Theresa May's party conference speech, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

"Thanks to George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse, over the past year, foreign direct investment in the North has increased at double the rate of the rest of the country."

Theresa May, 5 October 2016

It’s not the first time that Theresa May has made this claim. But we weren't sure whether it referred to the total value of foreign investment, the value of new investments or just the number of investment projects.

We contacted the Conservative party who told us that the Prime Minister was referring to the increase in the number of deals being made in the North, compared to the UK as a whole.

It’s correct that the total number of foreign direct investment deals made in the UK increased by 11% in 2015/16, compared to the previous year. Meanwhile, the government has said the number of deals in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and Humber regions increased by 24%—so about double the rate.

But that doesn’t tell us how much each of these investment deals was worth. Some of them might have been very large investments, others small. A change in the number of investment deals might not mean that there’s been an identical change in the value of money invested.

The Office for National Statistics told us that they don’t publish estimates for the value of foreign direct investment particular regions. So we don’t know how the value of foreign direct investment in different regions compares, or how it changes from year to year.

Update

This factcheck was updated on 11 October 2016 after the Conservative Party responded to our enquiry.

“It’s just not right, for example, that half of people living in rural areas, and so many small businesses, can’t get a decent broadband connection.”

Theresa May, 5 October 2016

Regulator Ofcom says that the typical household needs a minimum broadband speed of 10Mbit/s—the “tipping point beyond which most consumers rate their broadband experience as ‘good’”.

Just under half of rural properties (around 1.5 million) can’t access that speed, according to its report. Only 4% of urban properties have speeds less than 10Mbit/s.

Ofcom says that’s because of the longer lengths of copper wire between rural properties and the source of their internet connection.

It also says that slow broadband is a significant problem for many smaller businesses across the UK.

A separate study last year found that just under half of people living in remote rural areas said their internet connection was fast enough, and more than half had an average speed less than 6.3Mbit/s. At that speed the report said it would take about a minute to download 10 songs, or four minutes to save 200 photos.

Ofcom’s maps show broadband availability by area in 2013.

Image courtesy of Sean MacEntee

“the Conservative party... investing an extra £10 billion in the NHS – more than its leaders asked for”

Theresa May, 5 October 2016

This claim shouldn’t be taken at face value.

NHS England said in 2014 that £8 billion was the minimum it needed by 2020 to fill the £30 billion estimated NHS funding gap. That relies on the NHS finding the remaining £22 billion in savings.

The government’s commitment of £10 billion, rather than £8 billion, isn’t as generous as it sounds. The £8 billion requested was to cover a five year period. The £10 billion counts funding for an extra year—the last year of the previous parliament—which wasn’t covered by the NHS’s spending options anyway.

The NHS is set to get about £8 billion over the course of this parliament, taking inflation into account.

It’s also not all of what the NHS asked for. The NHS said that its ambitions for savings were only possible “provided we take action in prevention, invest in new care models, sustain social care services, and… see...wider system improvements”.

The government’s £8 billion commitment refers specifically to the NHS England budget. Outside of this, spending on public health is expected to fall over this parliament, and spending on social care is expected to continue to fall short of what’s needed.

That means total health spending in England—including areas such as public health and social care as well as NHS England—will only rise by £4.5 billion over the same period, according to leading healthcare think tanks.

“If you are from a black Caribbean background, you are three times more likely to be permanently excluded from school than other children.”

Theresa May, 5 October 2016

This is correct, comparing black Caribbean pupils to all pupils.

Black Caribbean pupils were about three and a half times more likely to be permanently excluded from state schools than all students in 2014/15. These figures are for primary, secondary and special schools.

250 black Caribbean pupils were permanently excluded in 2014/15, making up 0.28% of all black Caribbean pupils in England. Across all ethnic groups 5,770 pupils were permanently excluded or 0.08%.

The difference was bigger for boys than girls. Black Caribbean boys were almost four times as likely to be excluded compared to all male students; black Caribbean girls were twice as likely.

Black Caribbean students were also twice as likely to be permanently excluded as black students as a whole.

Gypsy/Roma students and pupils who were travellers of Irish heritage had the highest rate of exclusion: they were both six times more likely to be excluded than all students. But the Department for Education said these figures should be “treated with some caution” since these groups of pupils are quite small.

Asian students, particularly those of Indian descent, were the least likely to be permanently excluded.

Image courtesy of buck82

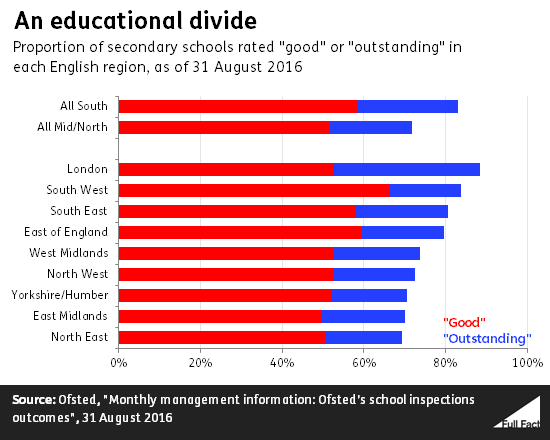

“If you live in the Midlands or the North, you have less chance of attending a good school than children in the South.”

Theresa May, 5 October 2016

This is correct according to school inspectors Ofsted. There’s only a slight difference for primary schools but a significant one when it comes to secondary schools.

The head of Ofsted, Sir Michael Wilshaw, said late last year that “there’s a growing divide between the performance of secondary schools in London and the South, and the performance of secondary schools in the Midlands and the North”.

Ofsted rates schools one of “outstanding”, “good”, “requires improvement” or “inadequate”.

Some 83% of secondary schools in the South inspected by Ofsted have been rated “good” or “outstanding” compared to 72% of secondary schools in the North and Midlands.

For primary schools, the equivalent figures are 89% for the North and Midlands, and 90% for the South.

Image courtesy of James S Clay