Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Prime Minister’s Questions this week included claims on taxing the super rich, debt interest, tax avoidance and shared parental leave.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“We have taken action collectively as a Government over the last few years since 2010 when we first came in, and we have secured almost £160 billion in additional compliance revenues since 2010”

Theresa May, 1 November 2017

This is correct according to HM Revenue and Customs’ own estimates, but ‘secured’ here is a very broad term—a large part of it covers money the government thinks it will get in future as a result of actions it has already taken, rather than what it has actually saved so far.

HMRC has a compliance function that tries to stop the loss of money through tax evasion and avoidance. Each year they try to prevent some money being lost before it happens, recoup some of the money they do lose, and through those actions try to prevent losses in future years. The money they estimate they have secured through all these activities is called their “compliance yield”.

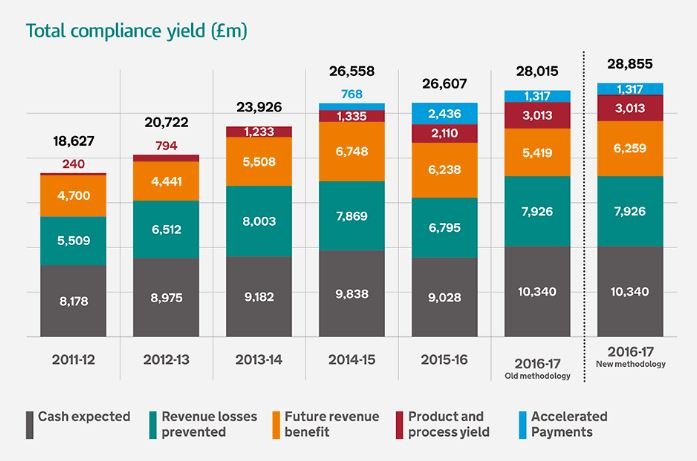

You get a figure of around £160 billion by adding up HMRC’s total compliance yield for every year since 2010/11—roughly the first full year of the coalition government.

Those figures—at least the ones since 2011/12—are provided in a chart in HMRC’s annual report. The 2010/11 figures are in an older report, and are known to be of worse quality.

Apart from the ‘new methodology’ 2016/17 figure, the total amount of money being shown in each year isn’t what HMRC thinks it actually made in extra revenue for those years. It’s including the money HMRC thinks it will make in future years, up to 2021/22.

That’s because part of what HMRC estimates it has secured each year is called “future revenue benefit”, which is included in the chart. This is an estimate of the future benefits of the compliance work already undertaken, spread out over about five years.

So when HMRC and the Prime Minister say £160 billion has been “secured”, they’re actually talking about expected revenue for the future as well, not just what’s actually been realised so far.

HMRC sets out separately how much money it thinks was actually secured in these ‘future revenues’ each year since 2011/12.

That means that the actual amount secured so far, excluding the expected benefits to come, amounts to just under £150 billion, with the rest expected over the next five years, as a result of action that’s already been taken.

Some of the other money isn’t certain either

Measuring the effect of the government’s tax compliance activities isn’t straightforward. HMRC describes it as “a complex hybrid of measures, calculated in different ways and covering different time periods, which are designed to reflect the breadth of HMRC’s compliance activities.”

The independent National Audit Office is satisfied that “HMRC has robust processes in place for estimating and reporting the value of the yield that it has generated through its compliance activities”, but notes there is still uncertainty in the estimates.

The largest part of the compliance yield each year is called “cash expected”, which is what HMRC estimates it is likely to recoup in lost revenues that year. It’s adjusted to take into account that it won’t be able to collect every sum it identifies.

A large sum is also is made from preventing losses before they happen. This is where HMRC estimates its own actions have prevented losses that could otherwise have occurred, like stopping fraudulent repayment claims, according to HMRC.

You’ll often also read about governments trying to close “tax loop holes” by introducing new laws or putting tighter systems in place. These make up a smaller part of the money that’s recouped in the HMRC figures—about £3 billion last year.

“The amount of tax paid by the super-rich in income tax has fallen from 4.4 billion to 3.5 billion since 2009.”

Jeremy Corbyn, 1 November 2017

The amount of income tax paid by “high net worth individuals” fell from £4.4 billion in 2009/10 to £3.5 billion in 2014/15, according to figures from a National Audit Office (NAO) report from November 2016.

But changes to income tax rates in 2010 mean that 2009/10 isn’t a good year to compare with as the tax take was higher than it otherwise would have been, according to HMRC.

The tax collectors say: “The introduction of the additional rate of income tax in 2010-11 led to forestalling of income brought forward into 2009-10. When this rate was subsequently reduced in 2013-14, individuals delayed income from previous years. Individuals received notice of this change a year in advance. These changes heavily impacted on receipts over the period.”

HMRC also says that changes to the economy have had an impact on the amount of tax received.

Who are the “super-rich”?

The report uses HMRC’s definition of a “high net worth individual”, as anyone with wealth of more than £20 million including all their property, stocks and savings and excluding any debts.

HMRC said there were 6,500 high net worth individuals in the UK at the start of 2015/16. That's 0.02% of taxpayers, according to the NAO.

HMRC has recently revised the definition to include anyone with wealth over £10 million. That adds another 2,000 people to the “super-rich” category.

The amount of income tax paid by high net worth individuals fell from £4.4 billion in 2009/10 to £3.5 billion in 2014/15, according to the NAO.

But the NAO also give a note of caution. It says HMRC put some of the changes in the tax collected down to changes in the economy and to rate of income tax collected.

The NAO says “HMRC’s analysis of income tax liabilities over this time has found that the tax paid on income over £150,000 is: higher than it would otherwise have been in 2009-10 as people brought forward income to that year; lower than it would otherwise have been following the introduction of the 50% rate between 2010-11 and 2012-13; and higher again in 2013-14—when the rate was reduced to 45%—as people delayed income from previous years.”

So we don’t know what the trend of income tax receipts would have been without these unusual shifts in incomes following the rate changes since 2010 and in the economy.

That means comparing the tax take in 2009/10 to 2014/15 isn’t a fair comparison.

Income tax receipts have increased for taxpayers overall

A committee of MPs looking into taxes collected from the super-rich noted that, at the same time as income tax receipts from high net worth individuals fell by 20%, income tax from all taxpayers increased by 9% or £23 billion. In their response to the committee HMRC said the changes to the economy and tax rates were behind this.

HMRC set up a specialist unit dedicated to collecting tax from high net worth individuals in 2009.

HMRC told the committee it estimated that the unit raised £416 million more than was voluntarily declared by high net worth individuals.

“Today we spend nearly £50 billion in payments on interest to those we have borrowed from as a result of the legacy of the Labour party. That is more than the NHS pay bill, it is more than our schools budget, more than we spend on defence, as a result of the record we were left by Labour in government”

Theresa May, 1 November 2017

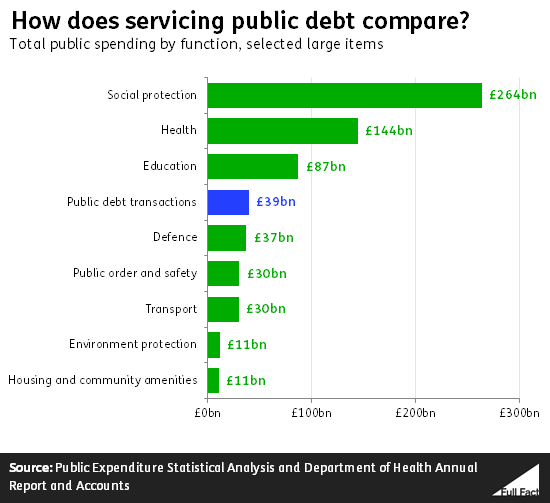

The UK government’s debt interest bill was about £48 billion in 2016/17, but that’s not the most meaningful figure to be using.

The government effectively pays some of that to itself. As we’ve covered before, almost a quarter of government debt is owned by the Bank of England, which pays the profit back to the Treasury.

The total amount of spending on what are called ‘public debt transactions’ amounted to £39 billion in 2016/17, once you take off what the Bank of England owns.

This is higher than spending on defence and primary education, but slightly lower than spending on secondary education.

It is also lower than the NHS pay bill. The Department of Health’s annual report shows that £48 billion was spent on permanent staff costs in 2016/17, increasing to £54 billion when including other staff.

“Self-employed people are not eligible for shared parental leave. This places the burden of childcare on the mum, denying fathers financial support and bonding time with the child.”

Tracy Brabin MP, 1 November 2017

Ms Brabin is fundamentally correct.

The rules around the pay and leave parents can qualify for when having a child are complicated.

Self-employed mothers might qualify for maternity allowance, worth up to £140.98 a week, and using this can take time off to care for their child if they are able and want to. They can also exchange this for shared parental leave and pay for their partner, if he is employed and eligible. But they have to give up their maternity allowance to do so.

Self-employed fathers aren’t eligible for any shared parental leave or pay.

Parental leave and pay

Eligible women are entitled to up to 52 weeks of maternity leave when they have a baby—this can start before the baby is born. Eligible men can get one or two weeks of paternity leave after the baby is born.

Women who are eligible can choose to trade in their maternity leave for shared parental leave. If they’re both eligible the couple then have up to 52 weeks of leave, minus any weeks of maternity leave have already been taken. This can then be split between them and their partner as they see fit—so one partner might take half the time, and the other take the rest.

The idea behind the regulations is to allow parents to share more time with their child early on, let fathers spend more time with their child and “to create more equity in the workplace and reduce the gender penalty resulting from women taking long periods of time out of the workplace on maternity leave”.

Eligible parents can get statutory maternity pay or paternity pay. Women are paid this for 39 weeks—six weeks at 90% of their usual weekly earnings and 33 weeks at 90% or around £140.98 a week whichever is lower. Men are also paid a 90% rate or £140.98 a week for the length of their paternity leave.

Eligible mothers can swap their maternity pay for shared parental pay. Like shared parental leave this can be split between both parents.

Self-employed people don’t qualify

Self-employed men and women aren’t eligible for paternity, maternity or shared parental leave or pay as only people with an employer can get those.

Self-employed women can be eligible for maternity allowance, a substitute payment, set at £140.98 a week for 39 weeks. Using this they may be able to take time off to care for their child.

Employed women may get maternity leave but can’t transfer any shared parental leave or pay to their partner if the man is self-employed. If a man is employed and his self-employed partner qualifies for maternity allowance then he could qualify for shared maternity pay and leave—although his partner would have to stop receiving the maternity allowance and wouldn’t qualify for the shared parental leave.

In these circumstances Ms Brabin says “This places the burden of childcare on the mum, denying fathers financial support and bonding time with the child.”

The majority of self-employed people are men

Around 33% of all self-employed people were women as of June to August 2017. Women represent the majority of part-time, self-employed workers (59%) and 22% of all full-time self-employed workers over the same time period.

There are around 4.9 million self-employed workers in the UK and the majority work full-time.