Employment: Is employment up only because of zero hours contracts?

In this series of articles we try answer common questions about whether we can trust employment statistics, and go beyond the headline figures to assess the health of the labour market more comprehensively.

We’ve already looked at the extent to which we can actually trust the quality of the employment and unemployment statistics and whether more people are dissatisfied with their hours.

This piece looks at whether there’s any truth in the critique that the rise in employment is down to a rise in insecure work—primarily an increase in the number of people on zero hours contracts. Zero hours contracts do not guarantee a worker a minimum number of hours, and the worker is “on call” to work as and when they are needed.

More people may be in work, the argument goes, but this work is unstable and not guaranteed long-term, so it doesn’t provide the security that normally comes from being employed. Criticisms of zero hours contracts have been made repeatedly by Jeremy Corbyn and others in the Labour Party.

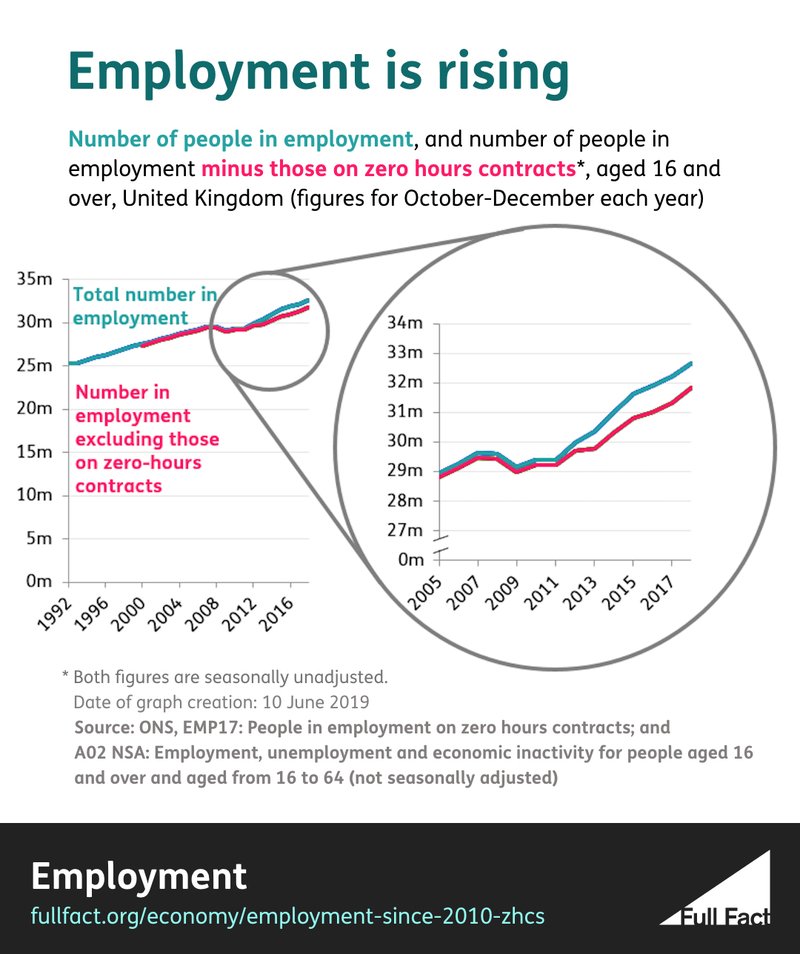

There certainly has been a significant rise in the number of people working on zero hours contracts since 2010. However, even if we were to discount all these people from the employment statistics, employment would still be at record levels today.

This shows that, while the number of zero hours contracts has been increasing, this has been alongside an increase in the number of people working on more stable contracts too.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Official figures for zero hours contracts have risen sharply since 2011

Before we look at the numbers in detail it’s important to note that critiquing the record employment rate citing the rise in zero hours contracts assumes that these contracts are sufficiently different from other forms of work (in a negative way) that they should be either split out from, or entirely discounted from, general employment statistics.

The evidence does suggest that they aren’t popular with workers: one survey suggests the majority of workers on these contracts (66%) would prefer to work on a guaranteed-hours contract. But that leaves a sizeable minority for whom zero hours contracts are either as preferable as, or more preferable than, guaranteed-hours contracts.

In order to address this argument, we’ll look at whether the total employment rate is up because of zero hours contracts.

Shortly after the Coalition government took office in 2010, the number of people on zero hours contracts rose significantly. It reached a peak of around 900,000 at the end of 2016 and 2017, and has since fallen back slightly, to around 850,000 at the end of 2018.

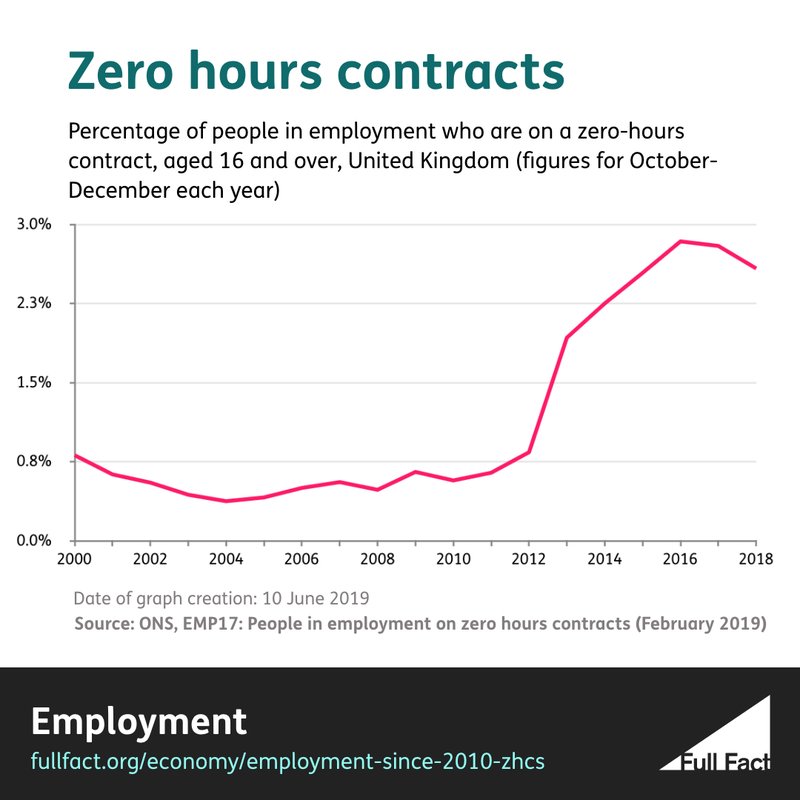

The proportion of the workforce on zero hours contracts also increased in that period. The level hovered between 0.4% and 0.8% from 2000 to 2012, before rising to a peak of 2.8% in 2016.

These figures aren’t perfect. It’s possible that this rise may be overestimated, because the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) survey relies on people self-reporting as being on a zero hours contract, from a list of options.

The ONS says: “The upward trend that we saw [in the number of zero hours contracts] between 2011 and 2016 was likely to have been affected by greater awareness and recognition of the term “zero hours contract.” In other words, some people might have already been on a zero hours contract, but only realised that was the technical term for it once everybody started talking about the issue.

Judging when people might have become more aware of an issue is tricky. Parliamentary records show that mentions of zero hour contracts took off in 2013 and similarly Google trends shows that searches increase significantly at the same time — a point at which the official figures had already begun trending upwards, but before the large spike of the mid-2010s.

However because people still need to positively identify themselves as being on a zero hours contract, the overall number of people working on them may be underestimated, even while the steepness of the rise may have been overestimated.

Also zero hours contracts do not cover everything we might consider “insecure” work, such as seasonal or agency work. So when we look at “insecure” work by focusing just on zero hours contracts, there’s going to be some people who aren’t captured in the statistics.

We would still have record employment without zero hours contracts

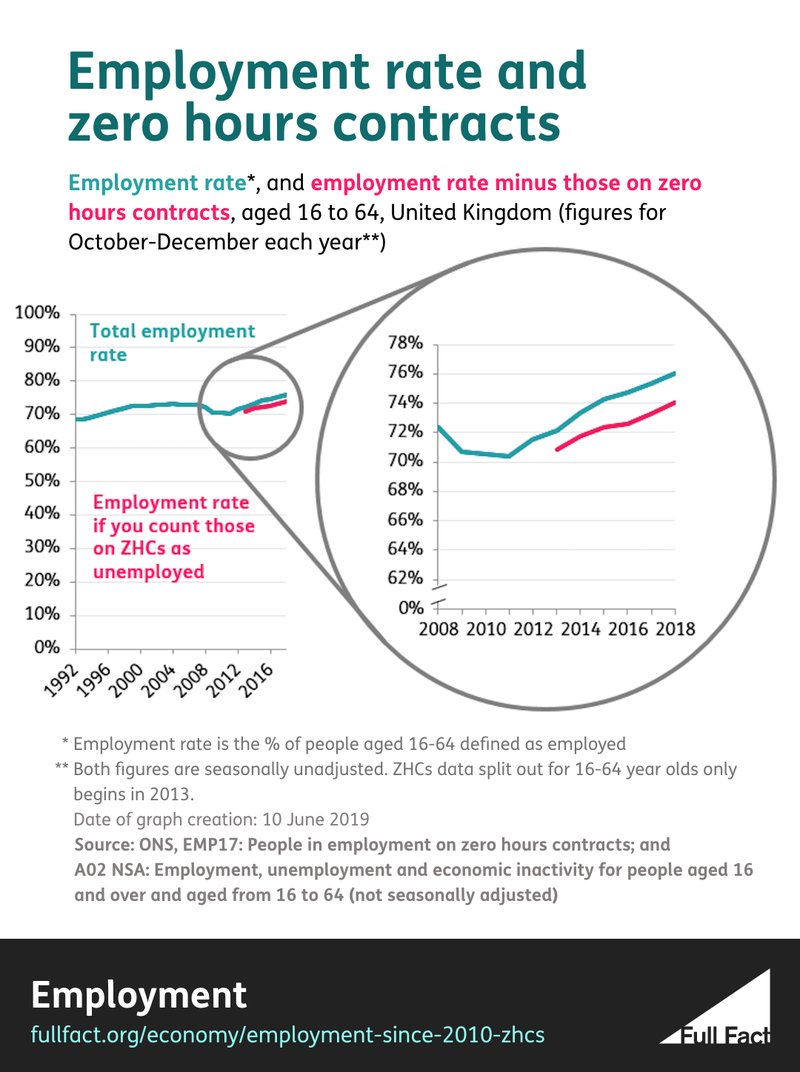

Putting those caveats aside, the employment rate (the proportion of people aged 16-64 who are in work) would still be at a record high even if every worker on a zero hours contract was excluded from the data.

If we were to count people employed on zero hours contracts as unemployed, the employment rate for those aged 16-64 at the end of 2018 would have been 74.1%. That is higher than the employment rate (including people on zero hours contracts) at any time before 2015.

The raw number of people in employment is also at a record high whether or not you count people on zero-hours contracts in the figure.

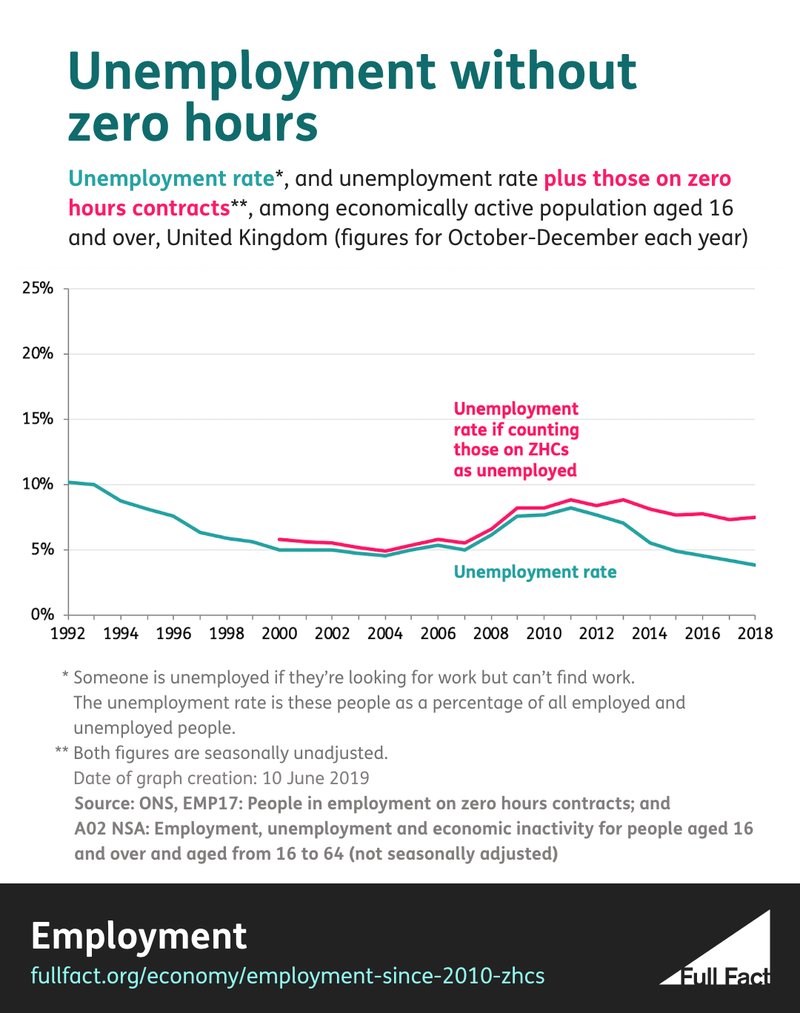

The unemployment rate is not at a historic low if you discount zero hours contracts

On the other hand the unemployment rate wouldn’t be at its lowest since the 1970s (a line the government is also fond of saying) if it wasn’t for people in zero-hour contracts.

If you counted all people on zero hours contracts as unemployed, then the unemployment rate would only be at its lowest since 2009 (though, as mentioned, this may be affected by more people being aware of zero hours contracts in recent years and so increased reporting of people being on these contracts.)

The unemployment rate is not just the mirror-image of the employment rate. The employment rate tells us what percentage of people aged 16-64 are in work. The unemployment rate tells us what percentage of people don’t have a job, among everyone in the UK aged 16 and over who wants work.

In summary then, the employment rate isn’t at a record level because of the rise in zero hours jobs. It would be at a record level even if people on zero hours contracts were excluded from the figures.

It’s possible however that the unemployment rate wouldn’t be at a record low without the growth in zero hours jobs. But this depends on how much of the recent growth in people on zero hours jobs is genuine, and how much is down to increased reporting of these contracts as mentioned.

Regardless, the unemployment rate would still have fallen since 2010, even if zero hours jobs are discounted.

These aren’t the only factors you might want to consider though. You might want to ask what working conditions are like for this growing group of people employed on zero hours.

As mentioned, there’s evidence that the majority of people on zero hours contracts are not happy with the stability that contract gives them, and there’s also evidence that they do not receive benefits received by other workers. Only 12% of zero hours workers told a survey commissioned by the Trades Union Congress that they got sick pay, 43% didn’t get holiday pay, and half did not get written terms and conditions.

In our next and final article, we’ll look at what’s happened to wages since 2010, and what that means for employment figures.

More from this series:

- Why don't people trust employment statistics?

- Is employment up because the government is fiddling the statistics?

- Is employment up because work is being spread more thinly, with people working fewer hours?

- Is employment up because more people are working on unstable zero-hours contracts?