Full Fact Report 2025

About this report

Full Fact wants to build a better information environment to restore trust. Our editorial work exposes false and misleading claims and helps promote accurate content, raising standards in public debate and allowing people to make informed choices. Our technology uses generative AI to monitor and detect misinformation at internet scale, allowing small groups of people to find, check and challenge the most harmful claims. Our AI tools have been used in 40 countries worldwide in English, French and Arabic.

This report assesses the state of misinformation in the UK. It explores how political change has created new challenges for those tackling misinformation and disinformation, and examines the tasks facing government, regulators and online platforms as a result.

It follows on from our 2024 report Truth and trust in the age of AI and our 2023 report Informed citizens: Addressing bad information in a healthy democracy. It is the sixth annual report we have been able to produce thanks to the generous support of the Nuffield Foundation.

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social wellbeing. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in education, welfare, and justice. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The Foundation has funded this project, but has no influence on what the report says.

The report and its contents are the responsibility of the Chief Executive. They do not necessarily reflect the views of members of Full Fact’s cross-party Board of Trustees.

We thank our supporters, our trustees and other Full Fact volunteers. Full details of our funding are available on our website.[1]

Executive summary

Full Fact’s 2025 report is being published at a moment of crisis for anyone who cares about verifiable facts—a time of global upheaval, as the second Trump administration rewrites the rules of American engagement and western political norms. Fact checking organisations around the world—which seek to amplify accurate information amidst a deluge of false, misleading or artificially generated junk—are under pressure as never before. Many may not survive.

Fact checking organisations are under pressure as never before.

Many may not survive.

Support fact checking todayBut this is also a time to stand up for our values. Full Fact is an impartial charity, but we will not be impartial about the proposition that facts matter—not only for those of us who work at Full Fact but for us all. The ability to identify, verify, and think critically about information is essential to any meaningful public debate in the UK.

Yet today, the United States is charting a different course. Earlier this year, Vice-President JD Vance came to Europe to talk about the enemy within. He described misinformation as an ugly Soviet era word, and suggested anyone using it wanted to tell others what to think. As we set out at the time,[2] we strongly disagree. Fact checking doesn’t restrict debate; it strengthens it by grounding it in truth. It’s not censorship. It’s more speech, not less—and by that standard, the Vice-President should approve.

We have always been robust defenders of freedom of expression. But we believe free speech is not absolute. It is equally important to protect people from serious harm online. This is a difficult balance to get right, but if everything becomes a matter of opinion—if it is always my facts versus your facts—nothing can ever be questioned or debated effectively.

So we are proud that this report, with a focus on the UK, tackles the real and growing threat of misinformation: false or misleading information—often unintentional—that spreads and can cause real harm. It also touches on disinformation: falsehoods spread deliberately to deceive and damage people, communities, or entire countries.

In the US, pressure from the White House has made even the word misinformation politically charged. In April 2025, the US National Science Foundation abruptly terminated dozens of grants[3] worth many millions of dollars it had previously awarded to researchers studying misinformation, and less contentious phrases like ‘information integrity’ or ‘information credibility’ are now seen as safer options. But debating the language risks missing the real issue: our online information environment is under greater threat than ever before and we must step up our response.

What does this mean in practice? There has been prolonged debate in the UK in recent months about defence spending, and the need to increase it. But defence is not just about bullets and tanks; it’s also about bots and troll farms. We are in a hybrid war, with attacks coming from some hitherto unexpected places, and if we want to protect what we value in our society we need to fight on all fronts. Access to accurate information forms the basis of the robust political debates we need to have. It is not a luxury, it is the foundation of our democracy.

That is why we are so concerned that the large online platforms, which wield so much influence over our daily lives, may see an opportunity to walk away from commitments to make our online world a safer place. We want the UK government and regulators like Ofcom to do more to hold these companies to account, by law if necessary. This is no time for half measures.

This year’s report begins by assessing what our work has revealed about some of the biggest events of the past year—including the UK general election and the riots that took place in the summer of 2024—as well as the daily torrent of misleading and/or synthetic information which appears online as a matter of routine. We also assess the current state of legislation in the UK, covering both online safety and artificial intelligence, and we suggest much-needed improvements.

We examine the policy choices of the online platforms, and urge them to live up to their responsibility to ensure that their users are protected from harm online; the UK regulator, Ofcom, needs to hold them properly to account. Finally, we look at ways in which we have sought to intervene to improve the information environment: we call again on politicians to lead by example and act quickly to correct their mistakes; and we highlight the positive potential of technology in the deployment of our AI tools, which monitor millions of sentences across the internet every day.

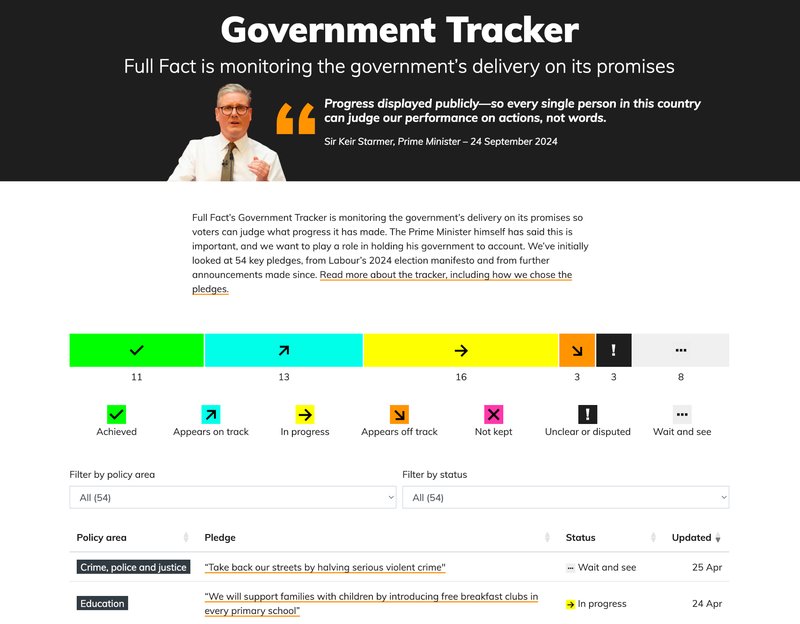

For the first time, our report includes a series of guest essays from experts in various aspects of the work we do, including politicians, academics and activists. We are grateful for their contributions—the opinions they express are theirs, but the responsibility for publication is ours. We are also introducing a rating system to assess:

- the overall state of online misinformation

- the legislative and regulatory response in the UK

- the role of online platforms

- efforts to improve the information environment

We intend to return to these assessments in subsequent reports.

This is a critical year. At a time when the generative AI revolution continues to gather pace, the UK needs to ensure that accurate information is made available in a timely fashion to as many people as possible. The expertise of impartial fact checking organisations is not part of the problem. It is part of the solution.

Our recommendations

To government

- The government must resist pressure from the Trump administration's agenda when drafting new laws on online safety and the regulation of AI. Legislation should focus on protecting UK citizens from harmful content, and giving them access to good information, rather than currying political favour.

- If platforms reduce collaboration with fact checkers, the government should demand clarity: How will they counter misinformation? What data will they share to ensure the public still gets timely, accurate information? There is a need for greater transparency and accountability.

- Misinformation must be treated as a legislative priority, even when it does not meet the threshold of illegal content. The government should revisit proposals for the Online Safety Act, including protections against health misinformation, content neutral solutions, and a statutory media literacy duty for platforms.

To platforms

- Meta should not abandon third-party fact checking globally, and it can still reverse the decision to end its programme in the US. Prioritising policies to counter misinformation, alongside trusted voices, is vital.

- As platforms develop Community Notes models, they must collaborate with high-quality, independent fact checkers—experts who are well funded and can act quickly. Their input is crucial when consensus cannot be reached.

To Ofcom

- The new Online Information Advisory Committee must be proactive, vocal and engaged. It should lead on recommending how protections against misinformation can be enshrined in law.

- Ofcom's media literacy work should be expanded to reflect today's challenges. It should cover all age groups and address emerging threats, especially those driven by generative AI.

Get the facts and support fact checking

Subscribe for email updates.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Online misinformation

The passage of new online safety legislation in the UK has done little to reduce the spread of harmful online misinformation. The riots in the summer of 2024, following the murders of three young girls in Southport, illustrated both the limitations of the Online Safety Act and the task that lies ahead for this new Labour government.

The global context has also become significantly more challenging. One of the most consequential acts affecting the fight against online misinformation was Meta’s decision to terminate its Third-Party Fact Checking programme in the United States. This report is written against the backdrop of that decision. How will fact checkers combat the harmful content they see if the online platforms that dominate its distribution are unwilling to work with them? And what will happen if Meta extends this decision to the United Kingdom and the rest of the world?

We will explore these questions throughout the report, but in this first section we highlight the types of claims our team are seeing on a daily basis. We examine the impact of online misinformation over the past year and outline the landscape in which the new Labour government is operating. These chapters are not an exhaustive list of everything we have seen, but they summarise some of the most pressing issues.

In this section of the report and in the chapters that follow, we seek to answer the question of what can be done to solve the online misinformation crisis. From the government and the online platforms, to healthcare officials and members of the public, we all need to take responsibility for what we’re sharing, hosting and consuming online. Most importantly, we make clear that misinformation needs to be taken seriously, regulated rigorously, and managed proactively to ensure that its real-world consequences are reduced.

Chapter 1: Third-Party Fact Checking with Meta

Introduction

2025 began with one of the world’s largest and most influential companies abruptly changing course. “Fact checkers have just been too politically biased, and have destroyed more trust than they’ve created,”[4] said Meta’s Founder, Chairman and Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg in a 7 January 2025 video announcement that the company would end its Third-Party Fact Checking (TPFC) programme in the United States.

Meta’s accusation of political bias and censorship was deeply disappointing to the fact checking community, and a sudden reversal of years of policy. The evidence provided by Meta to the UK government mere weeks before Mr Zuckerberg’s announcement described its TPFC programme as a “key part of our approach to combating misinformation.”[5] Even after Meta changed course, it continued to highlight its partnership with independent fact checkers outside the United States, for example during the campaign for the 2025 Australian election.[6]

Meta’s U-turn on its collaboration with fact checkers in the United States came at a specific political moment, with the return of President Trump to the White House, and should be seen in that light. For our part, Full Fact wholeheartedly rejects Mr Zuckerberg’s claim of bias. Meta has provided no proof for his claim and we see no reason to overturn a system of independent fact checking that puts reliable, evidence-based verdicts at users’ fingertips.[7]

As members of the European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN) and the International Fact Checking Network (IFCN), our impartiality is rigorously assessed and verified. And, as the code of standards for the EFCSN makes clear, members are “committed to upholding the principles of freedom of expression”[8] and must have a “proven track record of excellence, integrity and accountability”.[9]

Since partnering with Meta in January 2019,[10] Full Fact has checked more than 2,750 cases that include misleading, faked, and potentially harmful posts on Facebook and other platforms. This chapter will outline some of the recurring themes our team has seen over the last 12 months in our TPFC work, in the hope that these lessons may support the work of others in the field. These themes include increases in manipulated/synthetic AI-generated content, a recurrence of old footage and imagery in breaking news contexts to sow confusion and mislead the public, and the impersonation of high-profile people.

We will also explore the implications of Meta’s change of policy on the wider platform sector, and how it may reflect a broader shift in approach to content moderation.

Comment

Khaled Mansour, writer and novelist. Khaled serves on Meta's independent Oversight Board but this article represents his own views.

Over a few horrifying days in March, as many as 1,000 people were killed in Syria’s coastal area, most of them civilians and from the minority Alawite Shiite sect. What the new government in Damascus described as an attempted coup by the remnants of the fallen Assad regime who belonged to this sect, has led to what human rights advocates described as a murderous rampage seemingly by pro-government militias in which hundreds of civilians including women and children were killed after their sectarian identity was identified.

The fledgling government promised a fact-finding commission. This commission will not do justice to its mandate if it does not fully investigate how social media played a pivotal role in this carnage. There is plenty of evidence.

Ahmad Brimo, the founder of Syria Verify, one of this country’s main fact checking operations, says many of the accounts that have been spreading harmful falsehoods were run by individuals or companies and packaged in such a way as to give the impression that they speak on behalf of a certain religious or ethnic group. A widely used technique by sectarian spokespeople relies on the use of fake or manipulated videos and photos—some of which are taken out of context—to convey hateful content in order to incite violence and fuel hostilities across social divisions. Many followers embrace and amplify such content, most believing it to be true.

It has long become evident that social media can turn into a weapon in complex conflicts, like Syria, where sectarian, regional, ethnic and other affiliations are the rallying cry in confrontations to settle what are largely political, economic and social tensions. Social media content is thus often used to mobilise, recruit, fundraise, and organise for violent acts. It is probably worse on Telegram and closed WhatsApp groups compared to more public platforms such as Facebook and X (Twitter). Granted, social media platforms also serve as a tool to build bridges, dismiss rumours and debunk disinformation. They are obviously double-edged swords, but the edge that spills blood is worthy of more attention.

To separate fact from destructive fiction, the root solution is to have discerning and critical users who can sift through a ceaseless flood of images and text. Such users cannot be easily fooled. As angry as they may be at their nemeses, they would not like or share such content. Still, in this day and age, such users seem to be in a minority, especially in the heat of a conflict. This puts an additional burden on social media platforms to tackle incitement to violence and harmful disinformation more effectively, especially during conflicts (and we have a dozen of them from Ukraine to Gaza to the DRC right now). These platforms must moderate content and demote, label or even remove, likely harmful pieces especially when they seem to be going viral or are peddled by suspicious accounts and groups with a sizeable following.

I experienced first-hand how volunteer users in Syria debunk falsehoods or reveal how fake photos and videos left unchecked could lead to more mayhem. But volunteers do not have the same tools or credibility that professional fact checkers do, nor do they come close to having the same impact that the platforms themselves can bring about if they dedicate more resources and effective tools to fight this scourge.

Fact checking is not a binary approach to truth and it cannot easily be substituted by free crowd-sourced labour from amongst the users themselves, as is the case with X’s Community Notes approach, which replaced various safety measures that the platform has gutted after Elon Musk took over. Reporters without Borders[11] claims that X has consequently turned into a “disinformation stronghold”.

This underlines the duty of social media platforms to deploy effective systems to counter misinformation and disinformation. Very large platforms using AI-powered tools need to provide better labelling of potentially harmful content and no longer amplify it with their automatic recommenders. They should stop acting as megaphones for disinformation and borderline content in their ceaseless pursuit of more engagement to push ad revenues up. They are best positioned to uncover deepfakes, manipulated posts, and coordinated campaigns that could lead to real-world harm. In addition to strengthened internal systems, the platforms may then deploy other tools, from crowd-sourced systems to trusted fact checkers.

As I write, I cherish freedom of expression as essential to my creativity. Meanwhile, as an aid worker who witnessed conflicts from Afghanistan to the Sudan and in between for many years, I believe there is a strong need for information integrity and credible sourcing to avoid causing more harm and deepening animosities. Misinformation, disinformation and hate speech—including dehumanisation—can very much kill as we have seen in Rwanda, Myanmar and now in Syria.

Fact checking is not a panacea against disinformation. It must be coupled with internal algorithms that are effective at scale, while public interest organisations work more intensively on equipping users from an early age to consume information critically. Ultimately, when bad information floods a community it very much undermines people’s trust in each other and in public institutions. This erodes the very foundations for which freedom of expression is such a prized right.

Key misinformation themes identified through our work with Meta’s Third-Party Fact Checking Programme over the last year

Increase in manipulated synthetic (AI) content

Over the last year, much of our work with Meta’s TPFC programme has focused on combatting misinformation during high-stakes, global events such as the Russia-Ukraine war, the conflict in the Middle East, and the LA wildfires in early 2025. As events unfolded across media outlets and social media platforms in real time, some users inadvertently shared misinformation, some of which was AI-generated content. Others spread deliberate disinformation in order to sow confusion.

AI-generated imagery, shared as if it is real, can gradually erode trust in information online. This is why our work in fact checking online claims, even those that seem egregiously or obviously false, is crucial to maintaining the integrity of the online information environment.

A few examples to show what we mean:

- An image depicting a bearded man looking up fearfully from an underground passage. This was shared more than a thousand times on social media after Syria’s former President Bashar al-Assad was ousted, as Syrian rebels seized the capital Damascus unopposed in December 2024.[12] According to our research, it is not a real photo, but comes from an unrelated video uploaded to TikTok and created using AI.

- An image we identified in October 2024 appeared to show four Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers with their hands behind their backs, supposedly captured in southern Lebanon. This image was almost certainly AI-generated, with discrepancies such as unnaturally long feet, a rifle that appeared to have barrels at either end, and garbled text on the soldiers' backs. Full Fact found no credible, recent reports of soldiers from the IDF being captured by Hezbollah in southern Lebanon at the time.[13]

- During the LA wildfires, fake pictures of the landmark Hollywood sign on fire began to circulate online after the news that the fire had extended into the hills around it.[14] Although the Hollywood Sign Trust confirmed on Instagram that the sign “continues to stand tall” and did not catch fire, this didn’t stop the misleading images from being shared nearly 3,000 times.

- An uncropped version of one of the images showing the Hollywood sign engulfed in flames included the watermark for ‘Grok’, the generative AI chatbot created by Elon Musk’s startup xAI, indicating it was synthetically produced.[15] At a time when people are being asked to evacuate, accurate information about the spread of wildfires plays an important role in ensuring compliance with evacuation orders. Inaccurate information can cause confusion or delay.

- Other examples of AI-generated misinformation during the LA wildfires came in the form of images of ‘miracle houses’ that were supposedly unaffected by the fires surrounding them. One image of a blue-roofed house that apparently survived the fires also featured the Grok watermark, and another—upon a reverse image search—said it was “Made with Google AI” in the ‘About this image’ section of its metadata, suggesting it was either modified with or created by Google Artificial Intelligence tools.[16]

Individual examples can appear to be of limited significance. But the scale of deception on the internet is staggering, and the need to respond is clear. Full Fact has previously published guidance on how to spot AI-generated content, including tips such as being vigilant about how realistic a scenario might be, looking for inconsistencies within the image, or even doing a reverse image search to check whether the image has appeared elsewhere online.[17]

Re-framing and re-occurence of old footage in new (false) contexts, particularly when there’s breaking news

Another popular tactic is the republication of old footage or imagery in a new context, with accompanying posts or descriptions that imply it is taken from a current event. When authentic footage from previous events is repurposed in this way, it can cause confusion and divert the public’s attention from accurate, real-time updates from reliable sources.

- During the UK riots in the summer of 2024, a screenshot of a TikTok video that falsely claimed to show Hindu and Sikh protesters, marching against illegal immigration, was actually footage from a Hindu religious festival procession through London.[18]

- A video of missiles hitting ships, shared with captions that could be interpreted to mean it depicted real missile attacks in the Red Sea, was actually from the military simulation video game Arma 3.[19]

- A video circulated on Facebook in October 2024 with the caption “Massive explosion reportedly at the Mossad headquarters in Tel Aviv,” actually dates from 2015, and shows a chemical blast at a warehouse in Tianjin, China.[20]

- A video claiming to show Ukrainian troops surrendering in the Kursk region on 11 March 2025 re-purposed footage from 2022.[21]

- A video showing Ukrainian soldiers faking combat to appear “war torn” in order to receive US funds was actually footage from a music video about the war.[22]

Reframed footage of this kind is designed to mislead people, and it can be convincing because it is “real”—not AI-generated or synthetic. But over the long term, it erodes trust as viewers become rightly concerned that they cannot take anything at face value. That damages trust in media, including citizen journalism in which members of the public capture real footage or imagery of breaking news that traditional media outlets sometimes syndicate or include in their reporting.

Impersonation of public figures

Deepfake technology is becoming more sophisticated and more dangerous. With easy-to-use tools, anyone can now edit video and audio to produce convincing impersonations of public figures, resulting in a wave of viral fakes designed to provoke, mislead or confuse. Recent examples include:

- A video supposedly showing celebrities, including Scarlett Johansson, Drake and Jerry Seinfeld wearing t-shirts protesting against Kanye West.[23]

- A fake clip of Taylor Swift saying the wildfires in Los Angeles were “divine retribution” for the US funding missiles used in Gaza.[24]

- A video of Donald Trump supposedly calling for a ban on Skittles and Twizzlers because they contain the red food dye carmine.[25]

- A video appearing to feature an audio recording of President Donald Trump criticising Keir Starmer over aid to Ukraine, energy costs and jobs.[26]

These manipulated clips aren’t harmless. They undermine trust in what we see and hear online, and can spark real-world unrest. In some cases, they also damage the reputation and credibility of the person being impersonated.

Dissemination of hoax posts

Despite previous warnings by Full Fact following an initial investigation in 2023, hoax posts continue to inundate community Facebook groups across the UK. These posts typically feature emotive or alarming information to generate attention, such as claims about missing or found elderly people, children, or pets.[27]

Comment

Tony Thompson, Journalist and Fact Checker with Full Fact

Following years of rapid growth, fraud has become by far the most commonly experienced crime in the UK. It currently accounts for 40% of all offences (in England and Wales) but this is most likely a significant underestimate—the Crime Survey for England and Wales estimates only 13% of cases are ever reported.[28]

While murders, muggings and crimes of sexual violence dominate the headlines, you are far more likely to be a victim of fraud than any other crime.[29] More and more people are being forced to contend with a daily onslaught of scam texts, phishing emails, spoofed calls and fake adverts on social media, all designed to separate them from their money.

Little wonder then that Full Fact’s work in the online misinformation space will regularly cross over with this kind of activity. While some people choose to spread misinformation to create mischief or enhance reputations, others do so purely for financial gain.

One clear version of this kind of activity can be seen in posts that make false claims about the availability of discounted items online. For example, we’ve seen posts claiming that major retailers including Amazon,[30] Argos[31] and Lidl[32] are selling off items such as laptops, pressure washers or Smeg kettles for highly discounted prices.

Clicking on the links attached to such posts usually transports users to a website that closely replicates the branding of a legitimate retailer, but those who enter bank or credit card details can have money withdrawn from their accounts, only to find the promised goods never arrive.

We also regularly see hoax posts on Facebook that seek to attract engagement by featuring highly emotive stories of missing dogs,[33] children[34] or elderly relatives, and implore readers to share the appeals as widely as possible. Once a certain level of engagement has been reached, such posts are typically edited into housing scams or pages offering financial deals.

Our research has found that some of those involved in hoax posts make money by directing people to other websites via hidden affiliate links.[35] The final destination of such links may be a legitimate company offering, for example, cashback services. These companies are the victims as they are paying out affiliate fees to scammers who are breaching the terms and conditions of the services they offer.

Because the fraud takes place away from the social media platform itself, it is less likely that such posts will get removed for breaching the terms and conditions of Meta or its competitors.

More recently we have seen a rise in the use of generative AI to create online misinformation across a wide range of platforms.[36] The technology has also been adopted by fraudsters and scam artists who are using it for everything from writing more realistic posts to generating images and videos of false products and services.[37]

A recent spate of false celebrity endorsements of cryptocurrency schemes made extensive use of AI technology to create deepfake videos of public figures, encouraging people to invest.[38]

Though beyond the scope of Full Fact’s own work in misinformation, some of our partners track the same scammers as they target people through private messages, claiming, for example, to be friends or relatives who have lost their phones or passports and require emergency cash in order to be able to return home from holiday.[39]

What can be done? Increasing public awareness of the many ways in which scammers operate would help. As would stricter controls about creating social media accounts.

Facebook is strict about users having only one profile account that is under their real name. In order to get around this many scammers use Facebook pages rather than profiles. Aimed at businesses, Facebook Pages are indistinguishable from personal profiles in many ways. From the scammers point of view, the benefit is that there is no limit to the number of pages an individual may create and that there is no link between a page and the original profile that created it.

The Online Safety Act now requires online services to assess the risk of fraud on their platforms, and remove illegal content when they are told about it.[40] Time will tell how this works in practice.

In November 2023, following a Full Fact investigation into hoax posts, the then government (along with leading social media companies) pledged to take additional action to block and remove fraudulent content from their sites. In March 2025, however, new research by Full Fact found that the kind of hoax posts we had seen in our 2023 investigation were still rife across Facebook.[41] Our research discovered at least 47 communities across the UK had been the victim of nine different hoaxes, including Facebook groups for big cities like Belfast, Edinburgh and Manchester and smaller places like Banbury, Melton Mowbray and Oldham. We wrote to Meta to urge them to take meaningful action against a pernicious problem that continues to spread on its platform[42] and have yet to receive a response.

Among the most recent hoaxes Full Fact identified were four alarmist posts that aimed to scare communities rather than generate empathy: bogus warnings about a “serial killer”,[43] a man who’d supposedly murdered two police officers,[44] an alleged knife attacker,[45] and claims that a woman had been found stabbed by a local canal.[46]

These hoax posts risk undermining genuine appeals and authentic warnings from well meaning community members in these groups, and render these environments useless as avenues for meaningful local communication.

We’ve previously issued guidance on how to spot a hoax in local Facebook groups online, including disabled comments, posts from pages rather than individual profiles, and cultural references outside the UK which might suggest the post was copied from a similar hoax in a different country.[47]

What does the end of Meta’s Third-Party Fact Checking Programme mean for online safety?

Full Fact’s involvement in the Third-Party Fact Checking (TPFC) programme has had a substantial impact on Meta’s ability to protect users from the harms of misinformation and disinformation. By adding crucial context and credible information to thousands of posts, we’ve helped millions better understand what they are reading and seeing.

It’s impossible for us to quantify the exact impact we have had, because we are not given access to Meta’s own data, but we know that our work has helped to reduce the impact of tens of thousands of misleading and potentially harmful posts on Meta platforms over the last six years. We have never had, nor do we seek, the ability to remove information from the internet.

Instead, we try to focus on identifying and addressing the most viral, high-risk forms of misinformation. Our fact checks appear across Meta’s platforms, offering clear evidence-based explanations, annotated with detailed and informative research, so users can make their own decisions about what to believe—without infringing on free speech.

Meta is now following X’s lead and piloting a Community Notes model. We explore the detail in Chapter 8—but, in short, while Community Notes can be part of a wider solution, crowdsourcing opinions and showcasing competing points of view is no substitute for independent, non-partisan fact checking.

Meta’s version of Community Notes may also lack transparency and accountability—it plans to keep contributors anonymous at first.[48] The system prioritises consensus over factual accuracy, meaning that even if a post is clearly harmful or misleading, it may remain visible in news feeds without consequences.[49]

In the absence of a structured partnership that enables fast, independent fact checks, Meta’s version of Community Notes is likely to fall short. Research by Spanish fact checkers Maldita shows that on X, fact checking organisations are the third most cited source in Community Notes,[50] indicating that users still rely on them to challenge misinformation, and that their work remains a trusted part of content moderation.

Meta’s changes signal a broader shift in content moderation and online safety

Full Fact has often described fact checkers as first responders in the information environment.[51] But as Meta rolls back parts of its TPFC programme, it is also making broader changes that weaken content moderation across its platforms. The company announced plans to drop policies on immigration, gender identity and diversity, and to stop proactively enforcing some policies on harmful content.[52] Meta’s Chief Global Affairs Officer Joel Kaplan confirmed the changes to its hate speech policies were “implemented worldwide immediately.”[53]

That means less oversight of potential misinformation. The Centre for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) argues that these changes “could mean lots more harmful content circulating on Meta platforms.” CCDH’s research says in 2024 over 97% of Meta’s enforcement actions—accounting for nearly 277 million pieces of content—were proactive, leading to fears that ending this approach will undermine online safety.[54]

Elsewhere, other platforms have backed away from strong governing frameworks that protect users from misinformation online, just as they were being absorbed in EU legislation. Google, LinkedIn, and YouTube all withdrew from the European Union’s Code of Practice on Disinformation earlier this year, before it became a binding Code of Conduct.[55] We explore these developments in more detail in Chapter 8, but the implications are clear: less moderation, and less governance, is likely to produce more bad information, and greater harm.

Chapter 2: The 2024 UK riots

Introduction

Widespread disorder broke out in July and August 2024, after three young girls were killed in a horrific knife attack during a Taylor Swift-themed dance class in Southport, north of Liverpool.[56] Calls for protests were amplified by networks of social media influencers that falsely linked illegal immigration to the attacker,[57] who was initially rumoured to have arrived in the UK on a small boat.[58]

The 2024 riots were a clear example of a tragedy on home soil spiralling into serious further harm and civil unrest, fueled in large part by unchecked misinformation. There were other contributory factors, but the rapid dissemination of false information that followed the stabbings helped create a climate that led to violence against mosques, police officers and asylum seekers, and the subsequent arrest of more than 1,200 protesters.[59]

Full Fact was actively involved in fact checking the riots, and ensuring misinformation was flagged and where possible, corrected.[60] We issued more than a dozen fact checks in the days after the stabbings, including a rebuttal of the false image that claimed to show a group of men with “knives and swords” in Stoke, which was actually a still from a video of men celebrating a Yemeni wedding in Birmingham with ceremonial daggers.[61] There was also a fabricated article, purporting to be from the Telegraph, headlined “Keir Starmer considering building ‘emergency detainment camps’ on the Falkland Islands.”[62]

This chapter will focus on what we learned about the spread of online misinformation in the aftermath of the Southport attack. We will consider how false information was disseminated and amplified so rapidly, what else the UK authorities could have done to prevent the escalation in violence, and the inability of online platforms to detect and respond to rapidly emerging harms that needs to be addressed with specific regulation.

Comment

Zoe Manzi and Hannah Rose, Hate and Extremism Analysts at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue

The failure of social media platforms to curb the spread of false narratives in a timely manner, during the riots which took place after the Southport murders last year, may have significantly contributed to the offline violence and disruption which subsequently erupted across the UK.

Immediately after the attack, false claims began to emerge on X (formerly Twitter), TikTok and Facebook, erroneously identifying the perpetrator as a Muslim migrant, “Ali al-Shakati”.[63]

Influential figures with large numbers of followers, including actor-turned-political activist Laurence Fox, further amplified this narrative, using it to call for anti-Muslim action, including the permanent removal of Islam from Great Britain. His post,[64] which amassed over 850,000 views in the first 48 hours after the attack, exemplifies how misinformation is weaponised to incite hate. On X, such posts from paid premium users may be given preference by the platform recommender algorithm, allowing them to reach larger audiences. These findings demand investigation into how Terms of Service are applied to verified users, who should receive enhanced scrutiny during crises to prevent the amplification of harmful disinformation.

Despite police taking the unprecedented step of confirming the alleged perpetrator was a local 17-year-old, misinformation continued to circulate. TikTok’s search recommendations actively surfaced misinformation, suggesting queries like ‘Ali al-Shakati arrested in Southport’ long after the claim had been disproven. Repeating this exercise months later, analysts were still served conspiratorial content and disinformation about the Southport attack through the recommender algorithm.[65] Transparency gaps persist in understanding the role of recommender systems in amplifying harmful content.[66] While the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) legislates limited independent auditing of these systems, the UK’s Online Safety Act (OSA) does not, leaving UK users more vulnerable than our European neighbours.[67]

Permissive platform environments allowed hate speech and conspiracy theories linking immigration to crime to spread and far-right networks to mobilise unhindered. On X, the use of anti-Muslim slurs more than doubled[68] in the ten days following the Southport attack, with over 40,000 mentions. Across British far-right Telegram channels, anti-Muslim hate rose 276% and anti-migrant hate 246%.[69] One X user with 16,000 followers and X premium status posted a protest flyer asserting that ‘children are being sacrificed on the unchecked altar of mass migration.’ These narratives attempt to provide justification for real-world violence, further demonstrating how misinformation and hate speech can have direct offline consequences.

To prevent similar incidents, platforms must develop explicit crisis response protocols to ensure rapid detection and mitigation of harmful misinformation and disinformation.[70] These should include surge capacity during high-risk events, improved coordination with authorities, and a balance between swift action and human rights safeguards. Greater algorithmic transparency and auditing are needed to provide insight into how recommendation systems amplify content during crises,[71] as the lack of independent oversight in the UK leaves users at greater risk of exposure to harmful content. More consistent enforcement of platform policies is also essential to prevent verified accounts and those with large followings from receiving preferential treatment that allows harmful misinformation to spread unchecked. Platforms must improve access to data for researchers and regulators, enabling external monitoring of harmful content trends and the effectiveness of moderation practices. Without meaningful access, addressing online harms remains difficult. Additionally, financial incentives that allow disinformation actors to profit must be addressed. Monetisation policies should be reviewed to prevent bad actors from gaining financial benefits through engagement-driven misinformation.

The speed at which false narratives spread, their amplification by recommendation algorithms, and the delayed response by social media platforms enabled a climate where digital propaganda fuelled real-world violence. The riots which took place following the knife attack in Southport last summer illustrate the urgent need for greater platform accountability and legislative and regulatory clarity. Without enhanced transparency and robust enforcement of platform policies, similar incidents may occur. Addressing these challenges requires ongoing collaboration to ensure that online spaces do not become incubators for violence and social unrest and to mitigate the real-world harms of online disinformation.

Understanding the root problem of how misinformation spreads online is complex and multifaceted, as are the solutions to tackle it. But taking steps to understand it is a significant challenge when the Online Safety Act falls short in regulating misinformation, and therefore fails to create any urgency around complying with the law and improving the information environment.

What we learned about misinformation after the Southport attack

The riots following the Southport stabbings were a stark illustration of how rapidly misinformation can spread and escalate when left unchecked by regulation that is unfit for purpose, and by limited platform oversight.

As violent protests began to escalate, misidentification of the attacker was one of the most common claims Full Fact tracked across social media. Immediately following the stabbings, an allegation began to spread rapidly that the name of the perpetrator was “Ali Al-Shakati”—an allegation that Merseyside Police subsequently confirmed was incorrect.[72] In a February 2025 Select Committee hearing, representatives from TikTok were questioned about including this incorrect name as an automatic suggestion in its “Others Searched For” bar, effectively amplifying this suggestion to users who had not searched for it, and may not have known about it.[73]

TikTok’s Director of Public Policy and Government Affairs, UK and Ireland, Ali Law, conceded that, while the incorrect name was removed entirely as a search result the day after TikTok was notified about it, he would have “liked that to [have happened] faster… absolutely.”[74]

All internet platforms must act more decisively. Last summer’s events followed a pattern we’ve previously observed in which online speculation identifies the wrong person in the aftermath of a major incident,[75] leading to an escalation of violent disorder.[76] It highlighted the danger of reckless accusations, and the potential for innocent individuals to be targeted.

Another major problem was the lack of accurate information to counter these false claims in a timely manner. The response from the police and government as the riots began was too slow, hampered by important contempt of court rules,[77] and that created an information void that added fuel to the fire.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer defended the authorities’ decision to withhold details about the case, despite the rumours swirling on social media. He insisted that to do otherwise would have put the judicial process at risk. In a speech following the Southport attack, Mr Starmer argued: “If this trial had collapsed because I or anyone else had revealed crucial details while the police were investigating while the case was being built, while we were awaiting a verdict, then the vile individual who committed these crimes would have walked away a free man.”[78]

But there is an awareness that some things need to change. The Home Affairs Select Committee, in its inquiry into the police response concluded that “the lack of information published in the wake of the murders of Bebe King, Elsie Dot Stancombe and Alice da Silva Aguiar created a vacuum where misinformation was able to grow, further undermining public confidence. We respect the Crown Prosecution Service’s (CPS’s) commitment to minimising risks to successful prosecutions, but it is clear that neither the law on contempt nor existing CPS guidance for the media and police are fit for the social media age.”[79]

When Baroness Jones, the Minister for Online Safety, and Dan Jarvis MP, the Minister of State for Security, were asked about misinformation around Southport during the Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy’s Inquiry on Defending Democracy, there was little sign of a new government strategy to counter misinformation incidents like these in future.[80] But on the subject of false narratives, Mr Jarvis explained that the government had written to the Law Commission to ask them to expedite their review of rules around contempt of court to ensure misinformation on this scale doesn't happen again.[81]

The riots also demonstrated how existing social tensions can be easily exploited and amplified by misinformation. Fabricated narratives with racial and religious undertones emerged, including the claim that two protesters were “stabbed by Muslims”,[82] which was debunked by Staffordshire Police, who made it clear that “two men involved in the incident were hit with a blunt object that was thrown in the air. No stabbings have been reported to police.”[83]

Further posts included a widely shared call for “no more mosques” which reached more than a million views on X,[84] and incorrectly featured an image of the Brighton Royal Pavilion, implying it was a mosque, to fuel public unrest. A video viewed more than 2.3 million times on X falsely claimed that “an African immigrant stabbed a British police officer” in Manchester. In fact, it was clipped from a longer YouTube video captioned “A bus driver was today the victim of a Acid attack at Piccadilly Bus Station [sic]”.[85]

The widespread use of manipulated media and AI-generated content added complexity to the chaotic scenes on UK streets. AI-generated images, such as a false depiction of police officers kneeling before men in Islamic dress,[86] are increasingly difficult and time-consuming to distinguish from genuine content, slowing the pace of reactive fact checks and supercharging the creation of new “evidence” to embolden existing false narratives.

Once again, platforms could have reacted with more urgency. In April 2025 Meta’s Oversight Board said the company had been too slow to recognise the UK as a high-risk location during the riots. It said three posts on Facebook that advocated violence against immigrants and Muslims should have been taken down at the time “because the likelihood of their inciting additional and imminent unrest and violence was significant”.[87] The Oversight Board said the way Meta enforced its policies in a crisis “revealed inadequacies in the company’s ability to accurately assess visual forms of incitement based on viral disinformation and misinformation”.

The volume of misinformation surrounding the Southport stabbings, and the riots that followed, highlight the need for more robust checks and balances around viral content posted on social media platforms, and stronger cooperation between regulators, fact checkers, the wider media, online platforms and police authorities for addressing crimes spurred on by online falsehoods. This is not about limiting free speech; it is about protecting people from real-world harms.

Why fact checking is important during key information incidents

When fact checkers rate something as false or misleading on Meta, as part of the TPFC programme, their work goes directly to the source of misinformation and empowers users with additional, reliable context to make decisions about what to believe or share. Fact checks that annotate existing posts on social media platforms have been proven to reduce reshares and further amplification of harmful posts. According to Meta’s own research “when a fact-checked label is placed on a post, 95% of people don’t click through to view it”.[88]

During volatile incidents like the 2024 riots, Full Fact is among the few fact checking organisations—and one of just four Meta partners in the UK—that can correct the record, disseminate facts, and counter the spread of baseless rumours directly at the source of the misinformation.[89] While the TPFC programme is far from perfect, this is where its real strength lies.

Context and caveat is also vitally important. We published a detailed explainer article outlining some of the key questions posed by the riots,[90] which was frequently updated in the days which followed. We also distributed our fact checks to leading national media outlets to maximise their visibility and impact when it mattered most. In emergency situations, people deserve access to verifiable facts so they can make up their own minds on issues that matter to them.

Lessons for the government on information disorder

The riots last summer revealed two crucial gaps in legislation. First, the Online Safety Act’s sole focus on illegal content means that very little of the misinformation that circulates online comes under its scope. It is not illegal, for example, to speculate on a false name, even if it causes real harm in a volatile situation. The false communications offence, which is one of the few places where misinformation is enshrined in the OSA, is flawed because it requires proving both intent to cause “physical or psychological harm” and definite prior knowledge that the information sent was false.[91] The case of Bernadette Spofforth, for example, generated media attention. She posted a fake name for the Southport attacker on social media, and was arrested, but ultimately faced no charges.[92]

Second, the Online Safety Act does not include convening powers for Ofcom during major ‘information incidents’, such as terror attacks or the riots following the Southport murders. Clearer protocols are needed to ensure the government, regulators and other trusted voices are able to come together quickly to give accurate information at critical moments.[93] In April 2025, eight months after the riots, Ofcom announced plans for a consultation on a number of measures including the introduction of crisis response protocols for emergency events.[94] We hope that work is conducted at pace.

Private messaging apps make things worse

Public posts on social media may be just the tip of the iceberg. Many industry experts warn that private messaging apps—which are much harder to monitor or regulate—are key tools for spreading misinformation and disinformation, and coordinating harmful or illegal behaviour, in closed-door networks and smaller groups.[95] Telegram channels, for example, played a major role during the 2024 riots,[96] including one linked to the UK chapter of the Active Club Network, a decentralised movement of neo-Nazi white supremacist groups.[97]

A report by the European Fact Checking Standards Network (EFCSN), of which Full Fact is a member, highlights growing concern about Telegram. Nearly 76% of fact checkers across Europe agree it plays a significant role in spreading disinformation. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue previously described Telegram as “a safe space for extremists to coordinate activity and instigate violence”,[98] and while some false claims during the UK riots were not spread with deliberate intent, others clearly were.

So the government needs to be better prepared to tackle similar emergencies in the future. In our sector, that means rethinking how it can ensure that fact checkers are equipped with the right tools, services, and rights to meaningfully tackle misinformation and disinformation at speed and scale.

In Chapter 8, we outline detailed proposals to improve the government’s researcher access scheme. These include secure, real-time access for organisations like Full Fact to platform data that is not always publicly available—something which is essential for stopping the spread of false information without tipping off bad actors.[99] The violence that broke out across the UK last summer clearly showed why fact checkers should have access to the tools they need to debunk the spread of inaccurate and harmful information at speed and scale.

Chapter 3: The 2024 UK election

Introduction

In the run up to the UK general election in July 2024 there was a flurry of warnings that the campaign could be dominated by deepfakes that could undermine democracy. AI-generated, synthetic content weaponised for political means could, commentators warned, distort public debate and influence voting.

These fears were not entirely unfounded: the 2023 Slovakian parliamentary elections showed how the misuse of AI can impact elections, with faked audio featuring one of the party leaders claiming to have rigged the election going viral right before the polls opened.[100]

But for the most part, the UK general election reflected a more nuanced reality: there was a blend of old-fashioned political spin, online misinformation on social media, and low-grade, easily debunked “cheapfakes”. All of them had some impact on the online information environment, from initial campaigning through to polling day but, as Sam Stockwell from the Alan Turing Institute sets out in his essay, deepfakes did not threaten the integrity of the election.

Concern about spin also needs to be put in its proper context. Robust political debate is to be welcomed and expected during an election. But Full Fact was disappointed by the concerted effort by political parties to share exaggerated and often unreliable numerical estimates, which—even after being fact checked—continued to appear in party adverts, social media posts, and high-profile political debates.

In addition, while deepfakes weren’t the central threat that had been anticipated, there were a few examples of apparently synthetic content that couldn’t be verified. Perhaps the most salient example investigated by Full Fact was an audio clip purporting to be the then-shadow health secretary Wes Streeting swearing and claiming he didn’t care about Palestinians being killed in the Israel-Gaza war.[101]

During the campaign, Full Fact carried out more than 450 hours of monitoring, while our AI tools analysed over 136 million words in 142,909 articles, transcripts and social media posts.[102] With the support of 18 additional volunteer fact checkers, we produced approximately 217 verdicts on claims or repeated claims, and published over 150 pieces of website and video content.[103]

This chapter draws on that extensive effort to reflect on the impact of misinformation on the electoral process in the UK, and what must come next to help protect our democratic system.

Parties’ spin and inaccurate figures dominated the election

Contrary to pre-election fears, the course of the 2024 campaign was not ultimately defined by sophisticated deepfakes, but rather by traditional political spin and by misinformation narratives circulating on social media platforms, which were then disseminated by political figures themselves. Familiar tactics, such as the repeated use of exaggerated and often unreliable statistics, were on daily display. And while the rough and tumble of election politics is nothing new, the constant sharing of inaccurate numerical claims, and the refusal to address requests for correction, served only to damage trust in the political process, which was already worryingly low. Four party leaders in the UK signed up to a Full Fact pledge calling for honest campaigning, but the leaders of Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats did not.[104]

The net effect was predictable. According to an Electoral Commission survey after the election, 61% of respondents said they saw misleading or inaccurate information about political parties’ policies during the campaign, and 52% said they saw misleading or inaccurate information about candidates.[105]

Comment

Vijay Rangarajan, Chief Executive, the Electoral Commission

Election campaigns are noisy, colourful, argumentative, sometimes divisive: built around political views and robust debate. The key is that voters hear the different views on offer and can make their choices. But that is why deliberate attempts to mislead voters, or people circulating misleading material, can be a problem: they threaten informed voter choice.

Before last year’s general election, there was a growing concern about the role misinformation and disinformation might play, and whether we were likely to see AI and deepfakes used to try and deceive the public. We, together with others, put in place a number of changes to help mitigate the risk.

The July 2024 campaign was energetic and lively, but when the dust settled after polling day, I think we all saw that there hadn’t been a significant problem… this time.

Voters certainly saw misleading material. After the election, over half of voters surveyed told us they saw misleading or inaccurate information about political parties’ policies and candidates. Around a quarter saw or heard a deepfake photo, video or audio clip about the election. We were made aware of a small number of deepfakes of politicians circulating online during the campaign—reassuringly they tended to be quickly called out for what they were.

In our view, there are two key elements to successfully addressing misinformation and disinformation.

First, voters need to understand how campaigners are trying to influence them during a campaign. This was the first election where we called on anyone using generative AI to clearly label it as such. It was also the first where digital imprints were required on campaign material, which shows everyone who paid to produce it. The Commission has been calling for their introduction for over twenty years, so we were pleased voters could finally see this key piece of information.

Second, it’s crucial to support voters to consider and verify the information they see. At the start of the campaign the Commission published new advice for voters on how to engage confidently with campaign material and think critically about what they saw or heard.[106] We also worked with Shout Out UK and Ofcom to create resources specifically aimed at helping young people to dismiss disinformation.[107]

While the majority of people told us they ignored misleading content, nearly half took action such as fact-checking or reporting the information in some way. So voters value and use services to verify the accuracy of information that bodies such as Full Fact are providing. Impartial, accurate and trusted sources of information are the antidote to efforts to undermine voter confidence and trust.

While the Commission doesn’t have a role in regulating campaign literature, one thing we can do during a campaign is directly and rapidly counter misleading information about the electoral process itself. In the run up to the general election, our voter information hub was viewed 5.1 million times, and we responded to 8,500 queries from members of the public.

Interestingly, younger people were more likely to take action when they came across something they thought was misinformation. We see educating people about democracy as a great tool for countering some of the false narratives we see online about politics and elections.

We are already creating resources that young people and educators can use to explain our democratic processes. Over the next five years, we will scale this up, investing much more into providing young people with the information they need to participate in elections and democracy.

We will also continue to work closely with other organisations, including the UK’s governments, regulators and social media companies, to monitor emerging threats and identify solutions. This includes working to address the concerning trend of candidate abuse and intimidation. After the general election some candidates told us that they felt misinformation that was spread online led to in-person abuse and harassment. This is damaging to the individuals and our democracy and must be tackled—or some will be put off standing as candidates.

We will be paying close attention to this and the information put to voters ahead of the next set of big elections, which are in Scotland and Wales next year. The planning and legislation are already well under way, and we will be monitoring the campaign and experiences of voters.

So there is a lot to do in the coming years to protect our democratic system—including the trust of voters, the enthusiasm of campaigners to share their messages, and the integrity of the voting process. We look forward to doing it with all of you.

One of the most prominent of these claims was first made by then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak the month before the election: that the Labour party’s plan would mean “£2,000 higher taxes for every working family”.[108] This figure, despite being repeatedly shown to be unreliable by fact checkers including Full Fact, was cited repeatedly during the course of the Conservative party’s campaign.

In reality, the claim was rooted in a series of assumptions, including that Labour would fill any budgetary gaps or “black holes” with increased taxes instead of borrowing, and that taxes affect all families across the country equally. Mr Sunak also appeared to attribute the £2,000 figure to “independent Treasury officials”, when in fact it was a Conservative party estimate based on costing Labour’s “unfunded spending commitments”, not all of which were produced by Treasury officials, and several of which we found to be uncertain.[109]

From the opposition arose a similarly dubious claim about mortgage costs under the Conservatives. At a press conference by then-shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves, and in a dossier, the Labour party claimed that “the Conservatives’ plan will mean £4,800 more on your mortgage”.[110]

However, Full Fact found that the £4,800 figure was a speculative estimate that relied on several uncertain assumptions, central among which was that “unfunded promises” under the Conservatives would result in £71 billion worth of extra borrowing.[111]

Both claims were key points of debate during the election, while Full Fact noted that public debate on other issues was limited. In an analysis of a week of broadcasting during the campaign, Full Fact’s AI tools found 6,574 mentions of tax, while other topics paled in comparison, with only 933 mentions of climate change, 922 mentions of housing and 777 mentions of crime.[112]

We also found that misleading political claims spread significantly online, with parties leveraging tactics such as paid display advertising to rapidly disseminate unfounded assertions about opposition policies to a targeted audience.

Days before the election, the Conservatives published widely circulated online advertisements claiming that Labour’s plan to implement a “national ULEZ” (Ultra-Low Emission Zone) would be “coming to a road near you this July”.[113] A search on Facebook’s Ad Library at the time suggested that more than 800 versions of the advert may have been posted.

But there was no specific evidence that Labour was planning to introduce such a scheme, and the party denied any plans to do so. There were also no plans in Labour’s manifesto for a ‘national ULEZ’, and Full Fact was unable to find any other specific information to back up the claim.[114]

It all added up to an election campaign in which disproportionate attention was given to numbers which didn’t add up, or to misleading information masquerading as established fact. Voters, in general, deserved better.

The deepfake threat was overestimated in 2024, but is relevant for future elections

70% of MPs polled in a YouGov survey prior to the 2024 election were concerned about AI-generated content increasing the spread of misinformation and disinformation in the run up to polling day.[115] In the event, their concerns—shared by others—proved to be largely unfounded, but they spoke to widespread unease about the state of online information and the potential for AI technology to deceive and mislead.

Prominent examples were few and far between. An audio clip supposedly of Keir Starmer claiming that he hates Liverpool was widely circulated online, with one post having received over 400,000 views as of 1 July 2024.[116] As with the Wes Streeting audio clip mentioned earlier, we were not able to determine whether the Starmer clip was generated with AI, cleverly edited or was simply the work of a skilled impersonator. But we did not see any evidence to suggest it was real, and we identified versions of the clip that had been circulating since October 2023.

Comment

Sam Stockwell, Alan Turing Institute Centre for Emerging Technology and Security

In 2024, the UK was one of at least 64 countries around the world heading to the polls in what was dubbed "the ultimate election year”.[117] With many of these votes being an attractive target for hostile interference efforts, election security was a particularly high priority.

Yet fast-forward to the end of the year, and it was clear that the negative impact of AI had[118] been[119] overblown[120]—including with the UK election. Firstly, there was no conclusive evidence that such tools had affected election results.[121] One of the main reasons behind this was that there were simply too few viral cases to influence the electorate—with our research identifying just 16 instances in the UK.[122] Given the low volumes coupled with the constant avalanche of information we are exposed to, voters are unlikely to remember these examples. Indeed, a survey from the Alan Turing Institute has shown that only 5.7% of over 1,400 UK respondents could recall seeing a viral political deepfake.[123]

However, we also often tend to “overestimate the change technology brings in the short term and underestimate its long-term effects.”[124] Despite the lack of influence on the election outcome, we did identify worrying signs of second-order damage to the wider democratic system. This included UK users being confused over whether election content they viewed was synthetic or genuine—even on deepfakes which had been verified as such.[125] Not only does this pollute our information ecosystem, but it poses fundamental risks to the ability of users to trust credible sources and complicates fact checking efforts.

Female UK politicians were also targeted by deepfake pornographic smears,[126] with the psychological damage such content caused potentially leading to a ‘chilling effect’ on the willingness of other women to enter politics. Finally, one candidate was even accused of being an AI-generated bot[127]—despite this being debunked.[128] Such rumours reflect a concerning trend where a perceived sense of AI-generated content being everywhere, and difficult to detect, blurs the line between what is real and what is not.[129] In turn, this risks creating a fertile environment for politicians[130] and others[131] to dismiss damaging allegations that may turn out to be credible, or even reshape the truth.

Although deepfakes did not play much of a role in the 2024 UK election, the impact of misleading narratives circulated by political candidates,[132] social media algorithms[133] and ordinary users[134] cannot be neglected. These observations underscore the need to tackle misinformation and disinformation more systematically, as opposed to just narrow election- or AI-based interventions. By targeting different stages of the content’s ‘life cycle’,[135] friction points can be established that make it more challenging for different actors to create or spread deceptive material. With several elections looming in the coming years, complacency cannot creep in. Now is a golden window of opportunity to enhance not only election security, but the very resilience of our democratic system against all forms of mis- and disinformation.

Ultimately the deepfake threat was overshadowed by far more rudimentary forms of digital distortion, such as edited videos designed to misrepresent politicians' statements or events. These "cheapfakes"—less technically advanced pieces of fabricated content that are obviously false—proved effective in misleading voters.

One example: a video of Rachel Reeves pausing for several seconds after being asked about public finances under a Labour government, was clipped and shared with captions like, “Cat got your tongue, Rachel?”—implying that she had been caught off guard or unprepared. However, a review of the full footage revealed technical glitches during the interview that caused a delay between the question and her response.[136]

Another viral image showed Rishi Sunak standing in front of a Morrisons supermarket sign, with part of the logo obscured to spell ‘moron’. This was a composite image of two different photos, edited to make it look like certain letters of the logo were blocked. The picture was seemingly intended to be a joke, but it had also been shared alongside captions which indicated that many people believed it was real.[137]

In last year’s Full Fact report, we wrote about a growing challenge in this space: determining the intent behind AI-generated content. Is it meant as satire or sabotage? Is it a joke gone viral or deliberate disinformation aimed at influencing voters? We are certainly not in the business of fact checking satire, and that blurred line between mischief and manipulation makes it harder to track, label and respond to deceptive material before it spreads.[138]

In any event, the effect of deepfakes in the UK in 2024 was strictly limited, and several factors may have contributed to this. The election was called slightly earlier than many people anticipated, leaving less time for bad actors to prepare. More significantly, the result was never really in doubt. Throughout the campaign, a Labour victory looked like a foregone conclusion—a point even senior Conservatives, like Mel Stride,[139] acknowledged. That sense of inevitability may have reduced the perceived need for dramatic or sophisticated interference.

Safeguarding UK elections from future threats to information integrity

Nevertheless, the threat posed by AI-driven deepfakes is real and evolving, while it could be argued that inaccurate or deceptive political spin, and social media-fuelled misinformation, were both highly effective at distorting public perception over the last year.

Localised misinformation, especially around sensitive global issues, appears to have had a real impact. While Full Fact did not systematically monitor Israel-Gaza-related misinformation at the constituency level, some candidates felt the effects keenly, both online and in person. Labour’s Heather Iqbal, for example, reported being targeted with harassment and abuse, including being labelled a “Zionist and genocide agent”[140]—an accusation which, in her opinion, contributed to her defeat.

Strong political opinions are one thing—but sustained campaigns should be grounded in fact. When political campaigning crosses into intimidation, it shows how targeted, identity-based disinformation can influence outcomes. This suggests future election monitoring may need to go beyond fact checking broad national narratives and dig deeper into the racialised and discriminatory tactics used in specific communities.

In his evidence to the Defending Democracy Inquiry, Dan Jarvis MP, Minister for Security, highlighted the challenges that women and ethnic-minority candidates in particular faced. “It is deeply concerning,” he said, “to think that, in the future, people who are highly qualified to serve in public life might be dissuaded from stepping forward to do so because of the toxic environment that we saw in some places in the general election.”[141]

More work needs to be done to ensure candidates running in future elections are protected from misinformation that targets their identity or political standing. Full Fact continues to call on all candidates to publish honest and transparent election materials that do not intimidate others, spread false narratives, or incite hatred and violence towards groups or political parties. This is essential to preserving the integrity of our elections.

We also urge the government to strengthen safeguards against harmful political deepfakes. Their impact may have been limited in 2024, but that’s no excuse for complacency. Laws must be in place before the next election to tackle misleading synthetic content directly, and we reiterate the calls we developed with Demos on the need for political parties to commit to the responsible use of generative AI.

Public understanding of deepfakes remains shaky. In the Electoral Commission’s post-election survey, nearly one in five respondents (18%) said they didn’t know whether they had encountered a deepfake—highlighting widespread confusion about how to spot this kind of synthetic content.[142]

Sometimes, even real people are mistaken for AI-generated fabrications. Full Fact debunked one such claim involving Reform UK candidate Mark Matlock, whose image on party leaflets led social media users to speculate he might not be a real person, simply because he "looked AI-generated".[143]

A post-election survey from Ofcom echoed this.[144] While 60% of respondents said they had seen content about the election they believed was false or misleading, almost half (46%) weren’t sure whether they’d seen a deepfake at all. That uncertainty only reinforces the need for better public awareness and education on what deepfakes are—and how to identify them.

What needs to change

Clear policies are urgently needed to tackle the growing confusion around deepfakes, and set firm standards for identifying and responding to them. Without action, public understanding won't improve. Full Fact has long called for stronger regulation of deepfakes during election periods—a call that remains unanswered. While in opposition, Labour proposed adding an “offence of creating and sharing political deepfakes” to the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill.[145] It has now faced this threat directly with what appear to be audio deepfakes of Keir Starmer expressing hatred for Liverpool.[146]

The government has already taken steps to criminalise the creation and sharing of sexually explicit deepfakes,[147] which is very welcome. But it’s time to extend those protections to cover political content—before deepfakes undermine trust and do real harm in future elections. With elections approaching in the Welsh and Scottish Parliaments next year, we repeat our call: the UK urgently needs stronger rules to deal with the rising threat of deepfakes in politics.

Chapter 4: Disinformation threats

Introduction

While Full Fact focuses mainly on misinformation, state-sponsored disinformation is also a significant and growing threat, particularly during election campaigns. It is not our core area of expertise, but we monitor developments closely and work with a number of organisations that specialise in it.

As noted in the previous chapter, last year’s UK general election was not affected in significant ways, but disinformation—both state-sponsored and spread by powerful non-state actors—remains a focus of concern across the political spectrum.

In launching a new inquiry—Disinformation diplomacy: how malign actors are seeking to undermine democracy—at the beginning of this year, [148] the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee set out to understand which actors are primarily responsible, and which channels and technologies are being used.

The chair of the committee, Dame Emily Thornberry MP, argued that disinformation campaigns are designed deliberately to sow the seeds of discontent. “They have been weaponised to subvert free and fair elections, to undermine the rules-based international order and to propagate anti-Western narratives. Foreign malign actors have realised the power of the media and social media in supporting their aims and interests.”[149]