What was claimed

Maths and science has fallen to a record low in Scottish schools

Our verdict

Scotland’s maths and science ranking has fallen to a record low in international league tables but attainment in national qualifications has risen

Maths and science has fallen to a record low in Scottish schools

Scotland’s maths and science ranking has fallen to a record low in international league tables but attainment in national qualifications has risen

The Scottish Parliament hasn’t debated education for two years.

There have been several education debates.

“Maths and science in schools in Scotland, unlike any other part of the United Kingdom, is going down in the PISA rankings.”

Boris Johnson, 15 January 2020

“Schools in Scotland where, through no fault of the pupils, performance in maths and science is at a record low.”

Boris Johnson, 22 January 2020

“The SNP has not had a debate in its Parliament on education for two years.”

Boris Johnson, 29 January 2020

Boris Johnson is right to say maths and science in schools in Scotland has fallen to a record low in the international PISA rankings, though performance in national exams has improved. It is not the only part of the UK to have received lower scores in science though. He is wrong to say there has not been a debate in Holyrood on education for two years.

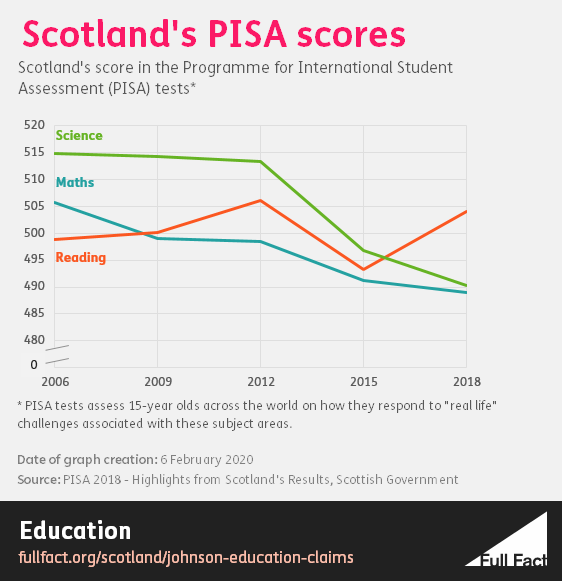

Every three years, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures the performance of 15 and 16 year-olds in maths, science and reading around the world. Scotland’s performance in the maths and science tests fell sharply in 2015 and dipped again in 2018, dropping to a record low for maths and science since the first comparable data in 2006. The score in reading improved.

As we wrote back in 2014, PISA scores from 2000 and 2003 are not comparable because of weaknesses in the data.

It’s worth noting that because PISA scores come with a degree of error, the falls in maths and science between 2015 and 2018 are not statistically significant. That means we don’t know if they reflect an actual drop in attainment or are just a consequence of error.  There is also debate over the extent to which PISA scores reflect the performance of school systems.

There is also debate over the extent to which PISA scores reflect the performance of school systems.

PISA relies on a random sample of pupils, rather than testing all pupils, and as students do not receive individual scores the tests are not “high stakes” — which means they may make less effort. Rather than judging attainment based on the curriculum, PISA tests how pupils respond to “real life” challenges. John Jerrim, professor of education at the UCL Institute of Education, said PISA is “not a good measure of school system quality”.

He noted that Scotland’s declining results coincided with changes to the PISA methodology, including the move to computer-based tests, which he said leads to the question of whether their results are “being driven by a genuine change, or a change of method (or a mix of both).”

The National Foundation of Educational Research (NFER) administers the PISA tests in the UK. A spokesperson said PISA “provides a snapshot of performance”.

“The scores are affected by the cumulative impact of a wide range of educational and other factors, and so provides one useful measure of the health of an education system—but one which should be considered alongside a range of other evidence.”

NFER added that there is evidence the move to being computer-based in 2015 may have negatively affected science scores, but said the downward trend has continued since then in many countries including Scotland, which “suggests a decline in performance”—but added Scotland’s decline between 2015 and 2018 “was not statistically significant”.

Mr Johnson also said Scotland was the only part of the UK to fall down the PISA rankings in maths and science. This is not completely correct. In science, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all received scores that were “significantly lower” in 2018 than their 2006 results. In maths, Scotland was the only country that has received lower scores over the last few years—England and Wales have received higher scores, while Northern Ireland has stayed about level.

National tests

There are other ways to judge Scottish student’s performance in maths and science.

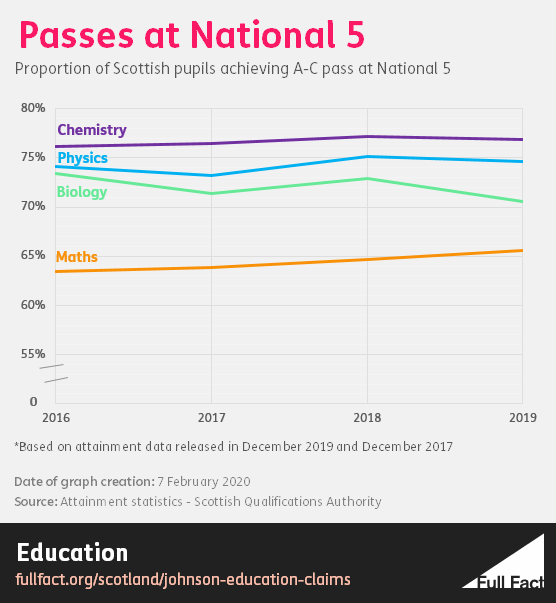

Most pupils in Scotland study National 5 qualifications at 15—the age covered by the PISA tests. Analysis of results in biology, chemistry, maths and physics shows performance is higher than in 2016, both for pupils achieving a pass at A-C and reaching the top grade A.

The only exception is biology, where overall pass rates have fallen despite the proportion achieving an A remaining slightly higher than in 2016.

In Higher and Advanced Higher exams, pass rates and top grades have declined in these subjects since 2016 but remain higher than they were in 2014 for every measure except pass rates in Higher chemistry.

In Higher and Advanced Higher exams, pass rates and top grades have declined in these subjects since 2016 but remain higher than they were in 2014 for every measure except pass rates in Higher chemistry.

By this measure, it doesn’t appear that performance in maths and science is at a record low.

Mr Johnson also claimed that there has not been an education debate in the Scottish Government in two years. However, a search of the government’s debates shows that, since 29 January 2018, there have been six debates on motions about schools, two members’ business debates and four statements by ministers followed by questions.

Topics covered have included subject choice, music tuition, reforms, Catholic schools and autistic children’s experiences of school.

Full Fact contacted Downing Street to ask for clarification on whether Mr Johnson was referring to a specific debate, but did not receive a response.

Full Fact fights for good, reliable information in the media, online, and in politics.

Bad information ruins lives. It promotes hate, damages people’s health, and hurts democracy. You deserve better.