Migration and welfare benefits

- Most non-EU nationals who are subject to immigration control are not allowed access to "public funds" (such as jobseekers' allowance or tax credits), although they can use public services like the NHS and education.

- EU citizens who are working have similar access to the benefits as UK citizens. For jobseekers or people not working, the rules for determining eligibility can be complex and vary depending on the type of benefit in question.

- The current government has introduced various restrictions on European Economic Area (EEA) citizens' access to benefits. Their impacts on total welfare spending are hard to quantify but are not likely to be large.

- Foreign born people are less likely to be receiving key Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) out-of-work benefits than the UK born, but more likely to be receiving tax credits.

- It is unclear whether current or proposed welfare restrictions would reduce future immigration.

Most non-EEA nationals who are subject to immigration control are not allowed access to "public funds" (such as jobseekers' allowance or tax credits), although they can use public services like the NHS and education.

Most citizens of non-EEA countries who come to live in the UK have "no recourse to public funds" in the initial years after they arrive, when there are still time limits or other conditions on their authorization to remain in the UK. This means that they are not eligible for benefits such as jobseekers' allowance, disability allowance, tax credits, or housing benefit.

There are some exceptions, such as people who have been granted humanitarian protection but do not have permanent residence. Claims for tax credits may be made by couples if only one partner would not be able to claim in their own right because they have no recourse to public funds.

"Public funds" do not include public services like schools or the National Health Service. However, from April 2015 an NHS Surcharge of £200 per applicant and dependent (or £150 in the case of a student) for each year of a visa is now added to the normal cost of the visa for non-EEA citizens.

Non-EEA citizens who initially have no recourse to public funds become eligible for them when they are granted permanent residence (for most admission categories eligible for settlement this requires five years of legal residence).

Asylum seekers are not eligible for welfare benefits while their claims are pending, but may be given less generous financial support through a separate Home Office programme. They become eligible for public funds if they are granted refugee status.

EU citizens with jobs have similar access to the benefits as UK citizens. For jobseekers or people not working, the rules for determining eligibility can be complex and vary depending on the type of benefit in question.

EU law does not allow member states to impose on EEA citizens the same restrictions as the UK currently operates for non-EEA nationals. Eligibility criteria for EEA citizens are quite complex and depend on a range of factors such as whether they are, or have been, in "genuine and effective work" or have a "genuine chance" of being hired.

An EEA citizen who arrives without a job and is still looking for work cannot receive means-tested jobseekers' allowance, child tax credit or child benefit within the first three months, under new regulations that came into force during 2014. These jobseekers must also pass the "habitual residence test" in order to claim. This test considers various factors including the measures they have taken to establish themselves in the UK and find work here.

An EEA citizen who moves to the UK and is determined to be a "worker" is immediately eligible for in-work benefits like tax credits and housing benefit. However, their work must be considered "genuine and effective".

The current government has introduced various restrictions on EEA citizens' access to benefits. Their impacts on total welfare spending are hard to quantify but are not likely to be large.

Various measures have been introduced since 2013 to restrict welfare access for EEA citizens who are not working. In particular, new measures mean that EEA jobseekers:

- Cannot claim means-tested Jobseekers Allowance (JSA), child benefit, or child tax credit within the first three months of arriving in the UK.

- Lose eligibility for JSA if they are still looking for work after a further three months, unless they can give 'compelling evidence of a genuine prospect' being hired, such as a written job offer.

- Cannot claim housing benefit.

There were also two changes to the processes of determining whether applicants meet existing eligibility criteria. This included an "improved electronic tool" for determining whether someone is "habitually resident", and a new policy of scrutinizing applications more closely if a person's claim to have gained eligibility for benefits because of their current or previous employment was based on work that earned them less than the threshold at which employees start paying National Insurance contributions (currently £155 per week).

The impacts of these changes are hard to quantify because accurate data on the numbers of people that fall into these very specific categories of claimants are not published. The cost savings from the changes are likely to be small in the context of total welfare bill, because: they only affect out-of-work benefits; EU migrants represent a small share of out-of-work benefits claims (as described below); and the measures only apply to a subset of EU migrants.

One impact assessment did estimate expected savings from the change to housing benefit eligibility at £10m per year, although this calculation required assumptions based on imperfect data on the number of claims that the new policy would prevent. These projected savings should be seen in the context of an overall annual housing benefit bill of approximately £24 billion.

Some legal analysts have argued that some of the new restrictions might infringe EU law, and could thus be vulnerable to legal challenges.

Foreign-born people are less likely to be receiving key DWP out-of-work benefits than the UK born.

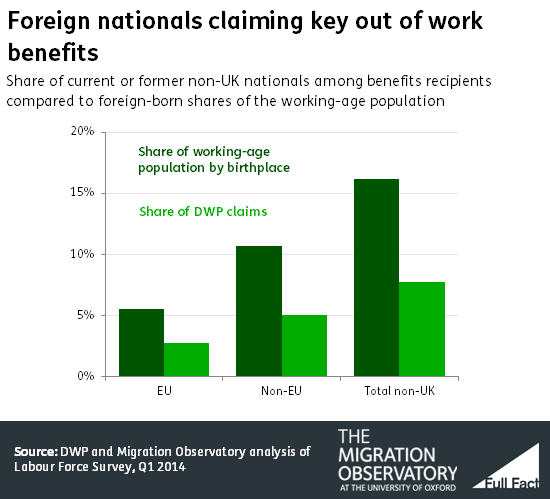

In February 2014, 7.7% of working-age individuals receiving 'key out-of-work benefits' were non-UK nationals at the time that they registered for a national insurance number (NiNo). The largest categories were jobseekers' allowance and incapacity benefits. The DWP figures do not include housing benefit, which is paid to working people as well as those out of work.

To determine whether migrants are over- or under-represented among benefits recipients, we can compare the DWP statistics to the share of migrants in the working-age population as a whole. We follow the approach used by the Migration Advisory Committee and compare the DWP statistics to the foreign-born population in the Labour Force Survey.

This comparison is only approximate, because migrants are counted slightly differently in the two datasets. The LFS measure includes all foreign-born people, including both noncitizens and naturalised citizens. The DWP statistics include both noncitizens and naturalised citizens who registered for a NiNo before they naturalised; people who naturalised after registering will not be counted.

People born outside of the UK (including—like the DWP data—those who subsequently became citizens) made up 16.2% of the working-age population in the first three months of 2014, according to Migration Observatory analysis of the Labour Force Survey. This suggests that the foreign born are underrepresented among out-of-work benefits recipients.

Both EU and non-EU migrants are underrepresented among the key out-of-work benefits recipients when compared to the share of the population born abroad. Claimants from new EU member states have increased in recent years but remain a small share of the total, rising from 0.5% of claimants in February 2011 to 1.3% in February 2014.

People born abroad are more likely to receive tax credits than people born in the UK

Tax credits are designed primarily to supplement the incomes of people who are working but are on low incomes.

Determining the rate at which migrants claim tax credits is difficult. This is because tax credits are awarded to family units (that is, to a single person or a couple) rather than purely to individuals. A particular problem is deciding whether couples that include one UK and one non-UK citizen should be counted as "migrant" benefit recipients.

HM Revenue and Customs has reported data on tax credit payments to families where at least one adult was a non-EU national when they applied for a national insurance number. In March 2014, there were an estimated 317,800 families in which at least one adult was or had been an EU national, and 421,100 where one partner was or had been a non-EU national.

These families will include mixed UK- and non-UK citizen couples, as well as benefits going to naturalised UK citizens. As a result, the data should not be used to assess welfare policy proposals that would affect smaller groups of migrants (such as recently arrived non-citizens).

HMRC estimated that the total amount paid to families that included at least one current or former non-citizen adult was £5.17bn, suggesting that among such families who received tax credits, the average payment was about £7,000 per year.

In the first quarter of 2014, foreign born people of working age were more likely to report receiving tax credits (15%) than the UK born (11%), according to Migration Observatory analysis of the Labour Force Survey. Similar shares of EU born and non-EU born people reported receiving tax credits (14% and 15% respectively).

The largest gap in rates of claiming was between people born in countries that joined the EU before vs. after 2004. 18% of people from new member states reported receiving tax credits compared to 8% from the pre-2004 members.

This survey relies on self-reported data that is known to undercount benefit recipients. However, if we assume that undercounting is the same for all nationality or country-of-origin groups, it can be used to compare rates of take-up.

It is unclear whether current or proposed welfare restrictions would reduce future immigration.

There is no direct evidence on whether welfare has acted as a "magnet" encouraging migrants to come to the UK, and such evidence would be hard to gather.

Because most non-EU citizens are initially ineligible for benefits, benefits are unlikely to be a meaningful draw for significant numbers within this group. EU citizens can access benefits more quickly, but the majority are working so out-of work benefits are unlikely to be a draw for them either (the unemployment rate among EEA nationals was 5.2% in the last three months of 2014, according to Migration Observatory analysis of the Labour Force Survey).

In-work benefits are immediately available to workers from elsewhere in the EU. While the availability of jobs is thought to be the prime factor in migrants' decisions to move, it seems plausible that just as potential migrants take into account wage levels, they may also take account of the possibility of in-work benefits. Some analysts have argued that the financial incentive to migrate would therefore be decreased if these benefits were restricted.

In practice, however, it is unclear how significant the effects of such a policy would be on the number of people choosing to migrate. Only a small share of the EU born report claiming tax credits (14% in 2014, as described earlier). This suggests that the number of people whose initial migration decision might be affected by the immediate availability of tax credits is only a small share of the total.

Note that additional restrictions on benefits for EU citizens might need to be negotiated with the European Union rather than simply introduced by the UK parliament.

This briefing was written by Madeleine Sumption and William Allen of the Migration Observatory in collaboration with Full Fact. Thanks to Yvonni Markaki for analysis of the Labour Force Survey data, and to Charlotte O'Brien, Michael O'Connor, Alan Manning, Bridget Anderson and Carlos Vargas-Silva for extremely helpful comments on an earlier draft. This work has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation but the content is the responsibility of the authors and of Full Fact, and not of the Nuffield Foundation.