BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time this week was in Chesterfield. On the panel were chief secretary to the treasury and former justice secretary Elizabeth Truss MP, shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry MP, Liberal Democrat leader Vince Cable MP, Guardian columnist Nesrine Malik and LBC presenter Iain Dale. We factchecked claims on the net migration target, stop and search and the drug trade.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“[The Home Office] set the tone which was this, we have to cut immigration down to tens of thousands. They knew they weren’t going to be able to do that, because it was free for people to move about from Europe, so the only way that they could cut back on immigration was [to cut] people who came from outside of Europe."

Emily Thornberry MP, 19 April 2018

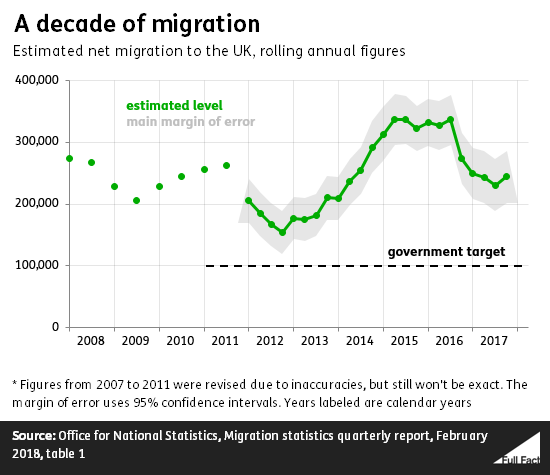

It’s correct that governments since 2010 have set a target to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands, and this target has never been met. Net migration actually rose to more than three times the target at one point and latest figures for the 12 months to September 2017 estimate it at 244,000.

Net migration is the difference between the number of people immigrating to the UK in a year and the number of people emigrating abroad.

In order to meet the target the government would have had to reduce non-EU immigration heavily, because it can’t control the scale of EU (including British) immigration to the UK due to the EU’s rules on free movement. It made some early progress towards this in 2012 and 2013, but the numbers have risen back to roughly 2010 levels again.

So even without any EU net migration, the target would only have been met in parts of 2012 and 2013.

The government actually looked unlikely to meet the target as early as 2011, when its own impact assessments of its policies suggested reductions to non-EU immigration wouldn’t be enough to meet the target. The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford said at the time that “current policies can be expected to deliver about half the reduction in non-EU net migration required to achieve the tens of thousands target by 2015”—though it stressed there was a great deal of uncertainty to all of the estimates.

“Only 8% of stop and searches are knife crime related, the overwhelming majority are drug-related.”

Iain Dale, 19 April 2018

This claim is actually just referring to London. In the first three months of 2018, about 9% of stop and searches resulting in a “positive outcome” were for “weapons, points and blades. That’s according to Metropolitan Police figures (which excludes the City of London).

A positive outcome is where action is taken against people who’ve been stopped and searched, like arrests or warnings. The Met Police told us that “weapons, points and blades” included all offensive weapons except firearms, but including things like acid.

By comparison, 60% of stop and searches with a positive outcome were drug-related.

We don’t have the same figures for England and Wales, but we do know that around 14% of searches that result in arrest involve offensive weapons, not including firearms. Just over half are for drugs. Given that these figures are only for arrests, we might expect weapons to account for a greater proportion of cases than in the London figures.

But if you want to find out how effective stop and search is at rooting out weapons, it’s more useful to compare the total number of searches for weapons and the number of positive outcomes.

In the first three months of this year, there were 5577 searches for weapons, points and blades, and 887 positive outcomes, which will include searches for other things (e.g. drugs) that happen to unearth a weapon.

The latest data for England and Wales covers from April 2016 to March 2017 when there were nearly 33,000 searches for offensive weapons, and about 7,000 arrests (arrests being only one of the positive outcomes). These arrests may also come about from searches for other things.

The England and Wales figures relate to stop and searches made under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 which makes up 99.8% of all stop and searches.

“And what we have seen in the way stop and search is now being used, is it is achieving a higher arrest rate.”

Elizabeth Truss MP, 19 April 2018

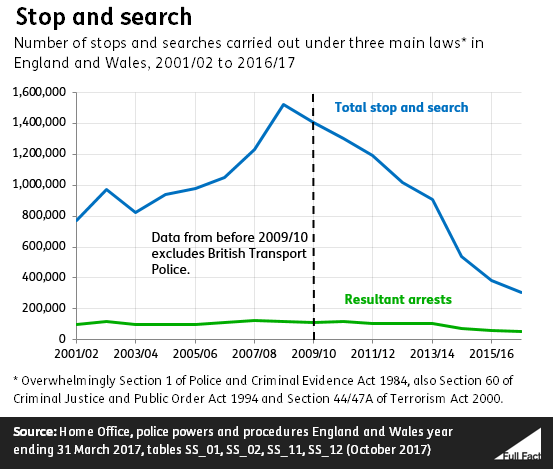

17% of stop and searches in England and Wales resulted in arrests in 2016/17, compared to 8% in 2009/10. There were over 300,000 stop and searches in 2016/17, compared to 1.4 million in 2009/10—meaning the overall number of stop and searches fell by 78%.

While it's tempting to take the higher arrest rate as an indicator of success, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) note that an arrest isn't necessarily a success, nor is a failure to uncover any wrongdoing necessarily a failure.

Offenders could, for instance, be arrested even if they're found to be empty of stolen or prohibited goods because they might react violently to officers or be wanted for another offence. On the flipside, failing to uncover wrongdoing could be regarded as a success if, without the stop and search powers in place, the person under suspicion would otherwise have been arrested unnecessarily.

HMICFRS also reports that “While stop and searches on white people have decreased by 78 percent, stop and searches on people from BAME communities decreased by 69 percent. The decrease for black people was even lower, at 66 percent.” This is based on stop and searches under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, which make up the vast majority of stop and searches.

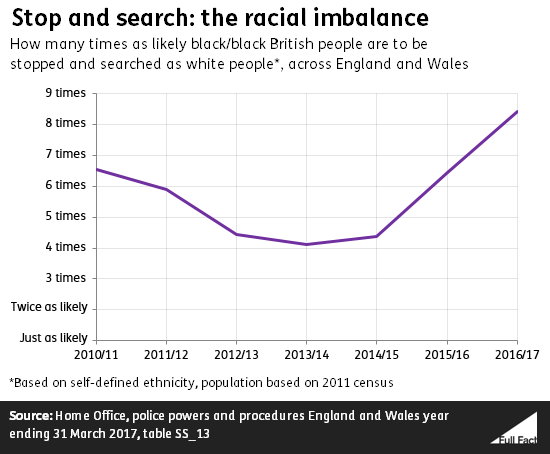

People who self-define as black or black British are the most likely to be stop and searched of any ethnic group—it’s estimated at around 29 per 1,000 in 2016/17. They’re over eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people, and that ratio has been rising in recent years.

HMICFRS said in December 2017 that the rising ethnic disparity in stop and search frequency “has the potential to erode public trust and confidence in the police, particularly amongst black people, despite the reductions in the use of stop and search powers”.

“What is happening is that primary school children are now being used to carry the drugs because they are relatively unobservable.”

Sir Vince Cable MP, 19 April 2018

There is some evidence that children are being used in the drug trade, but we can’t confirm yet if any are as young as Mr Cable claims.

The National Crime Agency (NCA) said in 2017 that “Children as young as 12 are being exploited by gangs to transport drugs into county markets, store and distribute them to customers.”

Speaking to police forces in England and Wales between October 2016 and June 2017, the NCA found that 42% of forces “specifically reported evidence of children ‘running’”—class A drugs and money—for criminal networks between cities and rural towns. The youngest child reported to the NCA was 12 years old, a little older than primary school age.

Media reports suggest that children as young as nine are being used by gangs to distribute drugs—we’re looking into this.

There were over 15,000 people found guilty of an offence relating to the production or supply of drugs in 2016. Around 83% were over the age of 21, 4% were aged between 15 and 17 and 0.1% were between 12 and 14.

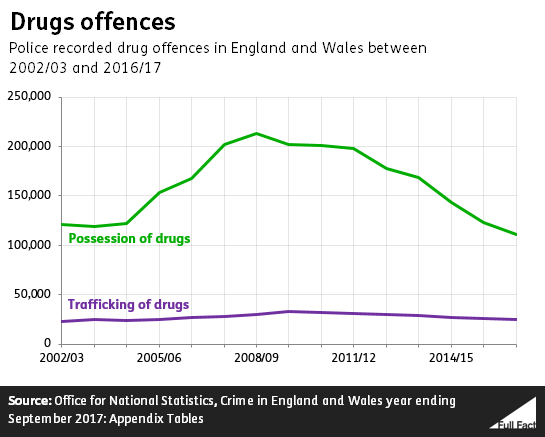

Overall offences recorded by police in England and Wales relating to trafficking drugs have increased slightly in the last year. There were over 25,000 in the 12 months to September 2017, an increase of 1% compared to the year before.

Recent improvements in the way the police record crime may mean that some of this increase is only down to more offences being recorded, rather than more offences actually happening.

Between 80% and 90% of all drug offences relate to possession rather than trafficking of drugs.