.

The spending also covers “recent investment to reinforce security through infrastructure improvements at Border Force’s controls in Northern France”, as well as “stopping and deterring illegal immigration” through a range of “wider activity”.

The large increase in spending between 2014/15 and 2015/16 is put down to “a combination of increased migrant pressures in Calais, new operational and technological improvements at the juxtaposed controls and improvements to infrastructure in the region.”

The spending is part of a joint commitment between the UK and France to manage the border between the two countries.

“We interact with the French on so many levels, defence and security are key. Both countries are the predominant defence countries in terms of investment and spend across Europe.”

Margot James MP, 18th January 2018

The UK and France are the highest spenders on defence in Europe.

Eurostat publish figures on government spending by European countries in euros. The latest comparable figures are for 2015, and show that the UK had the highest defence spending in Europe that year, spending just under €55 billion. France was second, spending €38 billion, and Germany third with €31 billion.

Relative to the size of each country’s GDP, Greece spent the most in 2015 (2.7% of GDP), followed by the UK (2.1%), Estonia (1.9%) and France (1.8%). As a proportion of each country’s total government spending, the UK spent the most (5% of the total), followed by Greece (4.9%) and Estonia (4.7%). Measured this way France was much further down the league table, in 9th place at 3.1%.

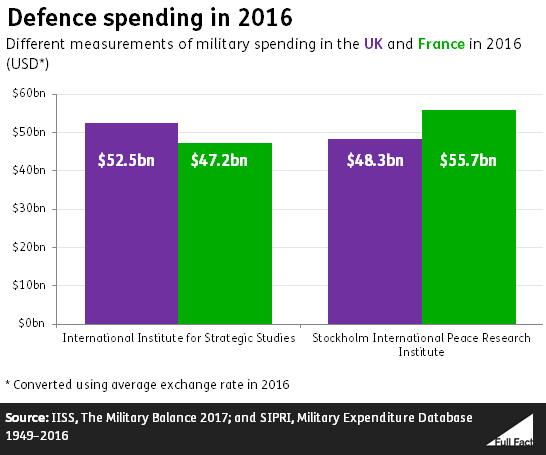

The International Institute for Strategic Studies’ (IISS), an international affairs think tank, has more recent figures covering 2016 and it also found the UK had higher defence spending than any other European country. France and Germany came in second and third respectively.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), another think tank, has slightly different findings. It shows that France had the highest defence spending in 2016, the UK was second, and Germany third.

We’ve written about the differences between the SIPRI and IISS data in the past. The problem is there’s no single definition of military expenditure. When we spoke to SIPRI in 2015 it suggested its calculation of France’s spending is higher because it includes the paramilitary Gendarmerie while other sources do not. We’re checking with them whether or not this is still the case.

Andy Burnham: “We shouldn’t have been told ‘PFI or no hospital’ [when Labour was in government].”

David Dimbleby: “Who told you that?”

Andy Burnham: “That was the Treasury.”

Howard Davies: “Treasury officials have never liked the PFI. I was a Treasury official myself. They never liked PFI.”

BBC Question Time, 18 January 2018

We can’t say what Treasury officials may have thought or said about Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) off the record, but there’s still plenty of evidence for the position it has taken publicly.

PFIs were seen as the only viable option for funding construction projects among some public bodies in the 2000s—and were widely used across government departments compared to today—which is the point that Mr Burnham is getting across.

The Treasury’s official guidance has stressed that PFIs should only be undertaken if they’re seen as delivering value for money, but it’s clear that many public bodies may have been taking other considerations into account as well.

What are private finance initiatives?

A PFI normally happens when a public body wants to build something like a school, hospital or road, and decides to fund it through private finance rather than with money it normally gets from the Treasury.

When PFI isn’t used—in fact more than 90% of the time—the Treasury raises money itself through taxes or borrowing and allocates a budget to the public body. The public body then pays a contractor to build the project.

In a PFI, the government doesn’t pay the upfront cost. A private finance company raises the money, mainly through its own borrowing, and also tends to be responsible for some of the design, operation and maintenance of the project. The public body is effectively the purchaser of the services, leasing from the private provider.

The government ends up paying for the project later, in annual payments over a period of typically 25 to 30 years.

PFIs tend to cost more than the alternatives, so the official test is whether they deliver value for money

As the National Audit Office (NAO) summarised yesterday: “In general, HM Treasury discourages public bodies from borrowing privately”.

The Treasury’s own guidance says that: “Public sector organisations may borrow from private sector sources only if the transaction delivers better value for money for the Exchequer as a whole. Because non-government lenders face higher costs, in practice it is usually difficult to satisfy this condition unless efficiency gains arise in the delivery of a project (eg PFI)”.

PFIs do usually cost more in the long-run than in publicly funded projects. That’s mainly because it tends to cost private companies more to borrow money than it does for the government, and the interest on the annual repayments adds up to a lot more over several decades.

At the same time, there are potential advantages to PFIs. One of the main perceived benefits is that they transfer the risks associated with construction—like running over time or budget—on to private companies, because they’re the ones funding the construction upfront.

The evidence on whether PFIs deliver more efficient, high quality services isn’t clear-cut. Both the NAO and the Institute for Government think tank have highlighted a lack of data on the benefits and drawbacks of using PFIs. The NAO presents some recent research showing a mixed picture.

But PFIs were still widely seen as the “only game in town”

If PFIs were chosen based on value for money in theory, there’s a lot of evidence this wasn’t always the basis in practice.

The House of Commons Treasury Committee found in 2011 that in many cases: “there is an incentive for both HM Treasury and public bodies to present PFI as the best value for money option as it is often the only avenue for investment in the face of limited departmental capital budgets.”

Several public bodies told the Committee that PFIs were seen as “the only game in town” in the 2000s, due to the lack of alternative sources of funding.

Another reason PFIs may have been popular is the way they appear—or don’t—in the government’s accounts. Most PFI debt the government takes on is recorded as off-balance sheet—in other words it doesn’t show up alongside most other spending or debt figures in the national accounts.

As the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) commented in 2014: “this generates a perception that PFI has been used as a way to hold down official estimates of public sector indebtedness for a given amount of overall capital spending, rather than to achieve value for money.”

These considerations aren’t supposed to be part of the decision to sign up to a PFI, according to the Treasury itself and others. In practice though, it does seem to have been an incentive.

The Treasury Committee heard from an expert in the construction industry in 2011 that there were “clear examples” in the 2000s where “there was a distortion in the structuring of deals in order to achieve a particular accounting treatment”, although he went on: “hopefully, we are moving beyond the world in which the off balance sheet tail was wagging the value-for-money dog”.

In interviews last year the Institute for Government heard cases where the Treasury had encouraged the use of PFIs for this reason. However, given the more limited use of the finance since 2012, it commented that “the strength of this accounting pressure is therefore questionable”.