The BBC Prime Ministerial Debate: fact checked

On Friday night the final televised debate between Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson, the Labour and Conservative candidates to be the next prime minister, took place on the BBC. We fact checked some of the key claims and major topics from the debate.

The debate was primarily a greatest hits compilation of each leader’s most frequently-repeated lines from the election campaign, almost all of which we have written about before. We’ve rounded these up below, and we’ll add to this with additional fact checks of the few claims we’ve not heard before.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Brexit

Boris Johnson listed some of the suggested benefits of Brexit, including that it would enable us to “create free ports round the country.” As we’ve said before, the EU hasn’t stopped the UK from having free ports. There are around 80 free ports elsewhere in the EU, and the UK itself had them until 2012. However, EU laws do mean their scope is more limited than free ports across the world.

Jeremy Corbyn said that it would take Boris Johnson “seven years to negotiate” a “Canada-style” trade deal. As we wrote during the last debate, the EU’s trade deal with Canada took five years to negotiate, and another two before it was provisionally applied. That doesn’t mean a UK-EU trade deal necessarily would take as long. We’ve not seen any robust predictions for how long a UK-US deal would take, and we don’t yet know exactly what would be on the table during discussions.

Some major EU trade deals (for example with South Korea and Ukraine) have taken longer than seven years to provisionally implement, while others have been quicker than that.

Both leaders promised an imminent end to Brexit under their policies. Mr Johnson repeated that his deal would “get Brexit done”, while Mr Corbyn said of his pledge to renegotiate a deal and hold a referendum within six months “will be the end of the matter”.

As we have said many times, Brexit is a process, not an event. It’s correct that the UK will stop being a member of the EU if Boris Johnson’s deal passes Parliament and the country leaves on January 31 2020, which is just over eight weeks away. But that will not be the end of the Brexit process.

Under Boris Johnson’s deal, negotiations with the EU on a future relationship would then take place during a transition period, during which time the UK will still follow EU rules and pay money into the EU budget. The withdrawal agreement does not by itself secure a trade deal with the EU—that would have to be negotiated during the transition period.

And under Jeremy Corbyn’s proposals, as we wrote the other week, if Leave were to win the referendum on Labour’s renegotiated withdrawal agreement, the UK would again have to finalise its new relationship.

Health and the NHS

Mr Johnson and Mr Corbyn clashed over how many new hospitals the Conservatives have promised. Mr Corbyn said that initially Mr Johnson “announced there was going to be 40 new hospitals, a week later that became 20, a bit later on it became six new hospitals”, which is not quite right: it mixes up an earlier announcement about upgrades to 20 hospitals (about which there was a row over what counted as “new money”) with the subsequent pledge to build 40 new hospitals.

As we have written many, many times, only six hospitals are actually getting money for building work at this point. The remaining 34 will come from up to 38 other hospitals which have received money to plan for building work between 2025 and 2030, but not to actually begin any work. These hospitals are not expected to be delivered until after the next election.

Boris Johnson also mentioned what he called “the biggest cash boost, £34 billion” for the NHS. As we’ve explained before, £34 billion is the spending increase between 2018/19 and 2023/24 without taking inflation into account. In real terms it’s an increase of £20.5 billion. This isn’t the biggest increase ever over five years—the last time there was a larger spending increase on health in England was between 2004/05 and 2009/10.

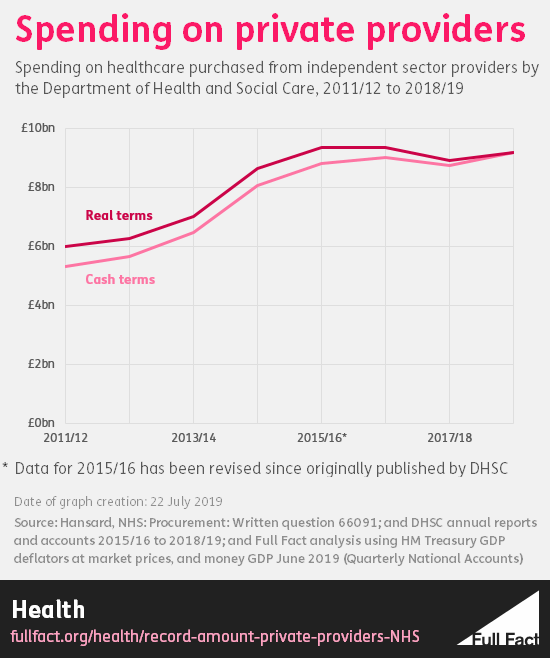

Mr Corbyn also talked about the Health and Social Care Act of 2012, which he said “has led to £10 billion of private sector involvement in the NHS”. As we wrote a few weeks ago, there are a number of different ways you can count up private sector spending in the NHS. Using one commonly used figure, in 2018/19 around £9.2 billion was spent on buying healthcare from independent sector providers by the NHS in England. This has risen in recent years, although it was higher in both 2015/16 and 2016/17.

But this is not all down to the Health and Social Care Act, or the Coalition government: much of this spending began under the previous Labour government. As the Health Foundation and Institute for Fiscal Studies have said, “the role of the private sector... was formalised and expanded in the 2000s”.

The leaders also clashed about whether the NHS is “up for sale” in a prospective US trade deal, which is a complicated question that we wrote about at length here.

The economy and spending

Mr Johnson said that Labour would “put up spending to £1.2 trillion” which would mean “a tax burden of £2,400 per taxpayer”. We wrote about these figures before—both of them come from Conservative party estimates that were made before Labour released their manifesto. The figure of £1.2 trillion was an estimate over five years, not one year, and contained some flawed assumptions.

The figure of £2,400 per taxpayer was based on that sum, but relied on the misleading approach of simply dividing that spending by the number of income tax payers. As we’ve written, this ignores that Labour does not plan to fund its spending pledges through higher income tax for everybody (and even if it did, the cost would fall disproportionately on higher earners).

In his opening statement, Jeremy Corbyn said there are four million children living in poverty. This all depends on where you draw the poverty line, but official figures do suggest around 4.1 million children in the UK live in a household on relative low income. However work by the independent Social Metrics Commission suggests when other living costs are factored in, around 4.6 million could be in poverty.

Jeremy Corbyn said that the UK is the world’s fifth richest country. In terms of total GDP, the UK is the sixth- or ninth-richest, depending on which measure you use. It may be more relevant to look at GDP per person, as Mr Corbyn is making a point about inequality, although this also has drawbacks. On this measure, the UK is 20th or 27th richest.

Police and crime

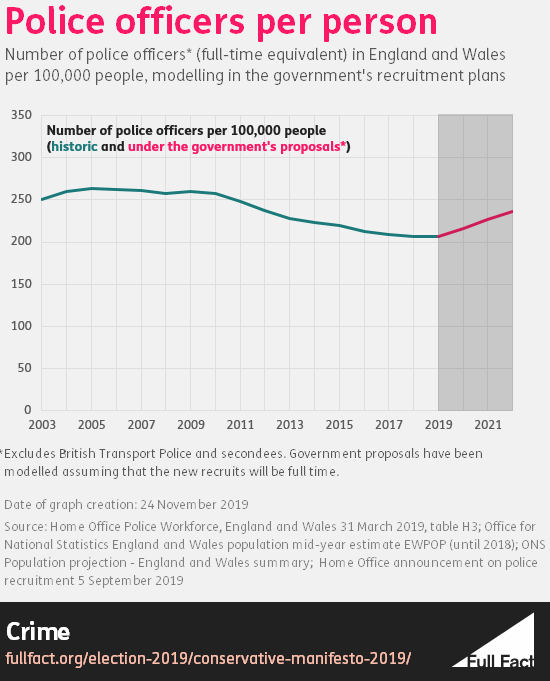

Boris Johnson repeated his party’s policy to put “20,000 more officers on the streets”, while Jeremy Corbyn pointed out the government had “cut the police by such massive numbers”. An increase of 20,000 full-time equivalent officers in England and Wales wouldn’t quite offset the fall of nearly 21,000 officers, or 14%, since 2010.

After accounting for the growth in population, the number of police officers per person has fallen by 19% since 2010. As we wrote a few weeks ago, all else remaining the same, recruiting another 20,000 full-time police officers would leave the number of police officers per person 8% lower than it was in 2010, factoring in projected population increase and the government’s recruitment timetable.

Boris Johnson also criticised Labour’s policy on stop and search, saying that he believed it was an “integral part of fighting crime on our streets”. As we’ve discussed before, data suggests that stop and search is not particularly effective at reducing crime by deterring potential criminals.

There is some slim evidence that it works as an investigatory power for the police (for example police using the powers to search someone and subsequently making an arrest or giving out a warning or penalty notice). There is also evidence from the College of Policing that disproportionate use of stop and search against particular social groups—most notably black and minority ethnic groups and young people—may increase their perception that they are being targeted unfairly.

Later on the debate turned to prisons. Jeremy Corbyn said there were “seriously overcrowded prisons” and added “we have lost prison officers”.

In October 2019, about 56% of prisons in England and Wales were overcrowded. Overcrowding is nothing new—the overall prison population has been above what is considered “uncrowded capacity” almost constantly for decades.

There are around 19,100 ‘front-line’ prison officers (those working at salary band three or four), who are not in management or supporting roles. That number is down from 20,000 in 2010, measuring by ‘full-time equivalent’ roles rather than headcount in all cases.