Boris Johnson's first speech as Prime Minister: factchecked

Boris Johnson made his debut speech as Prime Minister outside Number 10 Downing Street on Wednesday afternoon. We’ve previously factchecked a series of claims Theresa May made in her first speech as Prime Minister, and then factchecked her resignation speech as well.

In the same spirit, we’ve delved into the facts behind Mr Johnson’s first speech—what he got right, what he got wrong, and the context you need to understand the pledges he made.

“My job is to make your street safer and we will begin with another 20,000 police on the streets, and we start recruiting forthwith.”

The number of police officers (full-time equivalent) in England and Wales has fallen by over 20,000 between March 2010 and March 2018. We’ve written more about what’s happened to police numbers over the last few years here.

“My job is to make sure you don’t have to wait three weeks to see your GP”

Boris Johnson talked about ensuring people don’t have to wait three weeks for a GP appointment.

The latest data for England shows that one in ten people wait over three weeks for a GP appointment, although this doesn’t tell us how many of those people did so because they couldn’t get an earlier appointment .

The GP Patient Survey for England tells us more about whether people get appointments when they want, but it’s not detailed enough to say how many have to wait three weeks.

In 2019, 11% of patients said they “never or almost never” speak to their preferred GP when they would like to, with another 41% saying they succeed “some of the time”.

“...and we start work this week with 20 new hospital upgrades and ensuring that the money for the NHS really does get to the front line.”

Mr Johnson committed to this in his speech, but according to the Health Services Journal, the details of exactly which hospitals these will be and how they will be upgraded are unclear.

“My job is to protect you or your parents or grandparents from the fear of having to sell your home to pay for the costs of care.”

At the moment, people needing social care can have it paid for in part or in full by their local council, but usually only if they have wealth below £23,250. The value of your home is included in this ‘wealth’ if you do not receive care at home.

In some cases people who receive care from their council can use a deferred payment scheme to pay for it. Paying for care in a care home can be put off until the point of the person’s death and at this point a person’s home can often be sold to repay the council.

These rules only apply if you receive care from your local council, not if care is purchased privately. We’ve written more about this and previous attempts to change the system here.

Estimates of how many people have to sell their homes to pay for care each year are highly uncertain.

“And so I am announcing now, on the steps of Downing Street, that we will fix the crisis in social care once and for all with a clear plan we have prepared, to give every older person the dignity and security they deserve.”

Between 2010/11 and 2017/18 a £6 billion social care spending gap opened up in England, according to the Health Foundation think tank. It says that without additional government spending there will be a further £2.7 billion gap by 2023/24. The Conservatives promised a green paper on social care during the 2017 election but this has not yet materialised.

We’ve written more about social care here.

“My job is to make sure your kids get a superb education wherever they are in the country, and that is why we have already announced we’re going to level up per-pupil funding in primary and secondary schools.”

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) says that school spending per pupil in England will be held constant in real terms from 2017/18 to 2019/20, and fell by 8% from 2009/10 to 2017/18.

During the Conservative leadership election campaign Mr Johnson initially pledged to ensure per pupil funding was at least £5,000 across England. At the moment the new national funding formula for schools has a £4,800 per pupil minimum, but the IFS says this is “largely advisory and local authorities can effectively ignore it.”

During the campaign he also committed to ensuring fair funding across England, highlighting the differences between the amounts schools in different regions of England receive. The IFS says “policymakers who want to reduce differences in funding between areas should be clear that doing so would almost certainly reduce the extent of extra funding for deprivation and/or London weighting.”

Later in the campaign Mr Johnson pledged £4.6 billion per year for schools by 2022/23. This is just short of the amount the IFS has said it would take to reverse spending reductions since 2009 and protect per pupil funding until 2022/23 (£4.9 billion).

“...with higher wages, a higher living wage, higher productivity, we close the opportunity gap...”

During his speech Mr Johnson seems to have made pledges to see wages, the living wage and productivity all increase. So what’s the situation at the moment?

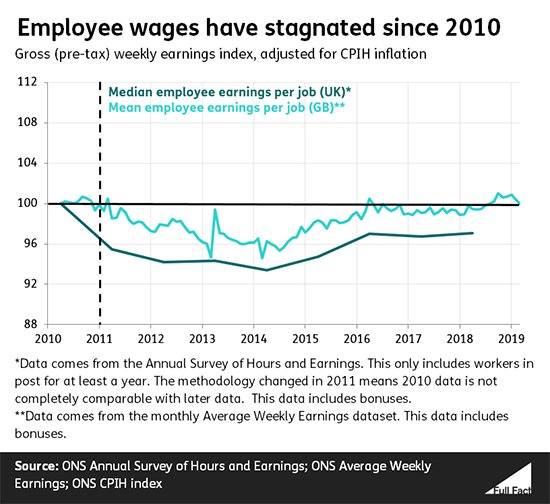

No single data set tells us what’s happening to wages (and we’ve looked at them all in more detail here). Wages are currently growing but are at roughly the level they were back in 2010, following falling wages from 2010 to 2014. Wages are still below their 2008 peak.

There are two different types of living wage: the National Living Wage—which is the minimum wage set out by the government for all workers over the age of 25—and the Real Living Wage—an amount recommended by the Living Wage Foundation for all workers over the age of 18 and voluntarily paid by businesses. The Living Wage Foundation says its recommended hourly pay is based on an estimate of the cost of living.

The Real Living Wage is £9 per hour across the UK and £10.55 per hour in London. The National Living Wage is £8.21 per hour.

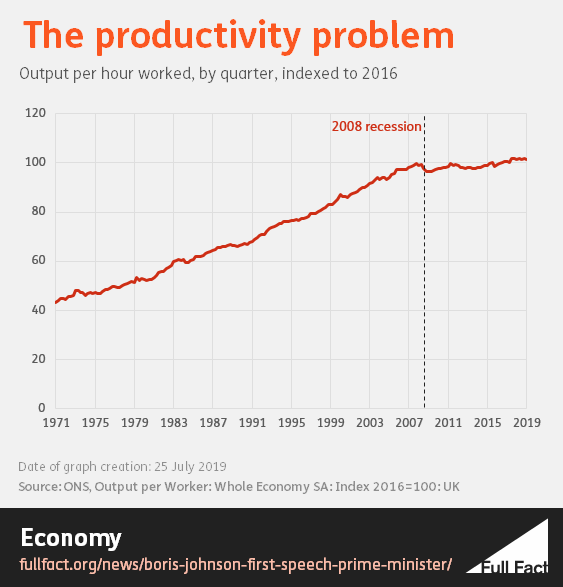

Productivity is a key indicator of an economy’s strength—effectively, it tells you how efficient the economy is at creating value, measured by the amount of economic output per hour worked, or per worker. In the UK this has been almost stagnant over the last 10 years, with a dramatic slowdown in the rate of productivity growth since the 2008 recession.

The reasons for this are the subject of debate: it has been described by the Office for National Statistics as a “productivity puzzle” (and by many others as a “productivity crisis”).

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland - the awesome foursome that are incarnated in that red, white and blue flag...”

The Union Flag (sometimes known as the Union Jack) is made up of three heraldic crosses. The cross of St George (patron saint of England) which is on the English flag and the cross saltire of St Andrew (patron saint of Scotland) which is on the Scottish flag were originally combined in 1606. The cross saltire of St Patrick (patron saint of Ireland) was then added in 1801 after the union between Ireland and the rest of the UK.

The Welsh dragon, depicted on the Welsh flag, doesn’t appear on the Union Flag as when the first version of the flag was made in 1606 the principality of Wales was already united with England.

“The first step is to repeat unequivocally our guarantee to the 3.2 million EU nationals now living and working amongst us...”

This often-quoted figure of 3.2 million EU nationals living in the UK was true in 2015, as it was the latest available during the EU referendum, but it’s now out of date.

The latest data for 2018 shows there were an estimated 3.6 million citizens of other EU countries living in the UK.

“I say next to our friends in Ireland and in Brussels and around the EU—I am convinced we can do a deal without checks at the Irish border because we refuse under any circumstances to have such checks and yet without that anti-democratic backstop and it is of course vital at the same time that we prepare for the remote possibility that Brussels refuses any further to negotiate and we are forced to come out with no deal”

How “remote” this possibility is depends on what it is Mr. Johnson intends to renegotiate. In his speech, he promised “a new deal, a better deal”, but one that would be “without that anti-democratic backstop”.

This suggests that Brussels declining to renegotiate is hardly a remote possibility. The deal negotiated by Theresa May came in two parts: the legally binding Withdrawal Agreement, and the non-binding Political Declaration. The Irish backstop is included in the Withdrawal Agreement; if Mr Johnson wants to remove the backstop, that’s what he will have to renegotiate.

The EU has made it clear that it has no plans to renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement. Senior EU figures such as Donald Tusk, Michel Barnier and Jean-Claude Juncker repeatedly said during the past two years that they will not sign up to any agreement that doesn’t include a guarantee on the Irish border, and that the current Withdrawal Agreement (including the backstop) is not up for renegotiation.

This position, has recently been reiterated by the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Leo Varadkar; in the past few days the position that the Withdrawal Agreement cannot be reopened been restated by figures including deputy EU Commissioner Frans Timmermans and incoming Commission president Ursula von der Leyen.

It is generally accepted that there is more scope for rewriting the accompanying Political Declaration, which lays out the intended direction of talks on the future relationship between the UK and the EU. But that would not remove the backstop.

“Don’t forget that in the event of a no deal outcome we will have that extra lubrication of the £39 billion...”

As part of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated by former-Prime Minister Theresa May, the UK agreed in principle to pay a ‘divorce bill’ to the EU, which was initially valued at £39 billion. This was to cover outstanding commitments like budget contributions up to 2020, pension payments and other outstanding commitments.

But this figure is now out of date. Since the bill was agreed in principle, the UK’s departure from the EU has been delayed.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now estimates the divorce bill after we leave the EU will be £32.8 billion, assuming that the UK leaves on 31 October this year.

That’s because roughly £5 billion is expected to be paid as part of the UK’s normal membership payments to the EU between March and October, and another £1 billion was revised out of the figure before March . So in effect, some of that notional “lubrication” has already been paid and will no longer be available.

The OBR notes that “while this technically reduces the size of the settlement, it does not change the overall amount that the UK transfers to the EU”. That’s because part of the divorce bill was already planned to include UK payments to the EU budget as if it were a member until the end of 2020.

The other question though is whether the UK would be legally obliged to pay any divorce bill upon leaving. We’ve looked at this before and found that… it’s highly uncertain. Experts at UK in a Changing Europe told us in February that, under international law, it’s not clearly set out that the UK has to pay anything once it has left the EU. However, the EU would be within its rights to take the case to the International Court of Justice as the UK has repeatedly committed to paying.

UK in a Changing Europe also told us that policy makers would also have to consider the reputational damage to the UK that could come with not paying.

“...and whatever deal we do, we will prepare this autumn for an economic package to boost British business and to lengthen this country’s lead as the number one destination in this continent for overseas investment.”

The UK had the highest level of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe, according to provisional figures for 2018, at $1.89 billion. That’s according to figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for its member and partner countries.

Foreign direct investment is when a company in one country invests in a company in another, and that investment means they own 10% or larger share.

$1.89 billion is the figure for FDI stock in the UK, which is the accumulated figure including past investments.

When looking at flows (the amount of FDI into the UK in 2018 alone), the UK ranked fourth out of the OECD’s members and partner countries, behind the USA, China and the Netherlands. These figures can vary dramatically year by year.

“But if there is one thing that has really sapped the confidence of business over the last three years it is not the decisions we have taken, it is our refusal to take decisions.”

There are various ways to measure business confidence. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) measure shows business confidence rose following the Brexit vote, but has fallen in the past two years, roughly in line with business confidence across the OECD.

UK in a Changing Europe says business investment held up well following the 2016 EU referendum, but in 2018 it “changed markedly” and began to fall.

Bank of England Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent has said: “A repeated series of cliff-edges, each of which is expected to be decisive but in reality just gives way to the next cliff, is more damaging for investment than if it had been clear at the outset that the process will take time. This doesn’t mean that resolving things soon, by any means necessary, is the better course. Actively choosing the very thing that businesses seem to fear the most is more likely to mean that investment projects that have so far been postponed will instead be cancelled for good.”

“...it is here in Britain that we are using gene therapy for the first time to treat the most common form of blindness.”

In February it was reported that a woman living in Oxford became the first person in the world to have a gene therapy operation to treat age-related macular degeneration. The surgeon who carried out the procedure said “A genetic treatment administered early on to preserve vision in patients who would otherwise lose their sight would be a tremendous breakthrough in ophthalmology and certainly something I hope to see in the near future.”